The Pale Blue Eye

/Speaking of breaking the basic rules of fair play in a whodunit, my first fiction read of 2023 was the historical mystery thriller The Pale Blue Eye, by Louis Bayard. I first heard of this novel late last year when the teaser for the Netflix film adaptation arrived. A lifelong Poe devotee, I was immediately intrigued. I dithered over whether to read the novel as I have had some of my own Poe-related fiction simmering for a few years, but as I don’t have Netflix and the basic premise wouldn’t leave me alone, I decided to go for it.

I read it in just a few days right after the New Year. I’ve been thinking about and reconsidering it ever since.

The film has been out a while now so the broad outlines of the story should be familiar. Retired New York City constable Gus Landor is called one fine autumn day to meet with the commandant of the United States Military Academy at West Point. The commandant, Sylvanus Thayer, tells Landor that one of the Academy’s cadets has been found hanged. Thayer has already ruled out suicide, as after the victim was discovered his body was cut down and his heart cut out. The corpse they removed to the infirmary. The heart has yet to be found. Thayer asks Landor to investigate, both to find the killer and to protect the Academy, which is still new, untested, and the object of suspicion among some citizens of the young republic.

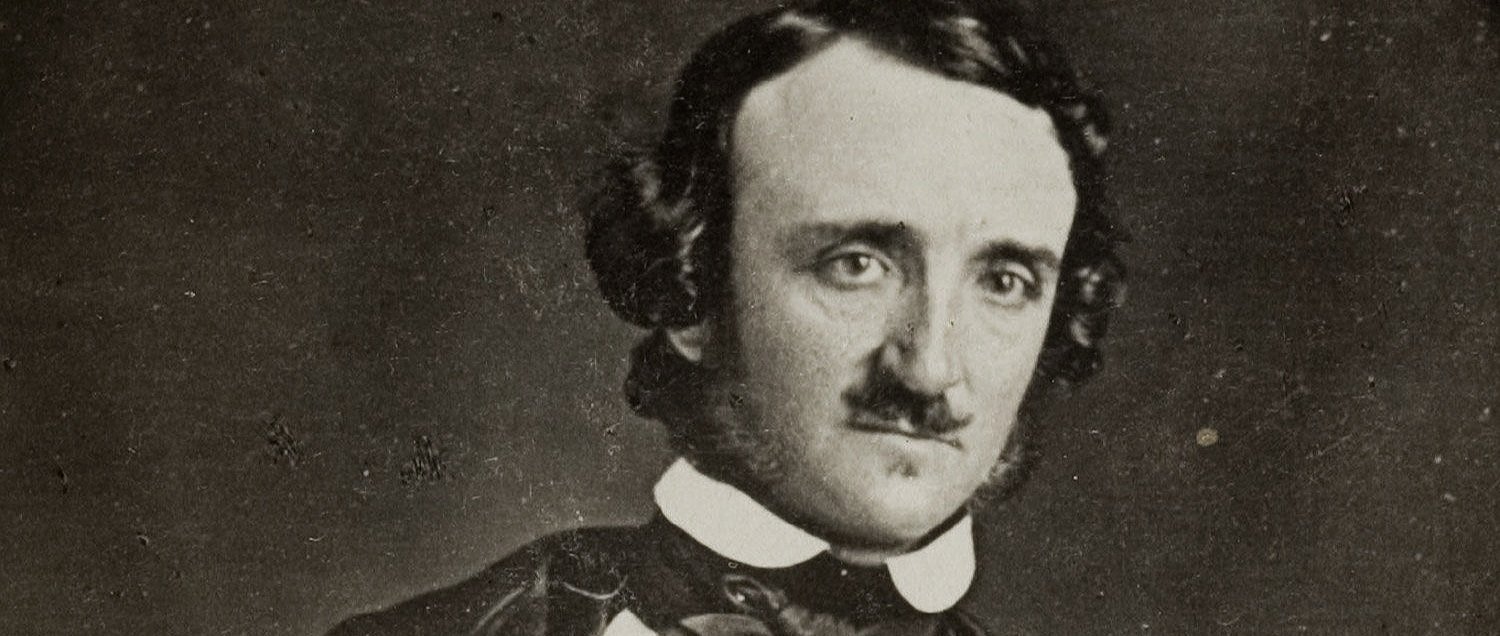

Landor, a consumptive who lives continuously aware of his impending death, agrees to his request with some strict conditions and begins. He questions witnesses, examines the body, searches the barracks, and goes over the grounds of the Academy and the place near the Hudson where the body was found. In the course of his searches he meets a first-year cadet from Virginia, one Edgar A Poe, who offers Landor one sharp bit of advice and disappears. His curiosity piqued, Landor later seeks Poe out at a local tavern and the two strike up an odd partnership built around solving the crime—part crime-fighting duo, part mentor-protégé, part estranged father and orphaned son.

Their partnership is deepened and tested when more cadets are murdered and, even more disturbingly, evidence mounts of some kind of satanic worship extending right into the ranks of the Academy itself.

I don’t want to give much more away, as the unfolding of the investigation, the accumulation of clues, and the working relationship between Landor and Poe is one of The Pale Blue Eye’s great joys. It is also, as it turns out, one of its great frustrations.

Before I get into the one major spoiler, let me praise the two best features of the novel. First, the narrative voice: wry, sardonic, blunt and straightforward but with a finely honed poetic edge, Landor tells his story in such a way that a reader is guaranteed to be hooked. Even when the story’s pacing flagged—as it does in a few places near the middle—I was drawn along by Landor’s narration, which never lost my interest.

The other strength of The Pale Blue Eye is its portrait of young Poe. His semester and a half at West Point is often passed over as a biographical curiosity, but Bayard gives Poe’s time there a central place in his life story and brings this young man, burdened with a hard background and self-sabotaging flaws but buoyed by a tremendous trust in his own gifts, to vibrant life. (Bayard’s interpretation owes too much to Poe biographer Kenneth Silverman, who psychologized and pathologized and autobiographized Poe’s work to death, but that angle is probably only discernible to the enthusiast.) I’ve seen some readers complain that the novel is dull whenever Poe is “offscreen”; I disagree, but it does take on an irresistible energy whenever he appears.

That said, I’ve been reflecting on The Pale Blue Eye ever since I finished it not only because I enjoyed it so much, but because its conclusion, its climactic revelation, was such a cheat: it turns out that the first murdered cadet was killed by Landor himself.

In my post about Glass Onion’s failure to play fair with its audience, I mentioned Ronald Knox’s ten commandments of detective fiction. Knox’s rules had been on my mind because of that movie and I sought out the specific rules again because of this novel. In the case of The Pale Blue Eye, rules seven and eight are broken: “The detective himself must not commit the crime” and “The detective is bound to declare any clues he may discover.”

Given the structure and narration of The Pale Blue Eye, violating the one necessitates violating the other. Landor, having already murdered the first victim when the novel begins, withholds key information—namely, that the cadet had been one of several who had gangraped Landor’s daughter, an act that drove her to suicide. Instead, Landor misleads, telling everyone he meets and us, the readers, directly, that his daughter has left him. This is left as vague as possible: perhaps she ran off with a man, perhaps she died… somehow. Landor’s own tuberculosis offers the reader a red herring by association. His tragic backstory, when it is alluded to, is only a tragic backstory, presented with no apparent connection to the events at the Academy because Landor never gives any specifics regrading what happened to his daughter.

The point is that, until Landor explains precisely what happened in the final pages of the book, the reader could never have guessed at these relationships or events. Even when, about halfway through, I first darkly suspected that Landor was involved in the first murder I told myself it couldn’t be—there was nothing to base that suspicion on. Once Landor confesses to Poe and the reader, it recasts not only the meaning of every event in the book like a good twist should, but the very premise of the story itself. It just doesn’t work. The reader rejects it. The revelation is meant to be a tragic surprise but feels like a betrayal, a betrayal compounded in the last few pages by absurdity as Landor, somehow, narrates throwing himself over the same cliffs where his daughter killed herself.

As I mentioned last time, rules are made to be broken, and I didn’t look up Knox’s rules to hold The Pale Blue Eye accountable for some minor breach of protocol. I despise that use of rules for fiction. (Here’s the worst offender, an utterly arbitrary and stupid measure that many readers take as gospel.) But rules like Knox’s exist for a reason. Think of them less as an imposition of external standards on how to tell a story and more an empirical record of what doesn’t work.

A master, fully cognizant of the rules and of the risks he runs in purposefully breaking one, might get away with it. I’ve mentioned Agatha Christie in this connection before. But more often you will get a novel like this one.

The Pale Blue Eye is a case study in taking such risks and failing. It is brilliantly and often poetically written, full of well-realized characters, spooky gothic atmosphere, evocative and realistic Jacksonian-era period details, and a striking portrait of a real person at a formative moment in his life. But its final twist undermines the entire novel up to that point, making the reader doubt whether it was worth the investigation at all.