I had watched him hunt before, and even taken potshots at squirrels and raccoons, but now he let me carry the guns and taught me in earnest how to bring down small game.

“Your father left you in charge,” he said, “and a man ought to be ready to provide, any time. I’m just here to help.”

He taught me to clean and skin the game on my own and—when my fifth or sixth squirrel dropped out of the trees too torn up to be good for food—a trick of his that I never forgot.

We had just left the porch one morning and by accident flushed some squirrels from my mother’s garden patch, where they had been foraging among the stalks and remains of what we had missed in the picking. They scampered to the fields, up the side of the house, behind the muleshed, and into the shade tree.

My grandfather produced his powder and measured a charge for the rifle. “Let’s get started with these rats here.”

I grounded the shotgun and brought out my powder and pellets.

“Not this time, Georgie. I want to show you something.”

He loaded without looking at the rifle. He regarded the two or three plump squirrels watching us upside down from the shade tree. The tree was a great white oak, older even than the state, five feet wide at the base and better than seventy feet tall. In the high summer we watched the yard like a sundial with the tree as its gnomon.

My grandfather brought the rifle to half-cock and fastened a percussion cap to the nipple. He nodded toward the tree.

“See that fat one there, bout halfway up?” One of the squirrels sat, contented with his distance and sanctuary, dead center in the thickest part of the trunk, about twenty feet up.

“Yes, sir.”

“Watch, now. My granddaddy taught me this.”

He thumbed the hammer to full cock and raised and sighted. The squirrel moved its head minutely, taking in this new intelligence. I heard my grandfather softly breathe out and he fired. The ball struck the trunk of the oak just above the fat squirrel’s head with a sound like a hammer on a loose plank—a miss. And the squirrel flopped backward to the ground anyway.

My grandfather and I stood wreathed in the sulphurous reek of the rifle. The surviving squirrels skittered up and down the tree; a distant dog commenced to barking. I looked at the lifeless squirrel in the yard and up at my grandfather, who grounded the rifle and grinned wide, pressing his tongue against the back of his teeth and chuckling.

At last, he said, “Whew!”

“How—”

My mother burst out of the house, black hair loose, apron in hand.

“God sakes, Daddy!”

“Fixing to rid your okra patch of squirrels, Mary,” he said.

I pointed, awed. “He killed it without even shooting it!”

“If you possess such power why don’t you forebear to shoot at all?”

My grandfather retrieved the squirrel and handed it to me.

“Georgie’s got to learn. He needs a teacher.”

My mother shook her head and strode back into the house. From inside, I heard her declaim to one of my younger brothers about being startled half to death. I laughed and looked at the squirrel. My grandfather grounded the rifle and set to measuring out his powder again.

I turned the squirrel over in my hands. It was still warm and completely unmarked. I looked at its yellow maloccluded teeth and felt an uncanny prickle of fear—I had seen boys with fingers bitten clean through by squirrels and did not want this creature awaking in a fright in my still-tender cotton-raw hands.

“You know what concussion is, Georgie?”

I looked at my grandfather. He stowed the ramrod and waited. “No, sir.”

He balled a fist and struck the open palm of his other hand. “That’s concussion. Shock—the force of smiting something. It’s the concussion, of a kind, that knocks a man down when you strike him. The concussion of your fist on his skull. Now, you knock a man hard enough, the concussion on his skull knocks his brains into his skull. You can do a most powerful lot of harm to a man, you strike him hard enough. You understand?”

“Yes, sir. That’s why you don’t want us fighting? That’s why you say men don’t fight?”

He chuckled. “Naw, men don’t fight each other cause that’s the worse way to go about settling things. But we can talk on that later. Now, what I said about concussing a man’s brains? This bullet—” and he produced one, a .32 caliber lead ball, “—when it strikes a thing, concusses everything around it. You feel a cannonball strike close by, you feel the earth shake. You feel a bullet pass close by your face, you feel it clap the air by your cheek. You hit a tree trunk like that close enough to a squirrel’s skull—not too close, not too far—the concussion knocks its brains and kills it dead just like that. Don’t tear up the meat, don’t hurt the squirrel.”

I marveled over the squirrel. He took it and handed me the rifle. It seemed suddenly like a more powerful instrument than a mere squirrel gun. My grandfather had ennobled it.

“Your turn, Georgie.”

* * * * *

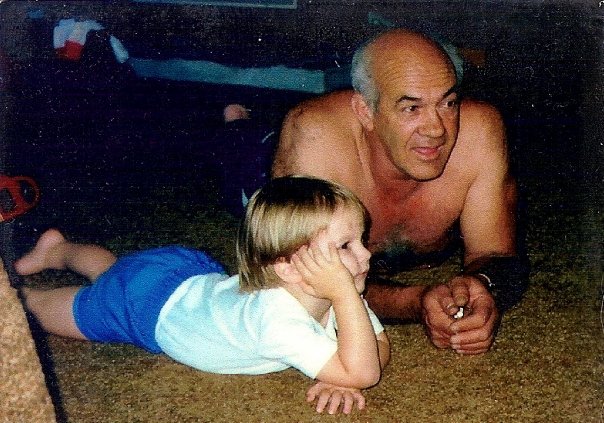

You can read more from Griswoldville here. I hope y’all enjoyed this passage, and will let the memory of my granddad—or men like him—lift and guide you today. We need more people like him.