Elegy for the mass market paperback

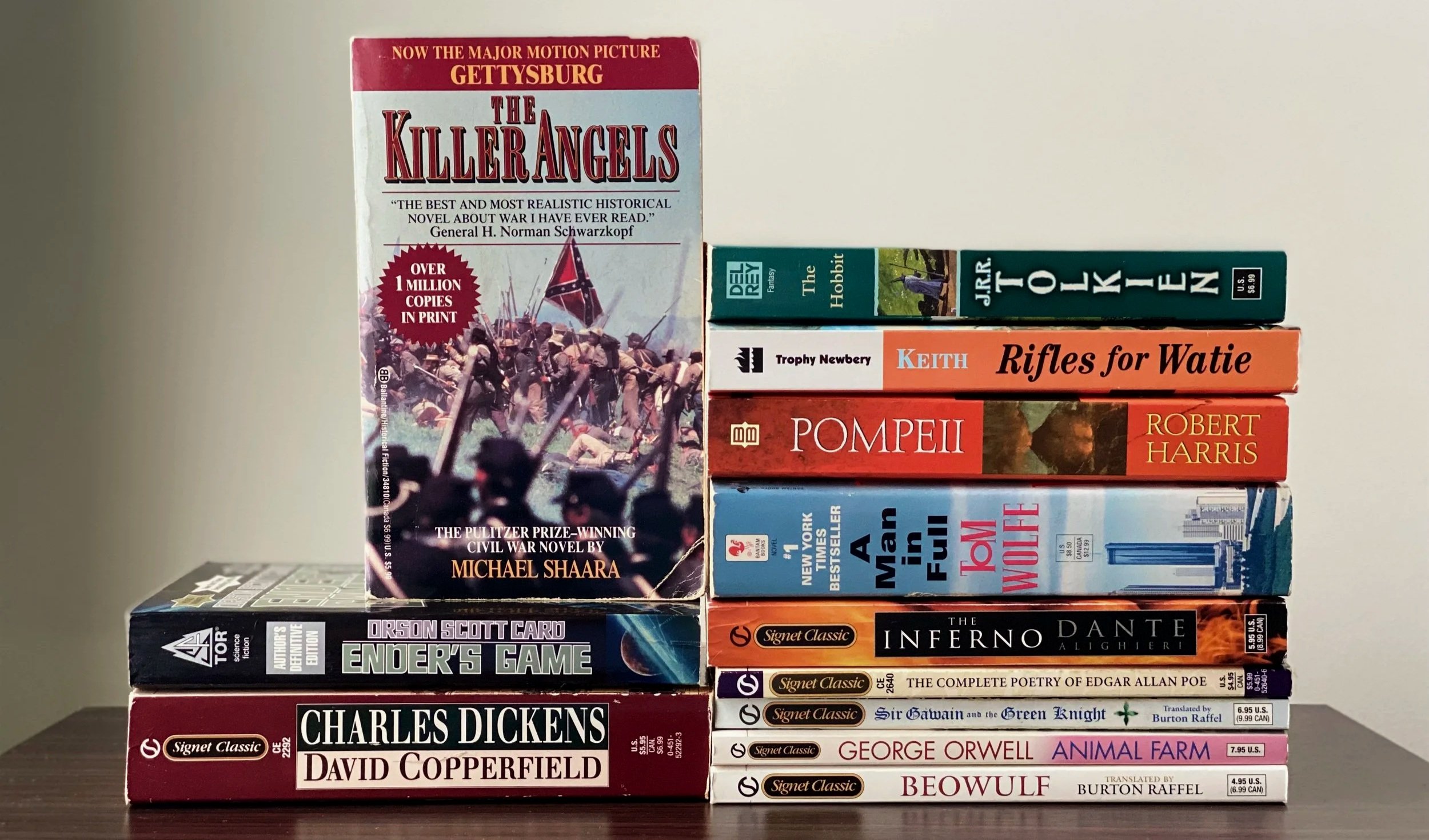

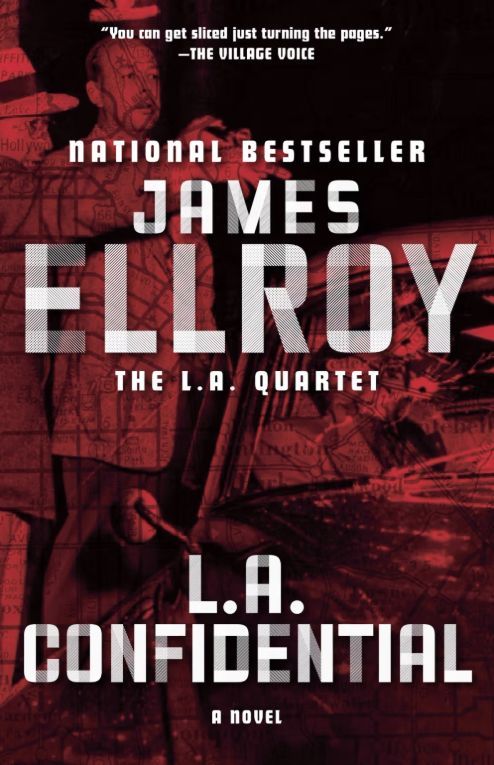

/Some of my oldest and most cherished mass market paperbacks

It’s been a busy week both recovering from last weekend’s ice-storm and two lost days of school and preparing for this weekend’s snow, but not so busy that I didn’t catch a tempest in the Substack teapot: the apparent extinction of the mass market paperback.

In actual fact, Publisher’s Weekly reported last month that the country’s largest book distributor had decided not to bother shipping mass market paperbacks anymore, citing a steep decline in sales over the last few decades and profit margins that were already thin. This will naturally have an effect on how many of them are available and where, but the news was being misunderstood on Substack as either 1) mass market paperbacks will no longer be produced by publishers at all or, more egregiously, 2) paperbacks in general are being discontinued.

In the middle of his hubbub a not insignificant number of voices were raised crying “Good riddance!” Mass market paperbacks, they said, are cheap, badly designed, have small print and margins so narrow your thumbs cover the words, and their spines fall apart almost immediately. A lot of the same people paired their condemnation of the mass market paperback with praise for the hardback.

The mass market paperback may not, in fact, be extinct quite yet, but I can’t tolerate hatred for it.

Let me start with the crassly material. Cheapness is a feature, not a bug. The hardback aficionados seem to forget the kids who want to read but can’t stomach getting only one book for $30 they worked hard for or saved until the day they could visit a good bookstore. The money is just a facilitator, not the point; How much reading will my $20 get me? is the question I asked over and over as a teenager. I still do paperback math in my head—for most modern hardbacks I could have gotten at least six mass market paperbacks back in the day.

As for flimsiness, that’s just the nature of paper and glue. Even the $20—and more and more often $22 or $25—trade paperbacks dominating bookstores today will eventually fall apart from rough use or shoddy binding. Even hardbacks are not bound like they used to be. In my experience, if one takes even a little care of one’s books—not getting them wet, not just throwing them around, not intentionally breaking the spine like a barbarian—they’ll last a long time, and a mass market paperback from a decent publisher will likely be as sturdy as any other size.

And regarding design, a small book will necessarily have smaller print. Adapt. And just how big are your thumbs?

So much for that. Why do I feel so strongly about this?

My affection for the mass market paperback runs deep. I was a country boy without a lot of spare cash for books, so from quite early on, when I got a book, I got a mass market paperback. Many of the books my parents ordered for me at a discount from the God’s World Book Club in elementary school—Rifles for Watie and Across Five Aprils come to mind, as well as things like World’s Strangest Baseball Stories—were mass market paperbacks. I still have many of these.

The Hallmark store on St Simons Island where my mom shopped for gifts and ornaments every summer had an entire wall of these books. It was here that I first found a copy of The Killer Angels, which I knew as the source of Gettysburg, my favorite movie. My parents bought it for me and I just about wore it out reading it in the condo, by the pool, even at supper while a Japanese hibachi chef lit onion volcanoes on fire. Look at the photo at the top of this post—that’s the same copy. Cheap, yes—$5.99 is printed on the spine—but still serviceable.

When I started reading seriously in high school, the mass market paperback made entire literatures available to me for five or six dollars apiece. Signet Classics, which was repackaging their line in nicely designed matte-finish covers as I finished high school and started college, became my go-to. I’d pick up as many as I could with my birthday money during summer trips to St Simons—by this time blessed with a Books-a-Million, which always had a huge inventory of them—or at the Greenville Barnes & Noble when I didn’t have to be in class and had a little money. Burton Raffel’s Beowulf and Sir Gawain, Ovid, Virgil, Boccaccio, Euripides, Malory, Shakespeare, O Henry, David Copperfield, The Song of Roland—just this partial list is an introduction to a whole civilization for about $50.

The most important of all of these was a Signet Classics mass market paperback of Inferno, translated by John Ciardi, which I got sometime in 2001, a quarter century ago. And I can precisely date another important mass market paperback acquisition thanks to Amazon, where my very first order was a copy of All Quiet on the Western Front—in a metallic bronze cover I can still picture—on February 8, 2000.

Again, these are two books that transformed my life and I got both for about $10. (Amazon records the price of my copy of All Quiet as $4.79.) But much more important than the cost effectiveness is what I got out of these books, and the memories I have of them.

I’ve already mentioned a few of these. I also remember reading Inferno on the bus as a high school junior, canto by canto and reading every one of Ciardi’s notes both to uncover more of this amazing book and to block out the chaos around me. I first read Sir Gawain in a single Sunday afternoon as a college freshman, and plowed through The Bonfire of the Vanities over several weeks of lunch in the campus snack shop the same year. I carried my copy of Raffel’s Beowulf in my jacket pocket as I graduated from Clemson sixteen years ago. It was August and it got sweaty but it’s still here on my shelf. And of course there’s the drive to Atlanta in 2000 that I’ve mentioned before, when I read a chapter called “Riddles in the Dark” and realized I loved The Hobbit (purchased at Walmart) and would forever.

The mass market paperback met an important need for me at a specific time. Maturing as a reader, wanting to read a lot, but not having much money or space, and being limited to what was widely available in big bookstores, mass market paperbacks were an intermediate step between the $1 and $2 books in the Dover Thrift catalog I pored over in high school and the Penguin Classics I began collecting in college. Good books, readily available, in workmanlike binding, inexpensive—anything more strikes me as luxury.

I don’t begrudge anyone their hardback library—far from it—but I hate to see the mass market paperback impugned. It’s done humble and honorable service making entertainment and learning available to millions. I’m one of them.

I hope the mass market paperback’s death has been greatly exaggerated and that it will have many years left. But even if not, I’m grateful, and I’ll still enjoy mine.