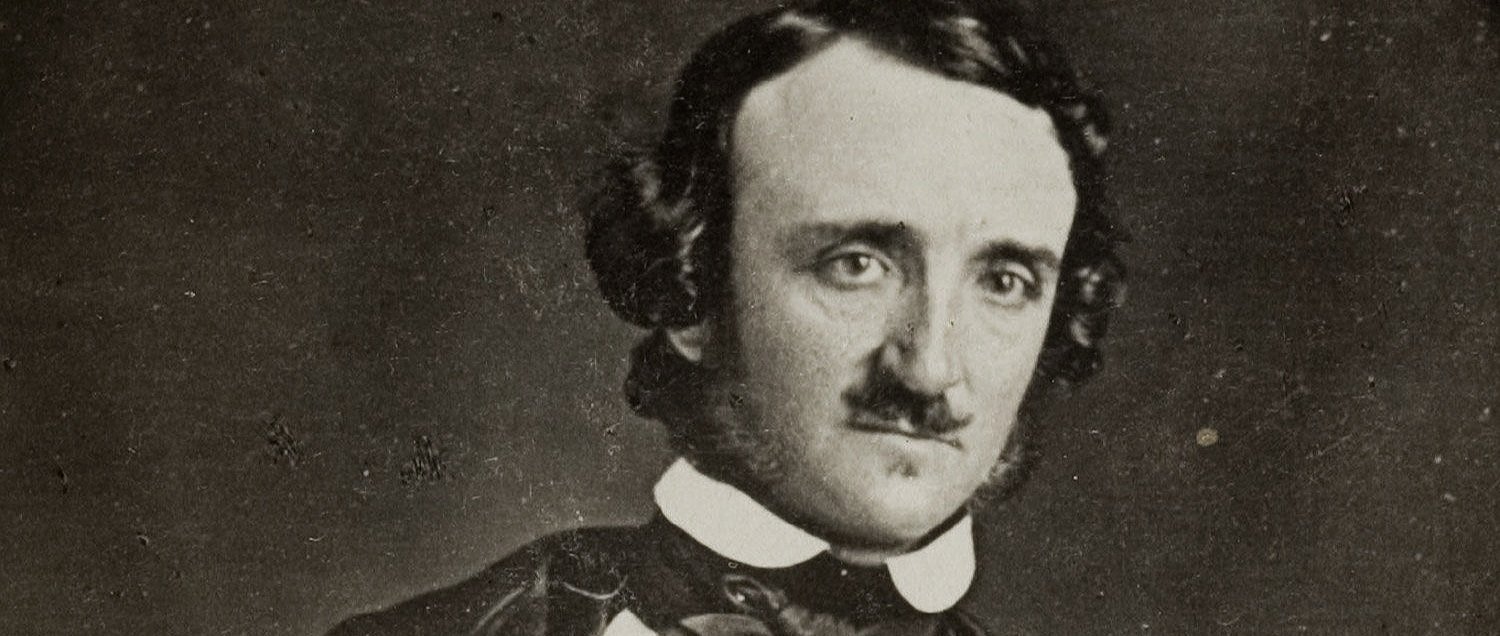

Scare quotes and Poe

/Last night I finished a major new biography of Edgar Allan Poe. It’s by an important Poe scholar—a name I recognized as the editor of my Penguin Classics edition of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym—and published by a university press. It’s excellent—comprehensive, insightful (I had never noticed Poe’s use of chiasmus before), well-researched, and fair. I’m not going to name the book or the author because I don’t want what follows to be construed as an attack on either.

What I want to criticize and wonder about is also not characteristic of the rest of the book, which is what made me notice it in the first place. Think of it as an editorial or rhetorical tic.

Poe might have been born in Boston but he grew up in Virginia, considered himself a Virginian, and nursed recognizably Southern resentments toward northerners, especially New Englanders. He also died sixteen years before the passage of the 13th Amendment, just as the sectional debate was reopened by victory in the Mexican War, leading to failed compromises, mudslinging, vigilantism, and war. Slavery was a fact of life.

The author approaches these topics within the context of Poe’s life with laudable charity and nuance. He takes pains to defend Poe from glib accusations of racism, especially in misinterpretations and misrepresentations of his work—while acknowledging that Poe was still a man of his time.

And yet the book’s own context as the product of a 21st century university press shows through. There is the predictable gesture of capitalizing “black” and the clumsy circumlocution of “enslaved people,” which I complained about back in the spring. Odder, though, are the two passages following, both of which concern Poe’s lifelong best friend John Mackenzie:

Clearly the hard work of the farm was done by enslaved labor. According to tax records, John H. Mackenzie “owned” eleven slaves at this time.

and

John and Louisa’s abundance—in the house, on the 193 acres, even in John’s tobacco warehouses and stables in the city—was made possible by the African Americans whom John “owned”: in 1849, six of them over twelve years old, and another six over sixteen years old.

There’s not really a factual problem here—though I will note that small-scale slaveowners like this very often did do a lot of hard labor and that pointing out the role of slaves in the economy is a truism. My real question: why the scare quotes?

Putting scare quotes around owned suggests some kind of falsehood in the word, that slaveowning was some kind of socially constructed fiction, but John H Mackenzie’s ownership of these slaves as property was an actual and legal fact. That’s the whole problem. Those uncomfortable with slavery—which included far more people for far longer than the abolitionist movement that Poe hated—were uncomfortable with it precisely between of the tension created by treating people as property. Handwaving this tension, “They weren’t really ‘owned’ by someone else,” is insulting. As with the dubious “enslaved people,” treating harsh reality this way undermines one’s own disapproval.

This is a tiny thing in a 700-page book, but a noticeable part of an repeated posture of disapproval that the author does not display elsewhere. Three times the reader is treated to a mention of the Mackenzie’s mantlepiece picture of the Egyptians drowning in the Red Sea with a heavily ironic gloss that someday it would be the slaveowners who would be drowning. The author seems desperate in these passages to let you know he thinks slavery is bad and that it is good that it was abolished. A stunning opinion.

The final odd note comes in the conclusion. Concerning John Mackenzie’s brother Tom, a doctor who championed Poe’s reputation, we read:

Although Tom Mackenzie would have been on the right side of Poe, he was on the wrong side of history.

He served as a surgeon in the Confederate army, you see. “The wrong side of history” is a cringeworthy cliche, and stupid because history doesn’t have sides. This is also an odd thing to throw in at the end of a book about Poe, who famously and vocally denounced the myth of progress.

My own stance on historical writing is that it should be descriptive most of the time—as this book generally is. Opinion and moralizing may have a place occasionally, sure, but not for opinions that are universally approved. In twelve years of teaching college students—who are typically less guarded and studiedly correct in their opinions than professors emeriti—I’ve never had a student even suggest that slavery was okay. Condemning slavery and celebrating slaveowners’ downfall feels performative. Forcefully declaiming obvious, widely shared opinion is not argument, but liturgy. Here the author wants us to know he can recite the creeds of the liberal consensus, too.

Well, perhaps it’s the author. My suspicion, based on the inelegant way these passages fit with the rest of this careful, balanced book, is that these originated as editorial demands. Poe, himself a sometime editor in a time of political polarization, probably would have understood, but not approved.