Kubrick, conspiracism, and what happens when we assume

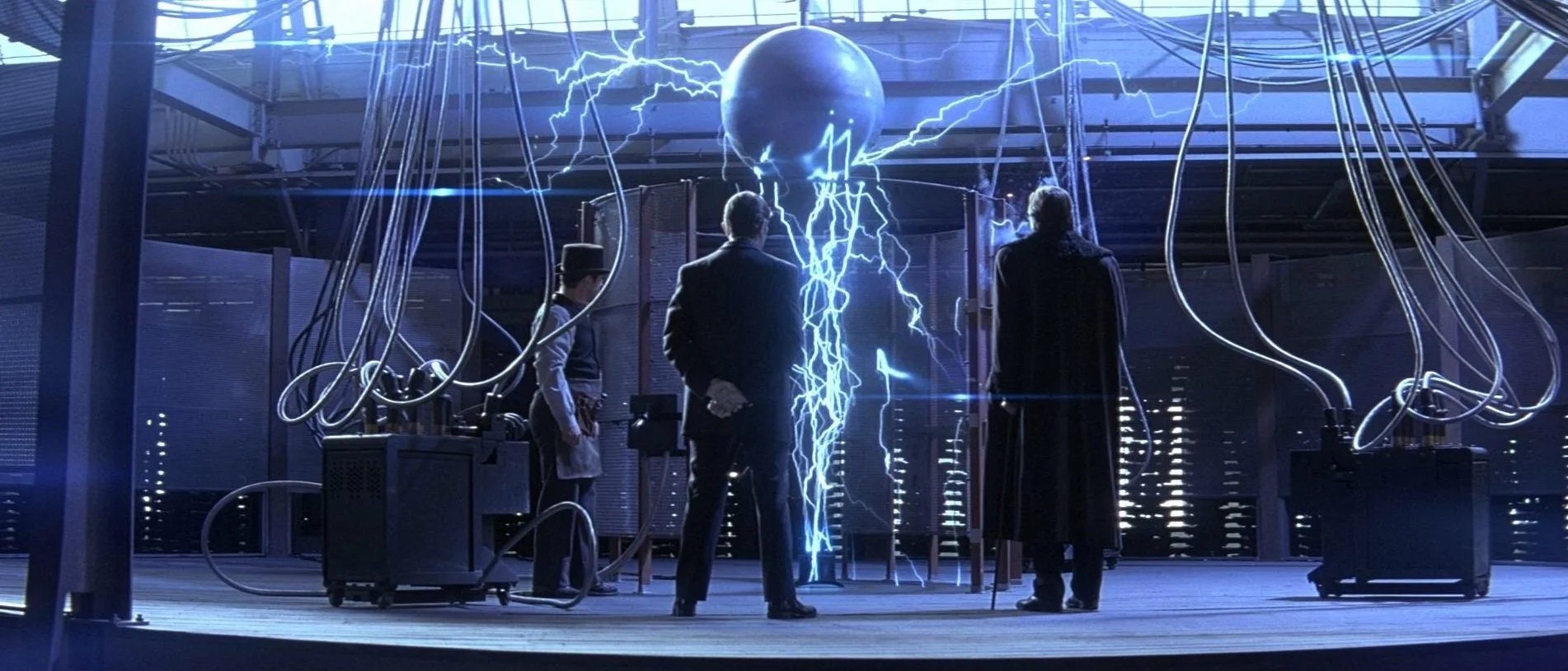

/Stanley Kubrick and Jack Nicholson on set. The miniature hedgemaze in the foreground is an accidental metaphor for the subject of this post.

YouTuber Man Carrying Thing posted a funny and thought-provoking video yesterday concerning a strange emergent pop culture conspiracy theory. Apparently some disappointed fans of “Stranger Things” decided that secret new episodes are on their way, a fact signaled through elaborate visual codes in the final season. (I have no dog in this fight. I saw the first season when it first appeared and have not bothered with any of it since.) These fans have compiled huge numbers of minor details as “evidence” but the date of the supposed release of these surprise episodes has already come and gone. Undeterred, they continue with the predictions.

Jake (Man Carrying Thing) has some thoughtful things to say about this weird story, the most important of which, I think, is the role of bad storytelling in creating false assumptions and the way those assumptions fuel the mad conclusions these fans have come to. In the process he makes a brief comparison to Stanley Kubrick and The Shining, which is what I really want to write about here.

The Shining is the subject of several bizarre but elaborately worked out theories, the two most prominent of which are that the film functions as a hidden-in-plain-sight confession by Kubrick that he faked the moon landings for NASA and that the film has something to say about the fate of American Indians.

The latter is more easily disposed with along the lines Jake uses for some of the “evidence” of the “Stranger Things” theory. Why does the Overlook Hotel have so many Native American decorations? Because that’s what a Western hotel in that era would decorate with. Next question.

The NASA stuff goes deeper, though, and this is where Jake’s comments on the assumptions behind such theories are pertinent. The conspiracy theory interpretations of The Shining lean heavily on several assumptions, the most important of which is that Stanley Kubrick meticulously planned everything about his films down to the last item in every frame. Every detail, the argument goes, is intentional and meaningful, and so the film can and has, as Jake notes, been analyzed frame by frame for “evidence” of these theories. But is this assumption correct?

No. Kubrick was meticulous, yes, but not that meticulous. Or not that kind of meticulous. He was, in fact, too good an artist for that.

I encourage everyone to watch “The Making of The Shining,” a documentary shot by Kubrick’s 17-year old daughter Vivian and included as a special feature on the DVD and Blu-ray. (You can also watch it online here.) While the myth of Kubrick is of the chilly visionary with a perfect movie in his head that he brutally forces into reality, Vivian Kubrick captures her father changing and adapting on the fly, picking the ballroom music at the last minute, discussing the different versions—plural—of the script, and even coming up with the iconic floor-level angle of Jack Nicholson in the storage locker as they’re shooting the scene. She presents us the collaborative mess of filmmaking.

Kubrick knew what he wanted, but he had to work his way there, improvising and improving. This both rubbishes the conspiracist assumption about Kubrick, that The Shining presents some utterly controlled pre-planned message, and also functions as broadly applicable insight into creative work and human nature.

Any good artist in whatever medium will have a clear goal and an idea of how to accomplish it but will also adapt as they go, even the meticulous ones. That’s because every plan is subject to the combined friction of creative work and reality, which test the artist. The later illusion of coherence and completeness is part of the art. A great artist like Kubrick can disguise it well, because thanks to his gifts the final product is better than what he set out to make. But the Duffer brothers? Jake—and audience reaction to the conclusion of “Stranger Things”—suggests otherwise.

As for human nature, conspiracy theories, whose protagonists are often hypercompetent if not omnipotent, fail to take account of the messy, improvisatory quality of reality, especially when they presume to encompass a larger slice of it than that available on a film set. They are, as German scholar Michael Butter puts it in The Nature of Conspiracy Theories, “based on the assumption that human beings can direct the course of history according to their own intentions . . . that history is plannable.” Or in Jake’s words, “So many conspiracy theories would lose their convincing quality if those who believed them acknowledged human fallibility.”

Recognizing this can make us less susceptible to falsehood—because we all know what happens when we assume—and better creators. A strange but heartening intersection.