Goodreads Inferno

/In a longish state-of-the-publishing-world essay on Substack, independent publisher Sam Jordison gives special consideration to the disappearance of the negative book review—the hatchet job—as a symptom of decline. He notes that author and critic DJ Taylor, whose excellent guide to Orwell I wrote about here last year, described the disappearance of “tough-minded” reviews, criticism that “often bordered on outright cruelty,” ten years ago. According to Jordison, the tepid positivity of book review pages has only worsened since then.

What caught my attention was Jordison’s second mention of Taylor’s phrase “outright cruelty,” which Jordison notes we shouldn’t want or need to come back: “We have Goodreads for that.” This observation is glossed with the following footnote:

Goodreads has risen just as professional book pages have declined. The nastiness and ignorance on display there is a reflection of internet culture, and the way everything Jeff Bezos touches is infected with his mean spirit. But I do also wonder if some people think they are restoring some kind of balance?

The nastiness on Goodreads is well known. Goodreads users mob and harrass authors over single lines, engage in character assassination, try to preemptively get books canceled before they’re even published, and even the authors who use Goodreads join in the bad behavior. Imagine the vitriol of Twitter, the politics of Tumblr, and the righteous self-assurance of a school librarian in a Subaru and you have the predominant tone of Goodreads today.

Thanks to the nastiness the profound ignorance on Goodreads is perhaps less visible. But as it happens, it was fresh on my mind because this morning, as I searched for a brand new one-volume edition of The Divine Comedy that I’m about to start reading, I made the mistake of looking at its top review.

According to the user responsible, Dante has written this “OG” “self-insert bible [sic] fanfiction” because he “thanks he is very special” (stated twice), “has a bit of a crush . . . on both Beatrice,” “his dead girlfriend,” and “his poetry man crush” Virgil, and wants “to brag about Italy and dunk on the current pope.” All of this is wrong, for what it’s worth, but here’s the closing paragraph:

TLDR: Do I think everyone should read this? No, it’s veryyyyy dense. But I think everyone should watch a recap video or something to understand a lot of famous literary tropes that become established here.

Read The Divine Comedy for the tropes. Or better yet, “watch a recap video.”

This is a five-star review, by the way.

I wish this were the exception on Goodreads, but it’s not. Here’s a person with the capacity and the patience—perhaps? the review is short on details of anything beyond Inferno—to read the Comedy but who is utterly unprepared to receive and understand it, presumably having lost the good of intellect. This review reads like those parody book review videos that were popular a decade ago, except Thug Notes actually offered legitimate insight as well as laughs.

I have a love-hate relationship with Goodreads. I signed up fourteen years ago and still use it every day. But I can only do so and maintain my sanity by sticking to my tiny corner of online acquaintances and people I actually know and avoiding the hellscape of popular fiction, where the fights that can break out in review comment sections resemble nothing so much as Dante’s damned striving against each other even in death. Finding a legitimate, thoughtful, accurate review is harder than ever. One must dig, sometimes through hundreds of reviews like the one above, to find something helpful. And it’s even harder if you’re interested in older books, for which the temptation toward glibness or snark—omg so outdated! so racist! so sexist!—is for many irresistible.

And, for authors whose books are on Goodreads, it’s hard not to let a latent anxiety build up. Sometimes it feels like, inevitably, it’ll be your turn in the crosshairs.

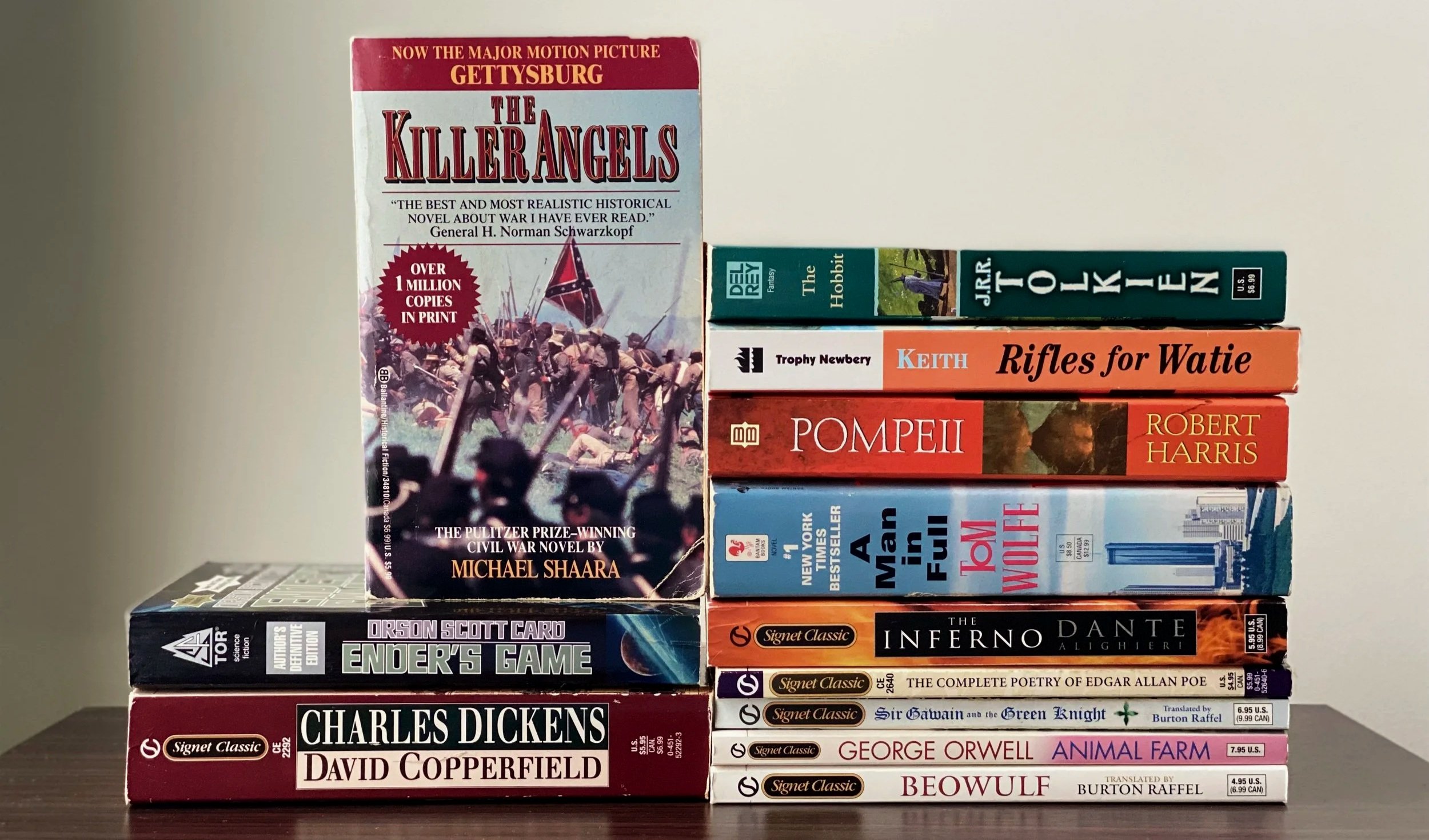

Jordison blames Jeff Bezos, whom he correctly points out—as I just did in my Tech & Culture class last week—started selling books not because he loves them but because they’re easy to catalog and ship. I’m sure that’s a factor, but it’s not sufficient to explain the whole problem. His other culprit, “internet culture,” that broad and protean devil, plays a crucial role as well. Regardless, Jordison ends his essay on a note of hope:

But I don’t counsel despair. Because the truth is that there is still good work being done. There are a few decent book sections left. Writers are producing fine books. Publishers are bringing them into the world. People are reading them.

At least some of those books will endure.

Truly encouraging to remember. But that this must happen despite rather than because of the technologies we’ve created from an ostensible love of books is a judgment on our culture.