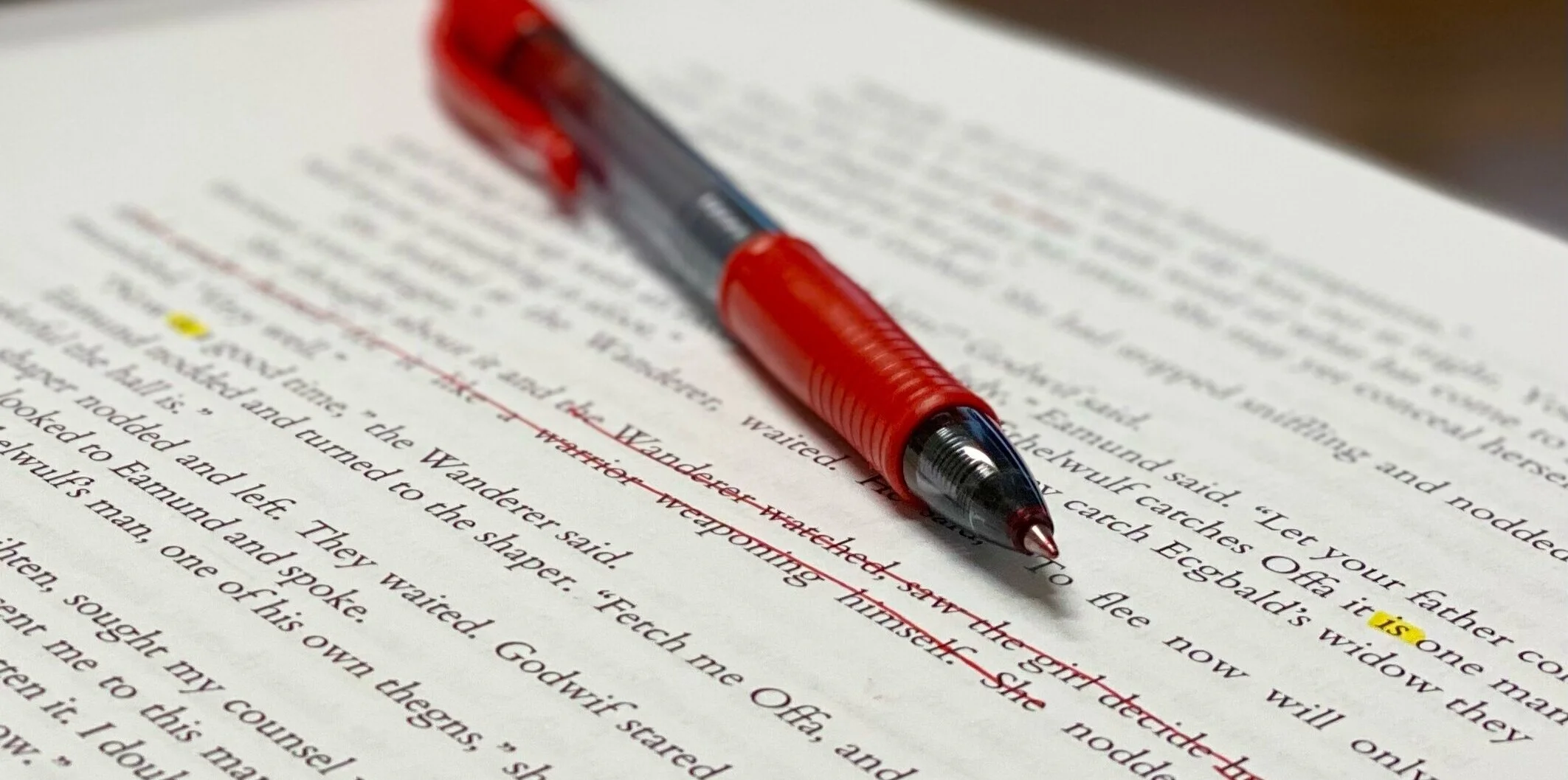

Line-item censorship

/It’s not every day that you see writers at Slate and National Review on the same wavelength. And yet here are Laura Miller at the former and Kyle Smith at the latter reporting on the same story: two novelists who have recently been cowed by internet mobs into deleting not entire passages, characters, or plotlines, but individual lines from already published novels.

The novelists are Elin Hilderbrand and Casey McQuiston, and the novels are, respectively, Golden Girl, a “beach read” about a recently deceased author of beach reads trying to help people from beyond the grave, and Red, White, & Royal Blue, a gay romance in which the President’s son falls in love with one of the princes of the UK’s royal family. A mob of online readers attacked the first for an offhand comment by a teenaged character who compares hiding from her family to Anne Frank hiding from the Nazis in an attic. The second took similar flak for a line in which the President complains about having to make a groveling phone call to the Prime Minister of Israel for political reasons. One was criticized as “anti-Semitic,” the other as “Zionist.” You really can’t win.

And I should quote some of this criticism in more detail. According to one online commenter, the single line about the phone call to Israel in McQuiston’s book “normalizes the genocide & war crimes done by Israel that will always be backed up & unashamedly supported by America.” And, on Goodreads, I find someone who thought the other book’s offhand comparison to Anne Frank was (in bold) “one of the most terrible things I read in a book in my entire life.” (Said reviewer also admits to reading the book only because of the controversy.)

You can read more about both incidents in the Miller and Smith pieces above. Both Hilderbrand and McQuiston apologized and both promised that these lines would be cut from future editions of the book.

Note: these lines would be cut.

Social media is doing some weird things to publishing and storytelling, some of the most high-profile examples being YA books that have been un-published before they were even released based on the perceptions of Twitter mobs. Furthermore, we’ve seen increasing pressure to “cancel,” in the sloppy but commonplace term, books that fall afoul of modern sensibilities, including popular bestsellers like the Harry Potter series and classics as diverse as Gone With the Wind and the Iliad. But here we have precision-bombing attacks on particular lines of text and the authors and publishers caving to the mob’s demands. Here outraged online critics have arrogated to themselves the job of editor.

Perhaps this is an attempt to find a compromise, to save face and avoid total “cancelation” while throwing a bone to small but vocal mobs online. I’m not sure—but the trend worries me, because it has no inherent limiting principle (see the Bradbury piece I link to below) and because the people demanding such changes or cuts are never satisfied. The grave, and the barren womb, the earth that is not filled with water, fire—and Twitter mobs.

The character of the people driving these cuts matters. I wrote “small but vocal” above, and these are small groups. Look up Hilderbrand and McQuiston’s books on Amazon or Goodreads or some other service and, despite the controversy, they still have good ratings. Both currently have 4.6 out of five stars on Amazon, with a whopping 2,600 and 13,000 reviews and ratings, respectively. This suggests that the overwhelming majority of the people who read these books have no problem with them. It’s also telling that, in both cases, the objects of the mob’s ire were throwaway lines of humor or wry, ironic commentary—and obviously so. People who don’t get jokes, who have no sense of humor, or who are too simple or willfully ignorant to understand that a fictional character’s opinions are not the author’s—a point raised by both Miller and Smith—are not worth listening to. More about that below.

But my primary concern with incidents like this is as an author. How can writers protect themselves from the mob and, more importantly, stay true to their craft, not compromising even a line of their work? I have a few ideas:

Get off Twitter. Seriously. All social media are part of the problem (note that some of the criticism mentioned in Miller and Smith’s articles originated on Instagram, in my experience the cheeriest of social media networks), but Twitter is a cesspool, as if all ten bolgia of Dante’s eighth circle were upended into one pit of rage, dishonesty, grandstanding, and bad faith assertion. It’s full of glib, self-assured, vindictive liars who can only think in labels and slogans and who make sure they’re always on the winning side (see below). In a word, it’s full of Fillmors. If you’re on Twitter you’re asking for it sooner or later, and opting out means you don’t have to be present when the mob arrives. And when the mob’s target isn’t present, it loses focus (mobs, like all democratic bodies, being small-minded and fickle) and dissipates faster.

Ignore the mobs. Based on the examples I’ve seen, I’m not sure which is worse—attempting to explain yourself or abjectly apologizing. The former feeds the mob’s outrage; the latter invites the mob to demand more and more specific groveling (about which more below). Woke social media mobs don’t offer good faith criticism or actually want that hoariest of self-serving clichés, “a conversation,” and refusing to participate is the only answer. (Well, perhaps not the only answer: mockery would be best, the devil being unable to tolerate scorn, but I can’t fathom the bravery that would take. I don’t think I have it.)

Don’t make decisions based on idiots. Lie down with dogs, wrestle with pigs, etc. This should be common sense. Overlaps generously with the first two points above.

Don’t play games you can’t win. As children, we all knew someone who tried to manipulate our playground games so that they could come out on top every time, and that’s precisely what’s going on with all of these controversies. The only differences are the artificially heightened stakes and po-faced moralism—and the attending fear of wrongdoing—that come along with it. This is still a game, and it’s childish. Witness Tom Hanks, who seems to me a genuinely intelligent, decent, and well-intentioned man, and who recently jumped on the Tulsa Riots bandwagon to reflect on the “whiteness” of the history he learned growing up. Not good enough, his critics were quick to aver, because it’s never good enough. See also Lin-Manuel Miranda. And American Dirt. And, graphically, this. There’s always something more and more granular to acknowledge, “educate yourself” on, or “do better” about, and attempting to explain yourself or admitting guilt means you lose. Automatically. Those kids who did this on the playground eventually learned to play by coherent, ironclad, finite rules comprehensible and applicable to everyone—or they played by themselves. Again: refuse to participate.

On a final, more positive note—Be yourself. This is a truism from those painful years of learning to date, but nothing is more attractive than a person doing what they like to do because they like to do it. Write the stories you want to write the best way you see fit, and don’t adapt or apologize to appease some offended party, real or imagined. This is an honest way to work, based on love, and it builds genuine community with people who love the same things you do. And, as a bonus, you’ll produce art you can be proud of.

Even with those observations and admonitions out of my system (and I’m preaching to myself as much as anyone there), I look at these two incidents and am still left with questions. There are questions with obvious answers, questions about why the authors or publishers would so cravenly knuckle under to such baseless criticism, but the one I keep asking and have been asking a long time has to do with the members of the mob:

Why do these people bother reading novels?

Why even pick up the book in the first place? What’s the point? Why live this way? Why not write your own stories if those crafted by others are so problematic? Why not just give up fiction altogether and stand in front of the mirror, cooing over your own enlightenment?

I’m not sure I have any insight into this beyond the obvious—the sense of superiority offered by woke ideology, the addictive high of bringing writers and publishers to their knees and making them do things. And control, making others do things, is what this is ultimately all about.

At any rate, this kind of thought policing, to use Smith’s term, is illiterate, incurious, and fatal to the imagination. It sees representation where we should see characters, messaging where we should see themes, and the pieces of a vast game of power and politics where we should see stories. Rather than going out of oneself into strange, wonderful, and terrible new worlds, it demands conformity to the reader’s standards. It is anti-art. Even the much-vaunted empathy that reading fiction is supposed to build finds no purchase in the barren, pride-withered souls of these readers.

But we shouldn’t expect this kind of behavior to correct itself soon. As John Gardner noted in On Becoming a Novelist: “Character defects fed by self-congratulation are the hardest to shed.” In the meantime, authors should stay true to their calling—carry the fire, in an evocative phrase from one of my favorite books—and refuse to compromise even a line.

More if you’re interested

For a striking presentiment of the damage readers with ideological axes to grind can do, read Ray Bradbury’s 1979 coda to Fahrenheit 451, available here. I’ve gotten irritated about the ideological demands made on good storytellers before, which you can read more about here.