The Bomber Mafia

/The Sandman, a B-24 Liberator, flying through the smoke above the Ploiesti oil refineries in Romania, August 1, 1943

War is hard on idealists. It proves especially cruel to those modern idealists who have turned so often to technology, inventing new weapons or instruments of war, in hopes of saving lives. One thinks of Richard Gatling, inventor of the first practical machine gun, who developed his weapon after seeing thousands of men on both sides of the Civil War wasted with wounds, disease, and in the stand-up slaughter of battle itself. The firepower his Gatling gun offered, he believed, would “supersede the necessity of large armies.” He could not have foreseen how wrong that hope would be.

Gatling died the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and just over a decade later both tools—the machine gun and the airplane—would raise the scale of slaughter in modern warfare to unimaginable heights. The devastation of the First World War, with twenty million dead to little perceivable gain, shocked the sensibilities of a world confident in its so far uncontested forward progress.

Idealists and theorists

The Bomber Mafia, half of the subject of Malcolm Gladwell’s newest book, came along in the aftermath of that war. Surveying the destruction of the war and cognizant of the possibilities of more war in the future, a band of renegade pilots at the out-of-the-way Maxwell Field (now Maxwell-Gunter AFB) in Alabama gradually built a new doctrine of air power. These pilots noted the knock-on effects on the American aviation industry after the destruction of a ball-bearing factory in Pittsburgh and theorized that, by precisely targeting industries critical to an enemy’s military production, fleets of heavy bombers could cripple the enemy and end the war quickly and with little—or at least less—battlefield bloodshed.

Their fervency—Gladwell refers to members of this inner circle as the “true believers”—and their insistence on their as yet untested theories earned them their nickname, which was not meant to be flattering. But the Mafia stuck with it, and the key to their strategy was a piece of technology, a top secret precision instrument called the Norden bombsight. The bombers of the First World War dropped bombs pretty much indiscriminately, and sometimes even by hand. For the Mafia’s idea to work, they would need to be able to drop bombs accurately onto specifically selected targets; the Norden bombsight promised to deliver that.

The bombsight was the invention of Carl Norden, a Dutch engineer who fervently believed in the possibilities opened up by his work. The bombsight was an extremely complex analog computer that factored in speed, altitude, windspeed, and even the rotation of the earth on its axis to enable a trained bombardier at high altitude to site, aim at, and hit targets on the ground—an unimaginable feat during the First World War. The Norden required only clear skies and daylight.

Norden is another of the idealists in Gladwell’s book, and offers a striking contrast to the hotshot pilots of Maxwell Field. Where one of Gladwell’s other focal points, Haywood Hansell Jr, was a chivalrous Southerner, a career Army officer, and scion of six generations of leaders in both the US and Confederate armies, Norden was a private, hard-driven, exacting technician, and a deeply religious man. What the two had in common—through Hansell’s chivalry and Norden’s Christianity—was a moral concern to make warfare as quick, humane, and bloodless as possible. Precision daylight bombing could take the ever-expanding scope of modern warfare and reduce it, shrinking it back toward the old ideal of warriors fighting only other warriors, a throwback to the centuries before Sherman or Napoleon.

Tellingly, Gladwell notes, Hansell’s favorite book was Don Quixote.

Reality ensues

The Bomber Mafia’s doctrine was the result of this confluence of theory and technology, and they finally got their chance to test their ideas with American entry into the Second World War. Members of the Bomber Mafia held key strategic positions in the Eighth Air Force in Europe. These men resisted pressure from the British to join the RAF in “de-housing” or “area bombing”—euphemisms for indiscriminate nighttime bombing of heavily populated urban areas—in favor of carefully planned large-scale daylight raids on key factories, exact implementation of the Bomber Mafia’s dearly held doctrine.

But reality intervened. The fleets of bombers required for these raids had difficulty coordinating their attacks and were vulnerable to flak and German fighters, and weather proved a persistent problem, either fog delaying the start of bombing missions in England or clouds obscuring the targets over Europe. Worse, and more fatally for the Mafia’s doctrine, high altitude flight plunged the crews and equipment of American bombers into temperatures as low as -60° F, causing the oil in Norden’s precision instruments to congeal ever so slightly, introducing just enough friction and throwing off their tolerances just enough to rob the bombers of their vaunted accuracy.

The peak of the Bomber Mafia’s career came with two raids on Germany on August 17, 1943. The first raid targeted the Messerschmitt aircraft factory at Regensburg and was a diversion meant to draw off the fighters that would inevitably attack any large formation of Allied bombers. If the Messerschmitt plant could also be destroyed, so much the better. But the second raid, timed for slightly later in the day, was the main effort and aimed at a ball bearing factory in Schweinfurt—precisely the kind of industry-crippling target the Mafia had developed their ideas around. After weather delays, the two missions launched, now several hours apart, leaving plenty of time for the Germans to regroup and attack again.

Both raids were savaged. Here’s Gladwell’s description of just one B-17 on the mission to Regensburg; the bomber was

hit six times. One twenty-millimeter cannon shell penetrated the right side of the airplane and exploded beneath the pilot, cutting one of the gunners in the leg. A second shell hit the radio compartment, cutting the legs of the radio operator off at the knees. He bled to death. A third hit the bombardier in the head and shoulder. A fourth shell hit the cockpit, taking out the plane’s hydraulic system. A fifth severed the rudder cables. A sixth hit the number 3 engine, setting it on fire. This was all in one plane. The pilot kept flying.

Between them, the two raiding forces lost sixty bombers—meaning over 550 airmen—with many more heavily damaged. The Schweinfurt ball bearing factory was damaged but quickly repaired. Civilians were killed anyway. A second raid two months later met with similar results and took similar losses.

Tinkerers and pragmatists

The failure of precision bombing brought other characters with opposite qualities to the fore.

Carl Norden and his meticulously crafted bombsight gave way to a team of chemists working for the NDRC, the National Defense Research Committee, the same government agency that would produce the atomic bomb. Rather than the high-minded principles and moral qualms of Norden, these chemists were simply curious. They heard about an odd chemical reaction at a paint factory that produced intense fires and started poking into it, looking for ways to amplify the effects of the reaction—hotter, more intense, longer burning fires. They brought in architects to mock up German and Japanese towns and repeatedly bombed them, carefully assessing the relative effectiveness of different flammable compounds. They tinkered with and tested these new incendiaries and eventually produced a weapon far more destructive than the fire-starting bombs dropped on German cities by the British—napalm.

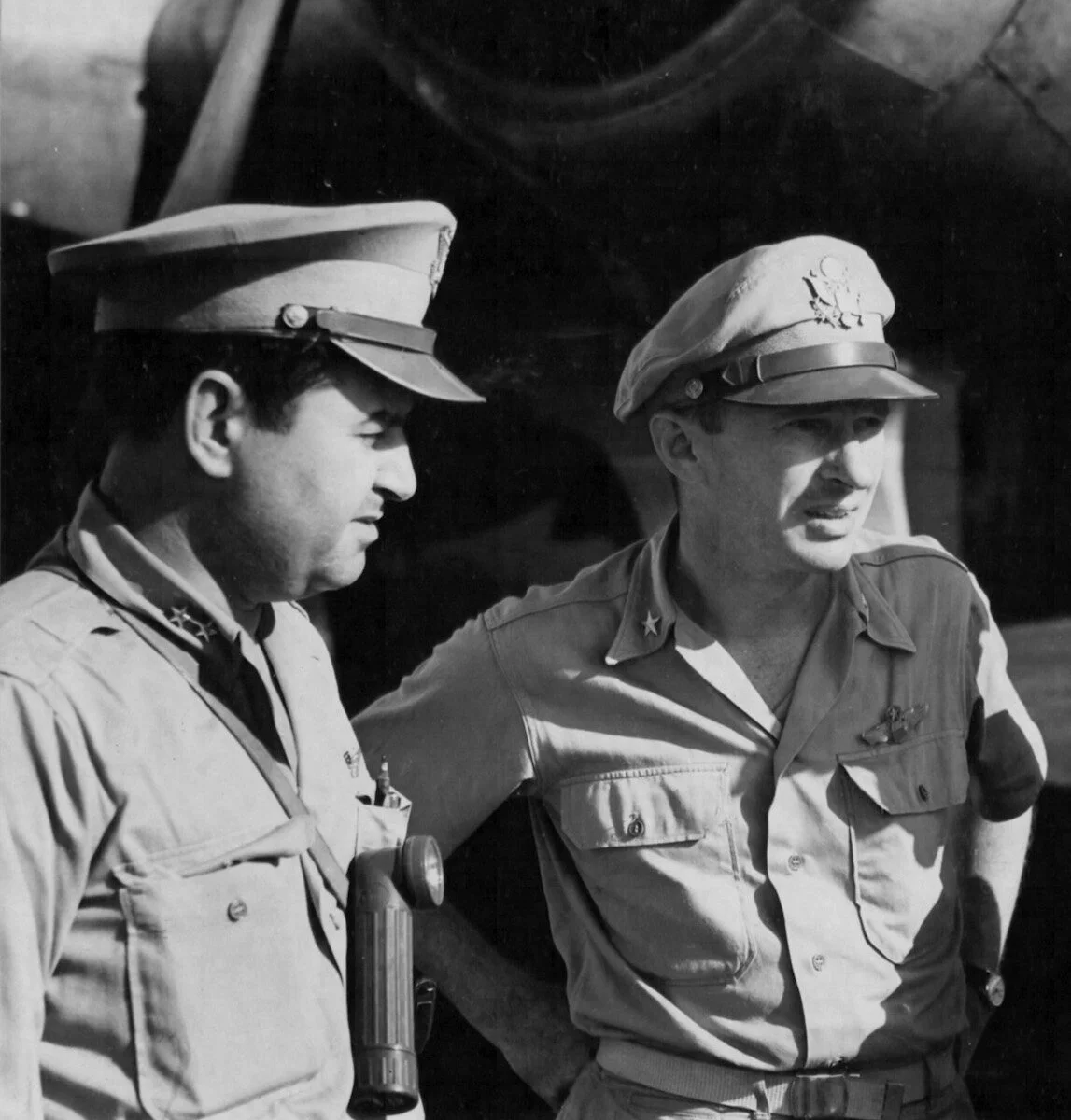

Pragmatist Curtis LeMay (left) arrives in the Marianas to replace idealist Haywood Hansell (right) in early 1945

In the air, the Bomber Mafia came to the end of its run. Hansell had transferred to the Pacific to lead precision bombing of Japan from the Marianas, and tried carefully to target Japanese industry the same way and for the same reasons he had in Germany, and with the same limited results. In the incident with which Gladwell opens his book, after several months of this Hansell was brusquely notified of his replacement by a former subordinate and philosophical opposite, the commander of the Regensburg raid—Curtis LeMay.

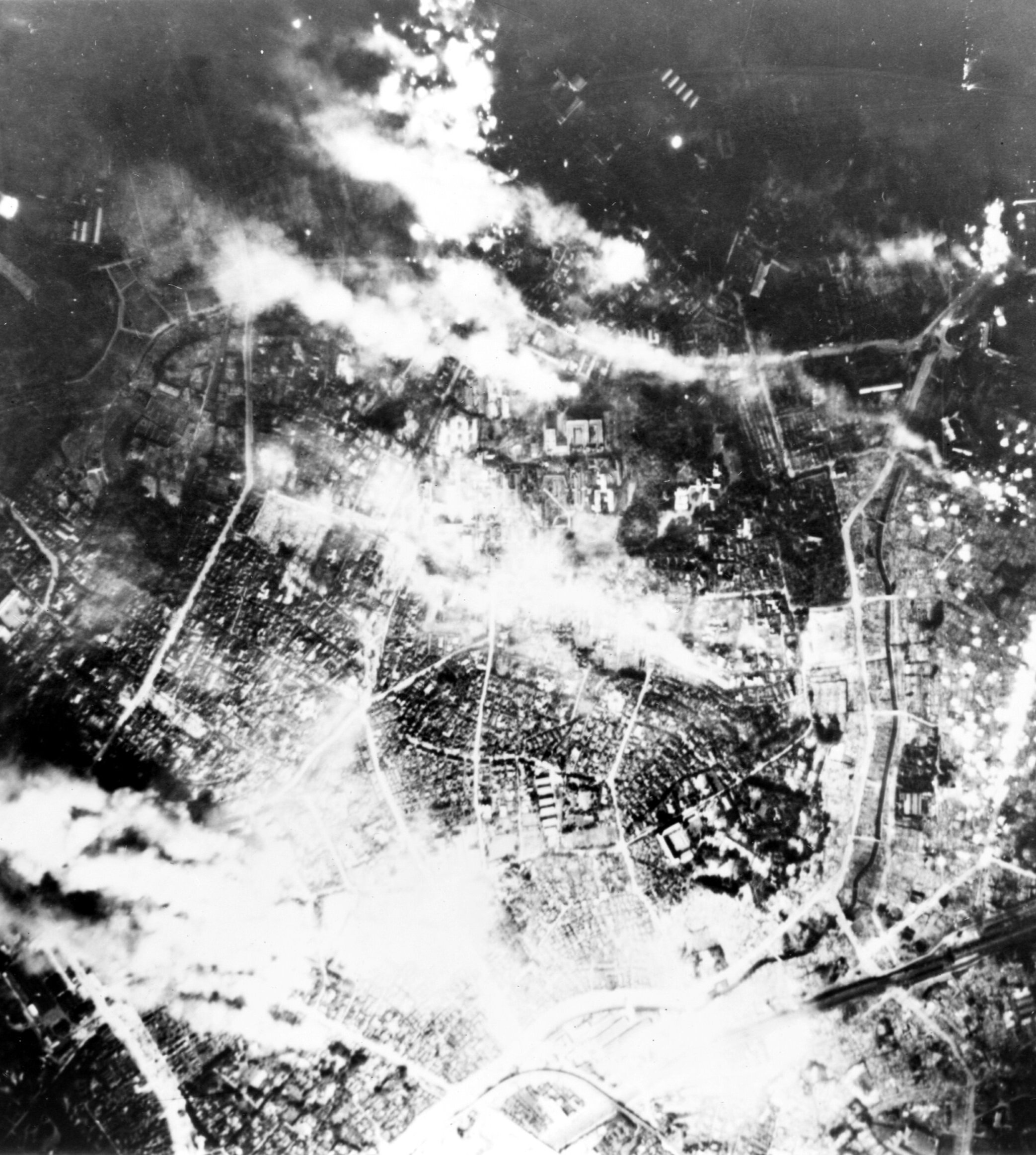

LeMay, a hardbitten and taciturn Ohioan (the murderous Midwesterner is something of an American military tradition, it seems), had embraced area bombing in Europe and, with the new technology of napalm at his disposal and knowledge of the highly combustible materials used in traditional Japanese architecture, immediately launched a campaign of firebombing in Japan. The “longest night of the Second World War” alluded to in the subtitle of the book is the night of March 9-10, 1945, in which LeMay’s long-range B-29 Superfortress bombers targeted Tokyo—not an industry or war-critical facility or defensive installation, the city of Tokyo itself. More than 300 bombers hit the city over the course of

almost three hours; 1,665 tons of napalm were dropped. LeMay’s planners had worked out in advance that this many firebombs, dropped in such tight proximity, would create a firestorm—a conflagration of such intensity that it would create and sustain its own wind system. They were correct. Everything burned for sixteen square miles.

As many as 100,000 people were killed—burned alive. And LeMay would go on to bomb a total of sixty-seven Japanese cities with similar effects, all months before the atomic bombs that ended the war were even ready.

Why? Because it worked. LeMay believed so, and Gladwell even quotes Japanese historians who express a grim gratitude for the bombing in the belief that it shortened the war and prevented either Japan’s annihilation or its partition by the Soviets. The failure of the Bomber Mafia to circumscribe the destruction and provide a surgically precise ending to the war by destroying enemy logistics opened the door to the cold-blooded and amoral pragmatists, the people who care only about what works—a lesson in the amorality of technology.

But at what cost? This is a profound question that Gladwell raises but to which he refuses to provide easy answers, because there are none. The terms of the question itself, and the real-life consequences to which it alludes, should bother us.

Praise and criticism

For such a slender book there’s still a lot I’m leaving out in my description of The Bomber Mafia. Gladwell’s account of American pilots flying “over the hump” from India to China on their way to Japan is harrowing, and points to his strengths as a writer and storyteller—the hook, the unusual angle, the seemingly out-of-place but illuminating side topic, and above all the telling detail. His writing is also exceptionally brisk and vivid. See the block quotes above for a couple examples.

I appreciated that Gladwell did not succumb to the easy accusation of racism in the bombing of Japan that is prevalent in a lot of discussions of the war today. I also liked the sense of moral, philosophical, and even theological seriousness Gladwell brought to the topic. He even frames “the temptation” of the subtitle—the question of whether to use indiscriminate area bombing just to get results—as equivalent to the deals for power that Satan offered to Jesus in the wilderness. Jesus, famously, said no. The Allies and the US military, on the other hand…

Tokyo burns again, May 26, 1945

Furthermore, Gladwell brings human character and personality to the fore in this book in a refreshing way. I’ve seen a few reviewers fault Gladwell for supposedly reducing the tensions within the US military over targeting civilians to a personality clash. That’s not really what’s going on; Gladwell uses Hansell and LeMay and others as avatars of the deeprooted philosophical differences, of two different approaches to the use and morality of technology in warfare, and what’s refreshing about it is his recognition that, on top of all this, personality still matters. Character may not be destiny, but it is nonetheless a large part of it.

But The Bomber Mafia is not a perfect book, of course. While imminently readable, it sometimes reads like the transcript of a podcast—which, in a way, it is, as Gladwell first developed this story as an audiobook. That genesis shows most clearly in how Gladwell uses sources: rather than quoting or citing books, he always introduces outside information by way of interviews (e.g. “I talked to so-and-so about such-and-such, and he said…”). Gladwell has clearly done a lot of research into this topic and found a striking way to present it, but the approach of the writing is sometimes a little too informal. But that’s a relatively minor nitpick.

Some reviewers have faulted Gladwell for insufficient coverage of the issues involved in strategic bombing. Certainly The Bomber Mafia is in many ways a cursory look at the subject, but Gladwell in no way means this story to be exhaustive. He has done what he’s good at—found enough loose threads and unusual approaches to bring fresh insight and raise good questions. More seriously, I’ve seen at least one review accusing Gladwell of glorifying and promoting more recent American bombing. Such a reviewer can’t have been paying much attention; Gladwell clearly presents the horror and death resulting from area and firebombing, and goes out of his way to note the hesitations and sometimes outright refusals of American pilots to participate, incidents he presents as indicative of a troubling change in American air strategy.

These are issues worth considering, but The Bomber Mafia is mostly excellent—a great surprise in my reading. Most surprising to me was the sympathy Gladwell evoked in me for Curtis LeMay (I am ever more the old-fashioned anti-pragmatist as I get older and as I study more and more what warfare since the collapse of chivalry has meant for the innocent). And there is again the set of questions Gladwell advances, both explicitly and implicitly, about morality, technology, warfare, and what it takes to win.

Conclusion

Thanks to its readability, its vivid attention to personality and what it was like for those who lived through these events, its exceptionally lucid explanation of complicated ideas and technologies, and its clear-eyed awareness of the consequences of the technologies it describes, The Bomber Mafia is an outstanding introduction to an important historical topic that still raises hard questions about morality and technology, about ends and means. I look forward to recommending this to students not only in my US and Western History classes, but in a course like Technology & Culture as well. This is worth checking out, and the Memorial Day weekend might just be the best time to do so.