Which is it?

/One of the peculiar annoyances of medieval history is the license even good historians seem to give themselves to make sweeping generalizations, only to qualify them to the point of contradiction later.

Here’s Tore Skeie in his otherwise excellent book The Wolf Age: The Vikings, the Anglo-Saxons, and the Battle for the North Sea Empire, in the middle of a discussion of the remarriage of Æthelred Unræd’s widow Emma of Normandy to his conqueror, Cnut the Great:

But despite her status and central position in this drama, it is more difficult to obtain a clear picture of Emma than of the men around her, for the simple reason that she was a woman. The men who recorded the course of history—mostly monks—almost never mentioned women other than when they were married off or acted on behalf of their husbands or sons. The kings’ wives, sisters, mothers and daughters—all of them remain almost invisible to us, even though they were often deeply involved in everything that went on and could be accomplished and independent political players in their own right.

And in the next paragraph we read:

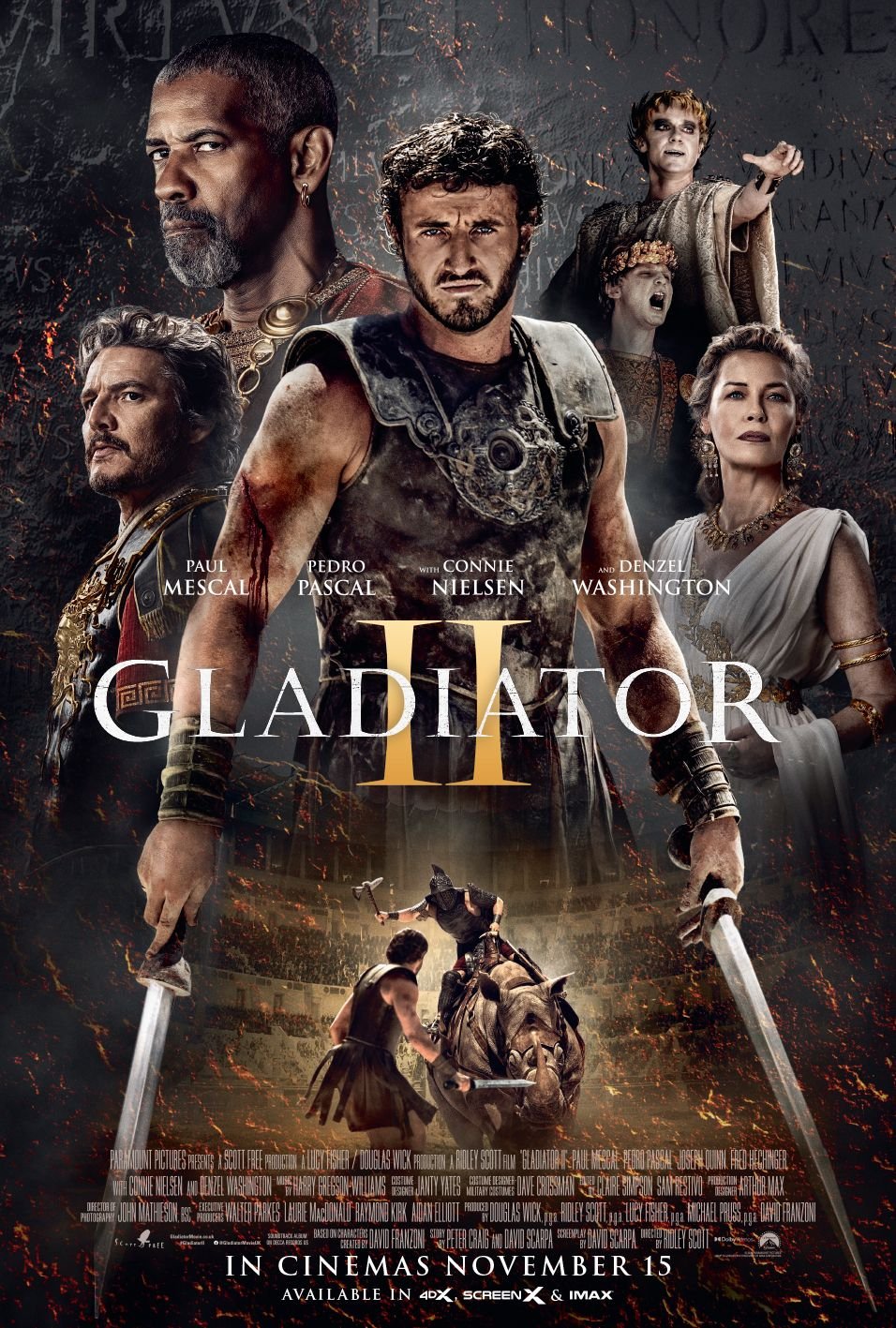

Emma of Normandy (c. 1984-1052) in her Encomium receiving the manuscript from its authors

One of the most important sources from this period is the Encomium Emmae Reginae, a tribute to Emma and the people around her written at her request later in life, probably by a Flemish monk.

Typical! Nasty old patriarchy-loving sexist monks ignoring a powerful woman, erasing her from history... Right up until they write a dedicated biography of her at her command.

The truth is that it is “difficult to obtain a clear picture” of anyone for most of history, men and women, high and low. Even the more heavily documented men in this story seldom reveal much of a personality or motives behind what they do or the particular courses they take, and even the most important of them simply disappear from the record for years at a time. In his short biography of Cnut for the Penguin Monarchs series, Ryan Lavelle records the king’s death thus:

Cnut died in Shaftesbury in November 1035 at about forty years of age. We don’t know why he died there or what he was doing at the time.

That’s two short sentences, but go back over them and really consider just how much they indicate we cannot know about the most powerful man in northern Europe at the time of his death. Even his age is approximate. The rest of the book is full of such passages beginning with “maybe,” “probably,” “possibly,” and “we don’t know.” The “invisibility” of people in historical sources, especially the Early Middle Ages, has more to do with the purpose and built-in limitations of the sources than sexism.

The generalization in that first paragraph from The Wolf Age does not so much inform the reader about medieval culture and historiography than affirm a dearly held modern prejudice. And this prejudice, much like that passage’s imaginary chauvinist monks, renders the close-following contradiction invisible to the right-thinking modern person.

For two other examples of modern preconceptions blinding the historian and the reader to medieval minds, see here—an example coincidentally also involving Cnut—and here. Like the imputations of sexism in the example above, these faults—cynicism and a reductive “seeing through”—warp our perception of the past. For a better approach, Tolkien is always a good place to start, as here.