On History in Fiction (and Vice Versa)

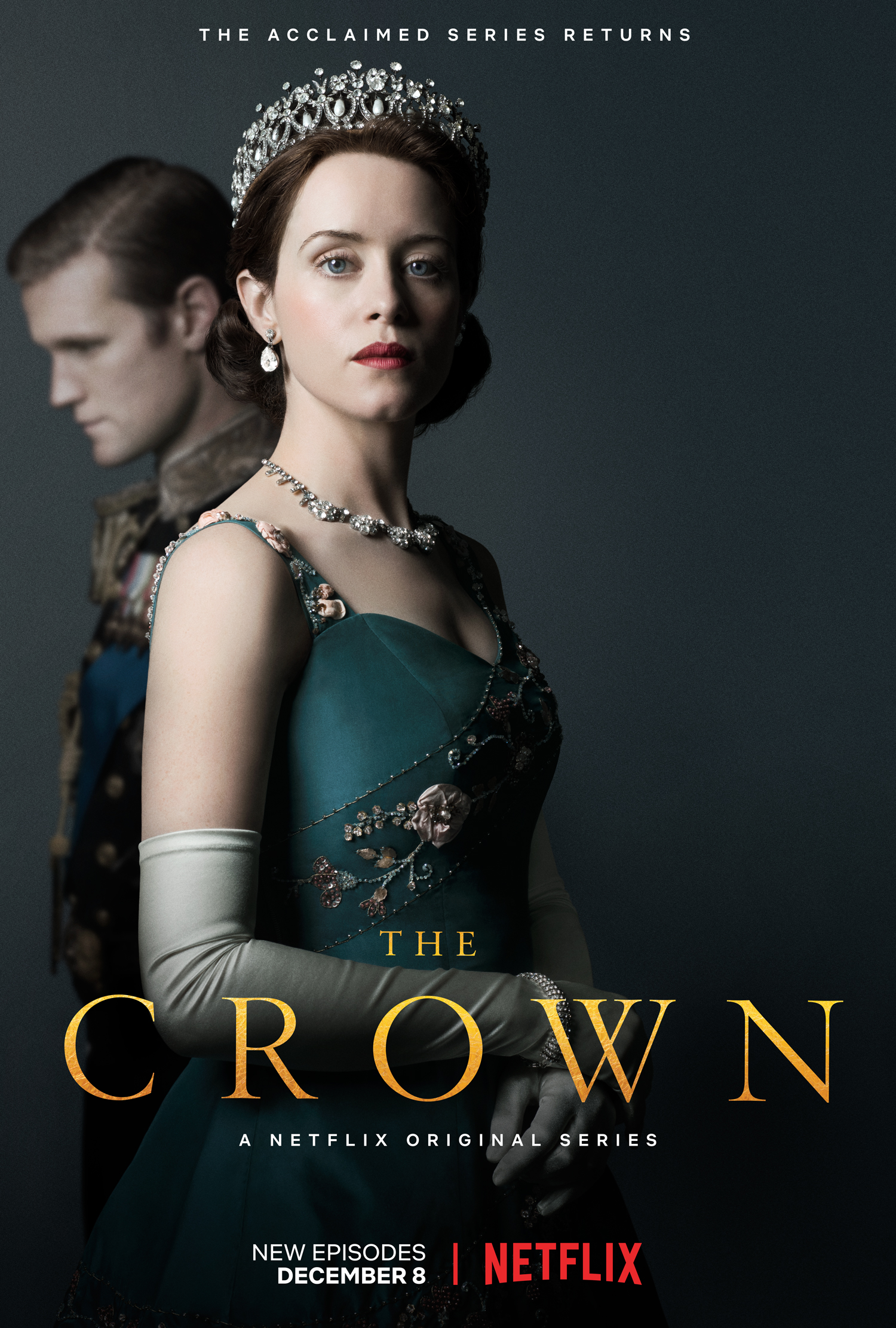

/Last month, Peggy Noonan had a column in the Wall Street Journal about what is at stake in inaccuracy—or, perhaps, misrepresentation—in historical films. Noonan wrote in response to season two of The Crown and Steven Spielberg's latest film The Post. If her summaries are accurate she raises some legitimate but relatively minor concerns, but she rather hyperbolically calls these inaccuracies "lies" and writes that, through depicting JFK as a smoker and Nixon as a malevolent criminal power withholding the Pentagon Papers to protect himself, "we are losing history."

Today, Christopher J. Scalia, son of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, responded with a column on the virtues of even inaccurate historical films.

I both teach history and write historical fiction, so I care deeply about the uneasy marriage of history and fiction in that genre label. I also think Scalia has the better argument.

Scalia draws from Sir Walter Scott, author of immensely popular 19th-century romances—what we would today call "historical novels"—to make his point. Briefly, Scott responded to accusations that he had, in novels like Ivanhoe, "adulterat[ed] the pure sources of historical knowledge" or, in Noonan's terms, lied about the past. The danger represented by his inaccuracies or adulterations is described in terms strikingly similar Noonan's: Scott was "causing history to be neglected—readers being contented with such frothy and superficial knowledge, as they acquire from your works, to the effect of inducing them to neglect the severer and more accurate sources of information."

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832)

Scott's critics had a point—if they were looking for pure accuracy in his novels. Ivanhoe is replete with medieval stereotypes and anachronistic howlers. But pure accuracy was not his concern; telling a good story was.

Here, Scott's defense gets interesting, and he makes a point I have felt intuitively but never seen put into words before. The benefit of even a book like Ivanhoe is that, if the story excites and entertains—delights, in one half of Horace's formulation—and does these things well enough, the reader who has been touched by the story will seek out the truth behind it:

I have turned the attention of the public on various points, which have received elucidation from writers of more learning and research, in consequence of my novels having attached some interest to them.

Or, in Scalia's words: "Historical fiction actually promotes interest in purer history."

I might amend this to "good historical fiction," since there must be excellence in execution for any art to be effective, but Scalia's summary is, in my experience and observation through hundreds of novels and films, exactly right. Accurate, if you will.

How many readers have—on their own—dug deeper into Anglo-Saxon England or the Napoleonic Wars because of Bernard Cornwell? Or ancient Rome because of Colleen McCullough? Or Greece because of Stephen Pressfield, High Medieval Europe because of Umberto Eco, the Tudors because of Hilary Mantel, or Texas, Hawaii, Poland, and large tracts of the rest of the world because of James Michener?

All of these writers' books have problems—some of them serious, and worth serious consideration—but they have all successfully interested the public in the past, and that's something. Fiction may be the first history that many untrained readers come to, but it is often not the last.

Read both Noonan's and Scalia's pieces; they're both worth your while. I have much more I could write, especially on the reaction of some historians to a fine film like Dunkirk, but those thoughts can wait for another day.

A final thought on the value of fiction from G.K. Chesterton, a passage I return to again and again, which I'll close with sans commentary:

No wise man will wish to bring more long words into the world. But it may be allowable to say that we need a new thing; which may be called psychological history. I mean the consideration of what things meant in the mind of a man, especially an ordinary man; as distinct from what is defined or deduced merely from official forms or political pronouncements. . . . It is not enough to be told that a tom-cat was called a totem; especially when it was not called a totem. We want to know what it felt like. Was it like Whittington's cat or like a witch's cat? Was its real name Pashtl or Puss-in-Boots? That is the sort of thing we need touching the nature of political and social relations. We want to know the real sentiment that was the social bond of many common men, as sane and as selfish as we are. What did soldiers feel when they saw splendid in the sky that strange totem that we call the Golden Eagle of the Legions? What did vassals feel about those other totems the lions or the leopards upon the shield of their lord? So long as we neglect this subjective side of history, which may more simply be called the inside of history, there will always be a certain limitation on that science which can be better transcended by art. So long as the historian cannot do that, fiction will be truer than fact. There will be more reality in a novel; yes, even in a historical novel.

—from The Everlasting Man