A sick man's appetite

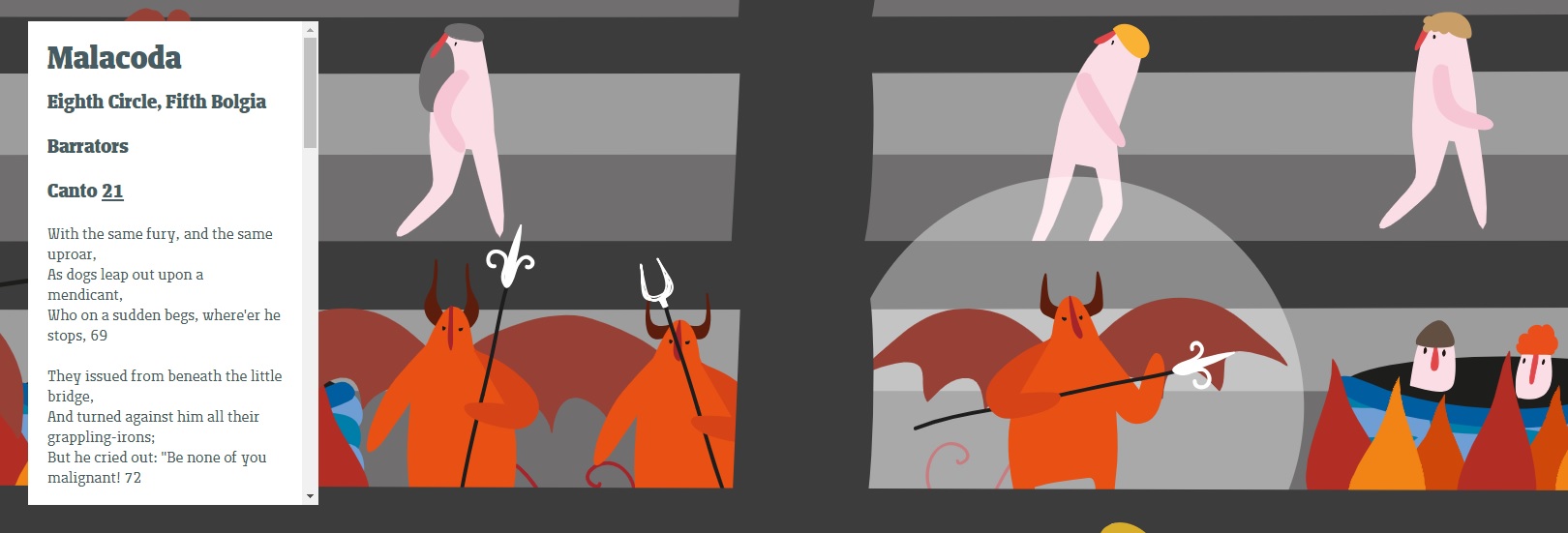

/Epic entrance: Ralph Fiennes as Gaius Marcius confronts the plebs in Fiennes’s film adaptation of Coriolanus

Kevin Williamson wrote an interesting piece recently on the acquiescence of major news organizations to the realities of Twitter mobs. He begins with a meditation on one of Shakespeare’s less well known plays, Coriolanus, and the amazing entrance of its title character, the Roman general Gaius Marcius Coriolanus.

In Scene I, Act I, Coriolanus confronts an angry mob of plebeians— “mutinous Citizens” armed “with staves, clubs, and other weapons,” according to Shakespeare’s stage directions—who threaten to riot over the price of bread. Though hostile to Coriolanus—no more than five lines into the play they call him the “chief enemy to the people”—upon his appearance they hail him as “noble Marcius.” Already having the measure of the mob, he responds with a putdown, and when their leaders say “We have ever your good word,” trying to initiate an exchange of flattery, Coriolanus launches into the first of his several short but savage speeches:

He that will give good words to thee will flatter

Beneath abhorring. What would you have, you curs,

That like nor peace nor war? The one affrights you,

The other makes you proud. He that trusts to you,

Where he should find you lions, finds you hares;

Where foxes, geese: You are no surer, no,

Than is the coal of fire upon the ice,

Or hailstone in the sun. Your virtue is

To make him worthy whose offence subdues him

And curse that justice did it. Who deserves greatness

Deserves your hate; and your affections are

A sick man’s appetite, who desires most that

Which would increase his evil. He that depends

Upon your favors swims with fins of lead

And hews down oaks with rushes. Hang ye! Trust Ye?

With every minute you do change a mind,

And call him noble that was now your hate,

Him vile that was your garland. What's the matter,

That in these several places of the city

You cry against the noble senate, who,

Under the gods, keep you in awe, which else

Would feed on one another? What's their seeking?

Williamson’s interest in his piece, prompted by this New York Times article and especially journalist Masha Gessen’s comments in it, is the capitulation of news organizations to social media mobs. The “morality clauses” discussed there seem to be—by the most charitable interpretation I’m capable of—legal mechanisms for covering a news organization’s butt, at the expense of its writers, in the event of a Twitter outrage mob. While I agree this is a risible, even craven trend which will only encourage online rabblerousers and Williamson argues his point eloquently, something else in Coriolanus’s introductory speech, something related but tangential to Williamson’s angle, stuck with me.

Near the middle of his harangue, Coriolanus tells the mob of angry citizens that “your affections are / A sick man’s appetite, who desires most that / Which would increase his evil.”

Can there be any better metaphor for our social media addiction?

Barring the word addiction itself—which is more literal than metaphorical now anyway—I don’t think so. We have a lot of electronic opiates available to us—games, memes, videos, gossip, pornography, and more, all of it soaked in one form of satisfied self-affirmation or another and a retreat from the world. But the most dangerous electronic drug has to be outrage, because unlike any of those others it imparts to the addict a sense of purpose and moral uprightness and, worst, an illusion of caring about the real world. And the more we indulge, the worse it gets.

I’ve been mulling over two examples for some time: one recent, one ancient history (by internet standards).

The first is last weekend’s Covington Catholic incident at the March for Life in Washington, DC, a story everyone, whether they like it or not, should be familiar with. I can’t add much to the discussion there—the misinformation, the superheated Twitter mob, the public pillorying, the death threats were all despicable, the more so for being a kneejerk reaction—but keep this example in mind.

The second example I observed by accident on Facebook a few months ago. A post from a Florida sheriff’s department popped up in my newsfeed because a friend from college—a Florida native serving in the Marines—commented on it. The headline was certainly attention grabbing: a Florida man (“Har har,” says the entire Internet instantaneously) had been reported to and arrested by this heroic sheriff’s department after he was observed having sex with a miniature horse. He immediately confessed. The post included details, a mugshot of the offender (a pretty ordinary looking 21-year old man), and—of course—a picture of the horse.

Fortunately, before simply clicking away in disgust, I decided to see what my friend had written in the comments. There were hundreds, and the story had been shared and “liked” nearly a thousand times. He asked, pretty simply, why the sheriff’s department was bothering to publicize this story. As replies stacked up under his comment, I realized there was more to the story than the sensationalism provided by the sheriff’s department: the suspect had severe mental handicaps requiring medication and had lived alone since his mother’s suicide.

In response to my friend’s honest and justifiably pointed “Why?” one commenter wrote: “To let us know what is going on I’d assume.” His reply: “What does this news do for you?”

What I realized in observing this exchange was that a sick man, having already lived through 21 years of difficulty and pain, was being paraded to the public by the authorities for clicks. What’s worse, as the responses to my friend made clear, the prurient Facebookers could justify their leering and hooting by invoking a vague “right to know.” The Victorians had their freak shows, something that should turn the stomachs of all of us; but we have Facebook, and we’re ready with the “likes.” Our response to a real life tragedy converted to electronic stimulus is mere consumption. The tiny number of commenters who were actually familiar with the situation expressed only sympathy, not outrage, disgust, or Bojack Horseman memes.

To return to Covington Catholic and the incident at the Lincoln Memorial, the best piece I’ve read so far on that debacle is this short essay by Julie Irwin Zimmerman at The Atlantic. Zimmerman was among the outraged as the story developed last weekend. She even began castigating her own kids—tellingly, via text message—about the story as it developed. Within two days, as a fuller picture emerged, her view changed and to her credit she repented. She writes:

Take away the video and tell me why millions of people care so much about an obnoxious group of high-school students protesting legalized abortion and a small circle of American Indians protesting centuries of mistreatment who were briefly locked in a tense standoff. Take away Twitter and Facebook and explain why total strangers care so much about people they don’t know in a confrontation they didn’t witness. Why are we all so primed for outrage, and what if the thousands of words and countless hours spent on this had been directed toward something consequential?

The same sentiment my friend had expressed, two months later and in entirely different circumstances. If there’s an upside to this shameful display, it’s that it's very publicity could make it a widely understood example, something we can learn from. But I doubt it.

Williamson, for his part, published a complementary piece this week that unpacks a little bit of what keeps the outrage snowball rolling: self-radicalization, self-selection (creating bubbles or echo chambers), extremism, and, perhaps most crucially, the absence of a hierarchy of credibility. “[T]he only hierarchy that remains,” he writes, “is the crude hierarchy of popularity.” Think of the likes, shares, and jocular comments on that pitiful personal tragedy in Florida trumpeted to the masses on a sheriff’s Facebook page. “Rage and extremism build audiences, especially on social media.” Think of Covington Catholic—or any one of hundreds of similar examples in the last few years. Anyone remember Justine Sacco?

And while it would be tempting, especially for those of us inclined to Luddism, to blame Twitter or smartphones, the truth is that we can’t just blame our technology “The news is there for people who want it,” Williamson writes. “The problem is: Most don’t.” We have to want the right things, and we don’t.

We are, as we try very hard to forget, the real problem. Shakespeare, through Coriolanus, anticipated this. “What’s the matter,” he asks in that first speech,

That in these several places of the city

You cry against the noble senate, who,

Under the gods, keep you in awe, which else

Would feed on one another?

The urge to outrage and mob violence and scapegoating is always there, but the beliefs, institutions, and practices that keep those urges at bay—religion, family, honor, government, law enforcement, established and credible news sources, personal virtue—are not, as we’ve learned. We are no longer awed by anything. How could we be? We have spent decades tearing them down and enjoying it. Now we live for our fix, to give in to our appetites. We’re sick. And absent a recovery of the qualities that keep our will to gawk, to leer, and to participate in others’ public calamities, we will only increase our evil.

As more and more examples make clear, the mutinous citizens, armed with their phones and Twitter and Facebook accounts, are more than willing to feed on one another.