The podcast Stasi

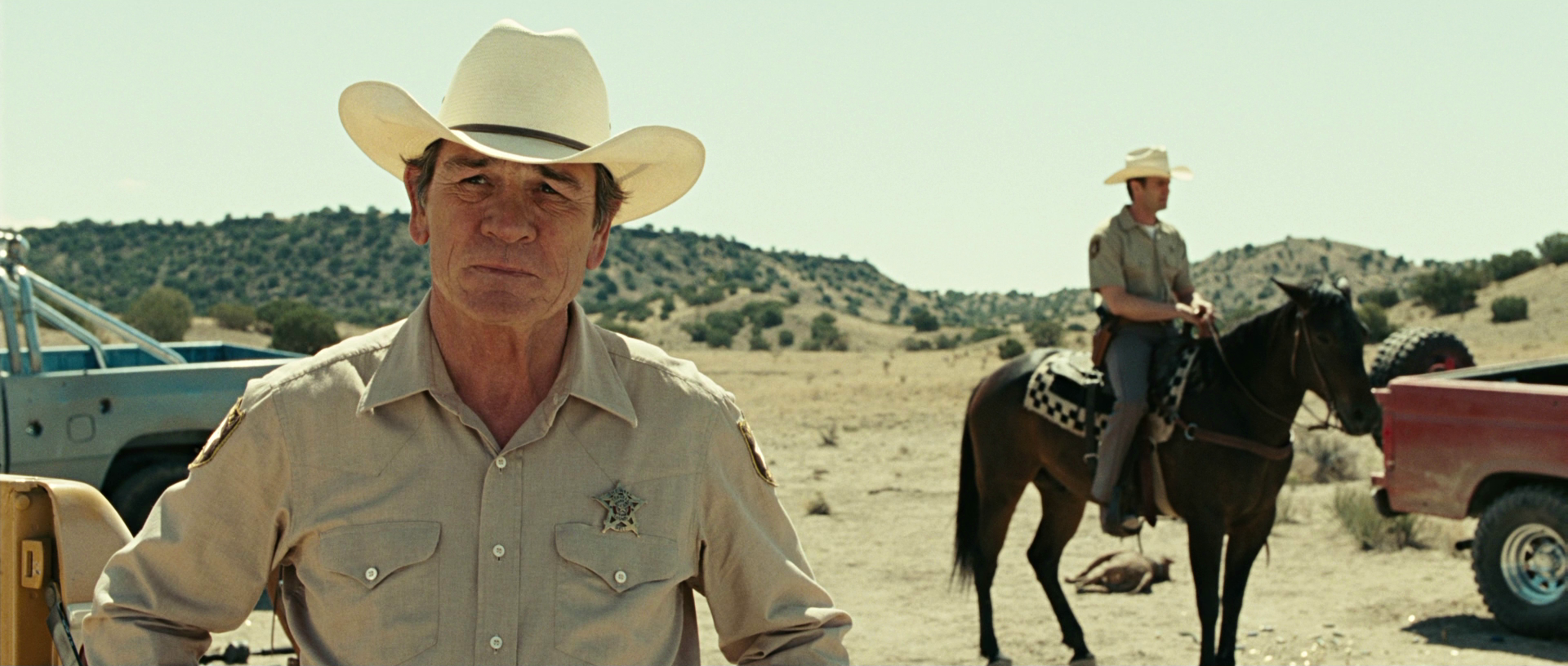

/Stasi Captain Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe) at his listening post in Das Leben der Anderen (The Lives of Others)

Speaking of omnipotent moral busybodies, this short piece in the Atlantic, which profiles the mission and struggles of the people monitoring podcast content at Media Matters and other listening posts, came to my attention yesterday by way of Alan Jacobs’s blog. Jacobs’s pithy commentary caught my attention. He confesses his surprise at two things:

(a) that to many Americans it now seems normal for people to devote hundreds of hours of their lives to listening to one podcast solely in order to find something, anything that can be used to shame the podcaster; and (b) that the people who behave in that way think their actions are politically meaningful.

I highly recommend reading the Atlantic piece, as it provides a uniquely open and unashamed profile of people who seem utterly unaware that they are colossal, thundering creeps. Devoting hours and hours to listening (at 2x speed, since they are not only creepy but lazy*) to podcasts they don’t like, carefully cataloging offenses, filing bullet-pointed reports to be used as political ammunition, struggling with a workload based on ever-growing mountains of raw material, hoping for laws requiring podcasts to be transcribed and indexed for greater “accessibility,” and congratulating themselves for tackling such difficult but important work, they remind me of nothing so much as the Stasi.

The Stasi (short for Staatssicherheitsdienst or State Security Service) was the East German secret police. Far more powerful, pervasive, organized, and effective than the underfunded and understaffed but more infamous Gestapo, by the time the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 the Stasi had vast, well-indexed archives covering the activities of over five million people, and one in four East Germans were working for them as informants.

But what reminded me of the Stasi wasn’t just the Atlantic’s subjects’ left-wing politics or their obsessive ferreting out of offense, but their work ethic—their startling willingness to do drudge work:

But going big and searching manually through the archives of any podcaster with a substantial back catalog requires not just time but motivation—an axe to grind, or at least an angle. “It was not a terribly glamorous reporting process. . . . It was not like what they show in the movies.” It was just sitting around listening to some guy talk.

I think it was that line that brought to mind the Stasi, and specifically the image of a small, quiet technician sitting in an attic, attentively listening—Stasi Captain Gerd Wiesler in the magnificent film The Lives of Others. In that film, pointedly set in 1984, Wiesler is assigned to watch playwright Georg Dreyman, a seemingly loyal Party man who has used the stage for dour dramatic messaging about the oppression of capitalism but whom the authorities now suspect of subversion. The film is thorough in its depiction of the bugging process, of the cataloging and reporting of every bit of potentially relevant minutiae (right down to “Geschlechtsverkehr,” sexual intercourse, in one report), of the horrible consequences for everyone, and, above all, the listening. Wiesler and others take long shifts in Dreyman’s attic, just listening, staring at the walls as Dreyman’s life plays out through their headphones.

For Wiesler, this ends up being not only transformative but redemptive, and depicting this transformation is the great power of The Lives of Others. But for the people in this Atlantic piece?

I doubt it. Part of my pessimism in this regard is the striking tone† of the report, both on the part of the subjects and of the Atlantic’s writer—not just reportorial, though it is an informative profile; not just approving, though the listeners’ work is treated as obviously legitimate and their struggles as obstacles that must by any means be overcome; but participatory. The author inserts a revealing parenthetical late in the piece:

(As a sometimes-listener of the chat show How Long Gone—they get good guests and they’re always laughing together!—I have imagined what it would look like to CTRL+F the entire catalog for all of the hosts’ weird comments about fat people.)

There you have it. This is the behavior of bitter exes, of forum trolls, of the weird kids we knew in high school who actually kept enemies lists. Though this piece seeks to portray its subjects’ work as legitimate owing to the heinous threat posed by Joe Rogan (whom I don’t follow and have intentionally avoiding mentioning before now) and his “misinformation”‡—or racial slurs, or transphobia, or “sexist comments,” or whatever—it becomes clear at this point that this industry of Stasi hirelings is driven by personal animus.

Which shouldn’t be surprising—especially if you’ve seen The Lives of Others, in which it turns out that the government’s suspicions of Dreyman stem from a bureaucrat’s obsession with Dreyman’s girlfriend.

I’d say I’m less worried about this kind of thing since Media Matters et al are private organizations and the Stasi was a government agency. But we’re learning more all the time about the way the US government is doing internet-age versions of the same things the Stasi did, but, thanks to technology, on an even vaster scale, and we’re also seeing how little the government needs an agency like the Stasi when powerful corporations and self-appointed case agents will do this work virtually gratis, and answerable only to the mob.

I don’t have a lot of conclusions to draw or solutions to propose, but I do hope a disgust with this kind of thing can grow sufficiently strong and widespread to drive it out of existence. I hope, but I’m not holding my breath.

In the meantime, you can learn more about the Stasi from books like Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall, and I can’t recommend The Lives of Others highly enough. Watch it if you haven’t, and think.

Notes, asides, and remonstrations:

*Also stupid. “‘He is the most popular podcast host in the world,’ Paterson told me. Yet few not in Rogan’s intended audience ever hear most of the things he says.” Congratulations, you’ve discovered how an audience works.

†Another revealing choice of words: “This is not to say that podcast fans are incapable of criticizing the voices they spend so much time with—only that they’re also prone to forgiveness.” Note that, here, forgiveness is a bad thing.

‡I’m struck that there is so much debate now about misinformation, disinformation, and even malinformation, but very little reference to truth.