Andersonville

/The real Andersonville, photographed from the stockade wall in mid-August 1864.

This year I set myself a goal of reading fewer but longer books, and to get the year started I decided to tackle a monster: Mackinlay Kantor’s 750-page, Pulitzer Prize-winning Civil War novel Andersonville. It took me exactly a month.

I first heard of Kantor’s Andersonville in the early 90s, when TNT aired its own Andersonville mini-series. Reviewers in the Civil War magazines I read condemned the mini-series for grossly exaggerating deliberate Confederate brutality, and compared it—unfavorably—to Kantor’s book, which they implied did the same thing. Both accusations, as it happens, are correct—for reasons I’ll get into—but I spent the next twenty-five years assuming Kantor’s book was a straightforward Yankee screed. Only in the last few years, when I discovered that he was also the author of a children’s book on Gettysburg that I had loved as a kid, did I first become mildly curious about, then genuinely interested in, and finally decide to read Andersonville.

I’m glad I did. Andersonville is a good book, if perhaps not a great one, and poses interesting questions for readers and writers of historical fiction.

The story of Camp Sumter

“Andersonville” is the popular name for Camp Sumter, a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp constructed in southern Georgia in early 1864. (The first prisoners arrived on this day 155 years ago.) Over its year and a half of existence, Andersonville received 45,000 Union POWs, who arrived by train from all theaters of war. 13,000 of them died.

Kantor sets out to tell the whole story of Camp Sumter. He begins with the land itself, exploring the woods and fields through Ira Claffey, a local planter whose three sons have all died in the Confederate army and whose plantation teeters on the edge of collapse through lack of manpower and cash. Ira meets a Confederate surveying crew looking for land for a new prison camp. They settle on a valley on the banks of Sweetwater Creek and construction begins. By the time the camp is finished and the prisoners have begun to arrive, we still have a good 600 pages to go.

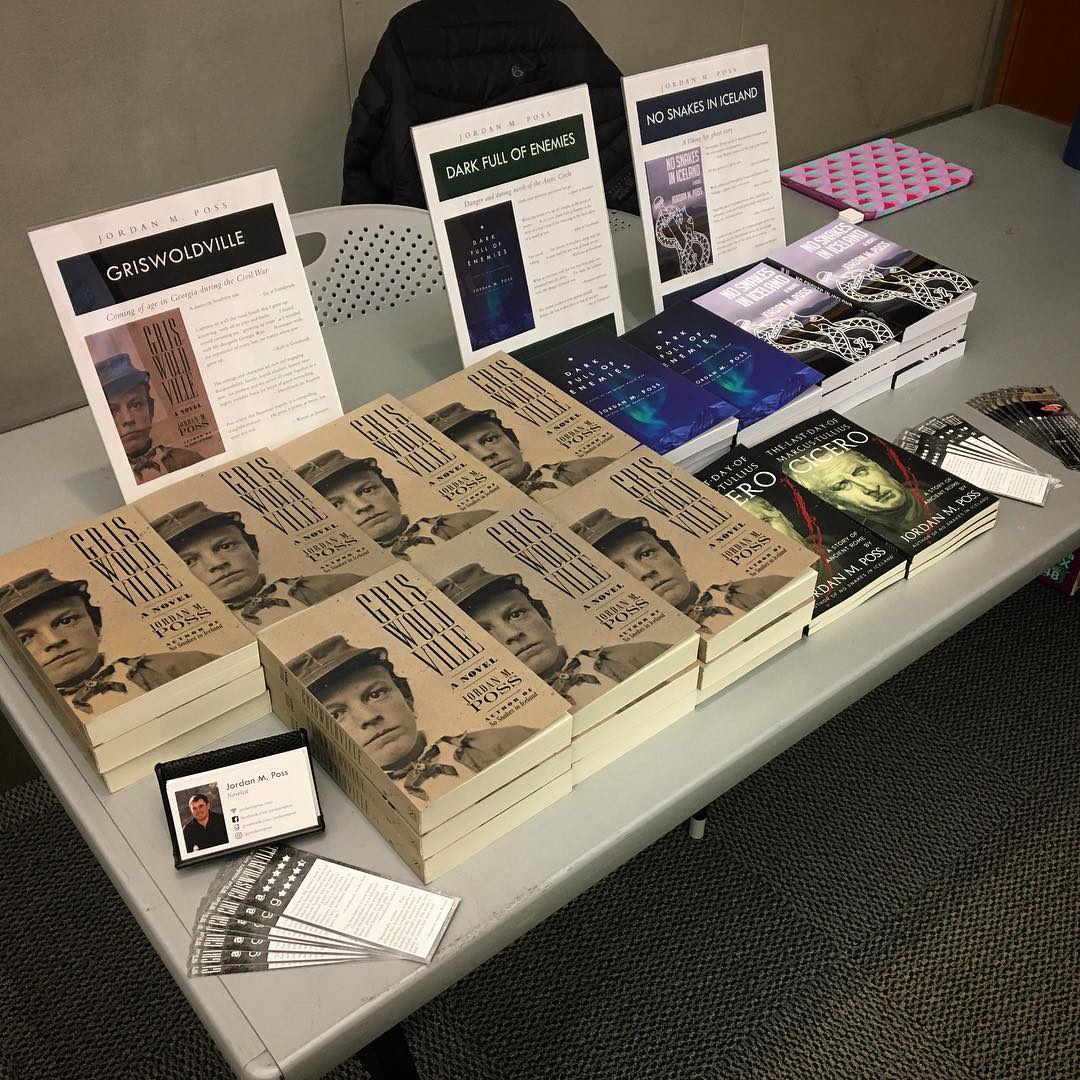

The novel excels in its narrowly focused sketches of incidental characters and the world in which they move. While Ira Claffey and his family’s losses frame the whole narrative, other characters flit in and out of the story—a white trash boy who joins the Georgia Reserves (just like Georgie in my novel Griswoldville) and becomes a guard; Captain Henry Wirz, the Swiss-born commander of the stockade; a local Presbyterian minister who tries to organize charitable donations for the prisoners; one of the camp surgeons; and many, many of the Union prisoners.

The prisoners’ chapters are particularly poignant, as they often give a prisoner’s entire life story up to his time in the camp. One harbors intense homesickness to get back to the German immigrant girl he fell in love with; another, having fled his intensely religious father, has become a prodigal son and falls in with the stockade’s villains; another has become deranged since his capture at Chickamauga and has turned informer for the Confederates, a status he comes to abhor; another is an Irish immigrant sailor trying desperately to dote on his underage boy lover; another, who learned criminality and murder at a young age in the immigrant slums of New York, gathers similarly cutthroat survivors to himself to form a gang; another, the scion of a privileged and worldly Jewish family, retreats inward, losing himself in prolonged reminiscences of his travels. Still others form pairs or trios, sometimes merely on the basis of having the same home state, to try to help each other survive. A few try to tunnel their way out, with tragic results.

And many historical figures—from the obvious Confederate officers like Wirz or his superior, General John Winder; to prisoners like Red Cap, a drummer boy who did clerical work for Wirz; diarists John Ransom and John McElroy; violent “Raider” William Collins; and Boston Corbett, a religious fanatic who, after his release, would become the man who killed John Wilkes Booth—wander in and out of the story. Even those characters that only appear for a single chapter are finely drawn, their life stories familiar, their fates worth worrying over.

The novel unfolds in an elephantine mid-century modernist style, a style that reminded me quite a bit of both Norman Mailer’s 1948 novel The Naked and the Dead and any number of William Faulkner’s books, if you can imagine that combination. Kantor is also interested in typically mid-twentieth century issues—nihilism, the meaninglessness of suffering, whether religion does or does not have anything to offer, and weird sex. He does not use quotation marks and his studies of the characters often freewheel into pure stream-of-conscious remembering.

It’s dense, it’s heavy, but the sheer accumulation of detail adds steadily to the book’s power. One comes to feel the world in which the novel takes place and to sense the immense variety of the people who live in it, of all the fully lived lives coming together in this particular place in southern Georgia. It’s powerful.

Unfortunately, it can also be punishing, something Kantor surely intended but that wears on the reader after a while. When one particularly prominent character is—apparently—shot at random by a guard, Kantor diverts us from his fate for a good twenty pages before revealing that, yes, he was killed instantly. Many of the deaths in the book, of young men wasted away to nothing by starvation, exposure, and diarrhea, moved me; that one felt like a cruel trick.

After the Raiders

Kantor also never entirely overcomes one particular narrative hurdle: What happened while all those prisoners were in Andersonville? Not much, honestly, and so large parts of the book depict people simply existing. Life in the camp was a continuous struggle, so there’s narrative meat there, but it drags in places, particularly once Kantor has finished with the most notorious incident in the camp: the trial and execution of the Raiders.

The Raiders were Union prisoners, many from New York City, who recreated the predatory gang environment of their urban slums and lived off of their fellow soldiers and prisoners through theft and murder. In response, a band of prisoners calling themselves Regulators tried to create a system of mutual protection and law enforcement and ultimately fought a battle with the Raiders. Having received permission from the Confederate authorities at the camp, a jury of recent arrivals—theoretically less biased—tried the Raiders’ ringleaders and their most violent enforcers and sentenced six to hang.

A true story, and a gripping one—right? Kantor capably dramatizes the incident with a steady drip of violence from the Raiders, futile resistance by the other prisoners, and a gradual increase in tension that finally explodes in the prisoner-on-prisoner war and the hangings. But the first batches of prisoners arrived in the late winter and early spring of 1864, and the Raiders were tried in July, making the Raiders’ run of the prison dramatic but short. With this out of the way, we’re still less than halfway through the camp’s history and only halfway through the book. The rest is good, but it never quite regains the narrative momentum of this solid third of the story.

In the end, relief finally comes for the addled, dropsical, hopeless prisoners when a large number are transferred to other camps in order to reduce overcrowding. General Winder, the general in charge of Confederate POW camps and the obvious villain of the piece, dies in South Carolina. The war nears its end. From here the story becomes somewhat unfocused, seldom revisiting Camp Sumter’s stockade and giving only the vaguest sense of how things end for a number of characters, finally concluding with the surviving Claffeys—defeated, returned to the United States once more—hiring on their former slaves as sharecroppers and watching the empty prison overgrow and crumble.

Character assassination?

Captain Henry Wirz (1823-65)

Andersonville was published in 1955, just ten years after the end of the Second World War. That conflict, in which Kantor worked as a war correspondent, looms over this novel in obvious ways. An overpopulated prison camp in which a third of the inmates, who arrived by rail, died of disease, starvation, and at the hands of guards—and commanded by a German-speaking officer in a gray uniform? At the end of the novel, when Union cavalry officers arrive to arrest Wirz at his home, a more or less explicit discussion of the Nuremberg defense occupies the conversation. Camp Sumter will always look a little different since Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, and Auschwitz joined it in the rearview mirror.

Kantor does depart from many of the immediate post-Civil War accounts of the prison by humanizing Henry Wirz—somewhat. He is a wildly exaggerated, hysterical, aggrieved man impotently trying to work out his frustrations, especially with a wounded arm that refuses to heal and a chain of command that gives him very limited real authority in his own camp. The result is his mismanagement of the prison, especially in times of prisoner unrest. Wirz’s immediate superiors, on the other hand, especially General Winder, are depicted as sadists intentionally trying to turn Andersonville into a charnel house and starve the Yankees—all propagandistic mischaracterizations originating immediately after the war.

The broader South, as seen through the Claffeys, is complicit as well. Their grief and bitterness at their terrible losses have seeded a deep desire to kill northerners at every opportunity. And though Ira Claffey in particular feels intense discomfort with the camp and the way honorably surrendered enemies are being treated, he and the others of his class are ultimately frozen into inaction by their ambivalence. And so the Yankees starve and waste away. Kantor explains Andersonville as the result of dark, archetypal resentments that somehow bring the cruelty of the camp into existence.

That makes for compelling literature but it doesn’t reflect reality and, thanks to the much wider readership awarded this Pulitzer Prize winner than any of the primary sources it was based upon, it has permanently skewed perceptions of Wirz, Andersonville, and what happened there. Subsequent dramatizations, including the TNT miniseries, have gone further. It is very difficult to watch that film version of Wirz without thinking of an unhinged Nazi commandant, a far cry from the pathetic figure in Kantor and the real person buried several layers down.

Good reading

So I finished reading Andersonville deeply conflicted. It is certainly a powerhouse of a novel, a modernist monument to what the written word can do in spinning whole lost and forgotten worlds into existence through an act of imagination, and its depiction of conditions in the camp, especially as the helpless prisoners weaken and die, is moving throughout—manifested as dread at the beginning of the novel, horror in the middle, and resignation and grief at the end. But it is also clearly a product of its time, obsessed with the things that preoccupied the post-World War II literary elite, and has only reinforced century-old myths and slanders about many of the people involved in the camp. As I wrote on Goodreads, “Four stars seems too low, but five is certainly too high.”

At Andersonville National Historic Site in December 2016

It’s a good book, but if you don’t want to invest the time and effort (literally—this book is a doorstop), check out William Marvel’s Andersonville: The Last Depot, an award-winning history published by Chapel Hill. Marvel includes all the major incidents dramatized in the novel, with special attention given to the Raiders, and assesses the charges eventually brought against Wirz at his trial, where he was convicted and hanged. It’s a well-researched, fair history of the camp from beginning to end.

Finally, nothing can substitute for a visit to the camp itself. I made the trek several years ago and have not forgotten it. Even the remoteness, a good forty minutes away from the nearest interstate, made an impression, and then there was the camp itself, with a few sections of recreated fenceline, the postbellum monuments, and the cemetery. If you’re interested in this topic, by all means read Kantor’s Andersonville, but make time to see the real place with your own eyes.