In Dilbert memoriam

/A childhood favorite. some of my interests have never changed.

I’m late to the game in memorializing Scott Adams, who died a week ago today, and can offer only a personal appreciation. I hadn’t kept up with him consistently for about twenty years and heard of him just often enough to be amused at what he was getting up to. When I heard of his terminal illness last year and his plans to seek assisted suicide, I was grieved.

But to begin in the proper place. I was a comics-loving kid and while I was aware of Dilbert, which came packaged with all my favorites in my grandparents’ Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Anderson Independent, I don’t know how often I actually read it. My fundamental sense of what comic strips were came from Peanuts, Calvin and Hobbes, and—for one-panel high strangeness—The Far Side. These are still the three highest peaks in my estimation of the form. Dilbert was of a different world and valence than these, and its subjects and artwork probably didn’t immediately appeal.

But sometime in the mid-90s I got a new classmate at my small Christian school. I already owe one lifelong debt to Clint because he told me about this short story he had read at his previous school, “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and accidentally introduced me to Poe, but he was also a huge fan of Dilbert. I remember him bringing a copy of Fugitive from the Cubicle Police—the politically correct title for what in the strip itself is referred to as the Cubicle Gestapo—to read between classes. His enthusiasm and the specific strips he shared with me from this book led me to look closer at Dilbert. It was soon a favorite.

It’s a testament to Adams’s genius that a couple of twelve-year olds could have found Dilbert’s workplace humor so funny. For us Dilbert was essentially fantasy literature, full of strange races and the vocabulary of forbidden tongues. I had no idea what HR was (those were the days) or what a consultant or software engineer did or what any of the office-specific jargon and tech lingo of the mid-90s actually meant, but we floated along on the vibes and characterization, inferring the meaning and import of jokes. Adams was very good at this. His skill with story, characterization, and the crucial timing of written humor meant our lack of experience of this world posed no obstacle to understanding—and laughing. We got the point even when we didn’t get the reference.

The chapter on office pranks was not especially helpful job preparation for a middle-schooler

Soon I had a respectable stack of Dilbert books, including one that worked as a key to Dilbert’s world and appealed to my Aristotelian love of taxonomy: Seven Years of Highly Defective People, a best-of sorted by character with notes by Adams in the margins. These were informative and funny and his personality came through clearly.

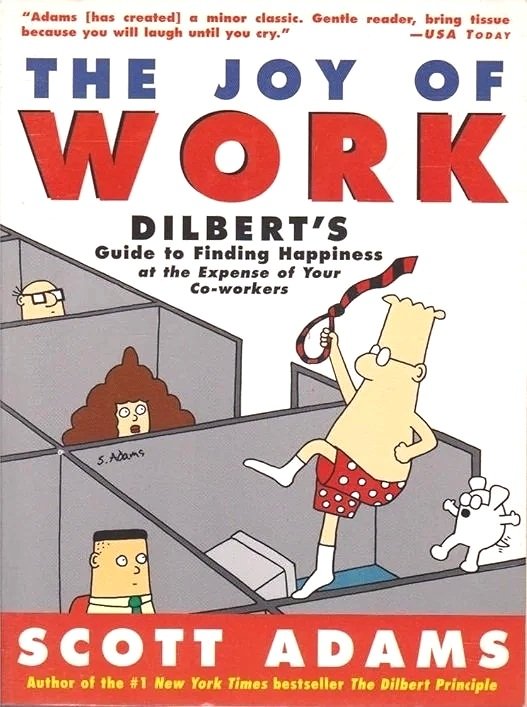

I got to know that better by signing up—again, this is still the mid or late 90s—for his e-mail newsletter, which automatically made me part of the DNRC: Dogbert’s New Ruling Class, the intellectual elite of his forthcoming new world order. Here Adams offered updates and commentary and responded to reader e-mails with a brimful serving of his wry snark. It was here, I think, or perhaps in The Joy of Work, one of his non-cartoon books on business culture, that I learned the word cynical.

I was in middle school by then (I remember reading The Dilbert Future on my first trip to Europe in 1998, not quite fourteen) and that’s a heady moment to be introduced to cynicism. Not that it wouldn’t naturally have occurred about that time, but I’m not sure learning that one could adopt a self-aware, sardonic, Olympian aloofness about one’s environment was helpful to me. I’m already bent, in Malacandran terms, in these directions anyway, and Dilbert encouraged me to adopt a more self-conscious and ironic posture strictly because it was funny. This cynicism was, ironically, quite naive.

Perhaps this would have been fine in a Sisyphean office environment, but at fourteen my environments were family, church, and school, fields where earnestness is actually warranted—most of the time. Because I learned cynicism as a way of humor about the same time I learned that, as a true believer, I would often be let down, I learned to use wry humor as a shield. I don’t think Dilbert did me any long-term damage but I’ve had to mature past these attitudes and habits.

Back to Adams himself and the DNRC. The Dilbert newsletter was probably my first experience of a writer opening up his mind to his readers. In addition to cartooning, the business world, and the vast intellectual superiority of his subscribers, Adams unironically flogged his vegetarian taco brand and his thought experiments—another phrase I learned from him. He shared a lot of the ideas he’d eventually package as God’s Debris. I may have been naive but I wasn’t suggestible and wouldn’t follow the funny man into woo-woo agnosticism. I had accidentally learned how to observe proper boundaries with people I liked but couldn’t agree with on the important stuff, a lesson I can take no credit for. It also won’t be the last appearance of grace in this story.

I kept up with Dilbert online through college—it was one of several strips I checked daily—but Adams himself, whom I admired as the off-kilter mind behind the cartoon, fell out of my awareness and I was content simply to read the strip. Somewhere between my undergrad and grad school years I lost the habit even of this, so it was a shock to run across it occasionally and see updates. Dilbert in polo and lanyard? That would have been unthinkable in 1998. (But guess what I wear to work every day.)

I have no opinion on Adams and politics. When he popped up on my radar over the last ten years saying contrarian things to the great consternation of a lot of people, I was unsurprised. Hadn’t y’all met him? He was a contrarian. If he hadn’t been, Dilbert would never have had the edge and absurdity that made it great. It would have been Cathy in a software company.

But to return to where I started, when Adams announced his imminent death from pancreatic cancer and his plans to end his own life, I was grieved. I remembered my mixed feelings about his dorm room-style philosophizing, his know-it-all pandeism, his air of superiority—in a word, his arrogance, a trait that attracts middle schoolers like a whirlpool attracts flotsam—and worried that his gifts would end in a final act of nihilism as dark as anything in Catbert’s HR department. What I did not do was hope or pray for him.

I am in no position to weigh the merit of Adams’s announcement of his conversion to Christianity just before he died last week. The various algorithms have tried to feed me a lot of videos—all with thumbnails of frantic, outraged people mugging in front of microphones—arguing yea or nay on his reasons. What I do know is that Adams was facing death, the ultimate argument-ender, and these podcasters are not, and that God is not willing that any should perish. In a history replete with sinners converting in the most miserable of conditions, how is God diminished by saving one more? What I felt when I learned of his decision, a Pascal’s Wager deathbed conversion, was relief and gratitude.

Again, these are my observations as an old fan who, after childhood, held Adams at arm’s length but always appreciated him. Dilbert’s peculiar sense of humor is a key middle-layer of the development of my own sensibilities, and Adams’s genius was the same as that that made Peanuts, Calvin and Hobbes, and The Far Side great—the ability to heighten the ordinary while keeping it familiar, to people his imaginary landscape with characters we recognize as our friends, family, coworkers, and ourselves, to make this hilarious, and to do it seemingly effortlessly. Also like Schulz, Watterson, and Larson, he was, for better or worse, uncompromising. That his complicated story and difficult personality ended with not just a turn toward grace but a casting of himself on God makes it all the more poignant.

Adams’s story seems to me one of eucatastrophe, of grace snatching victory from the jaws of defeat. It is not a story Adams would have written. Is there any better end for the cynic than redemption?