When authors throw shade at each other

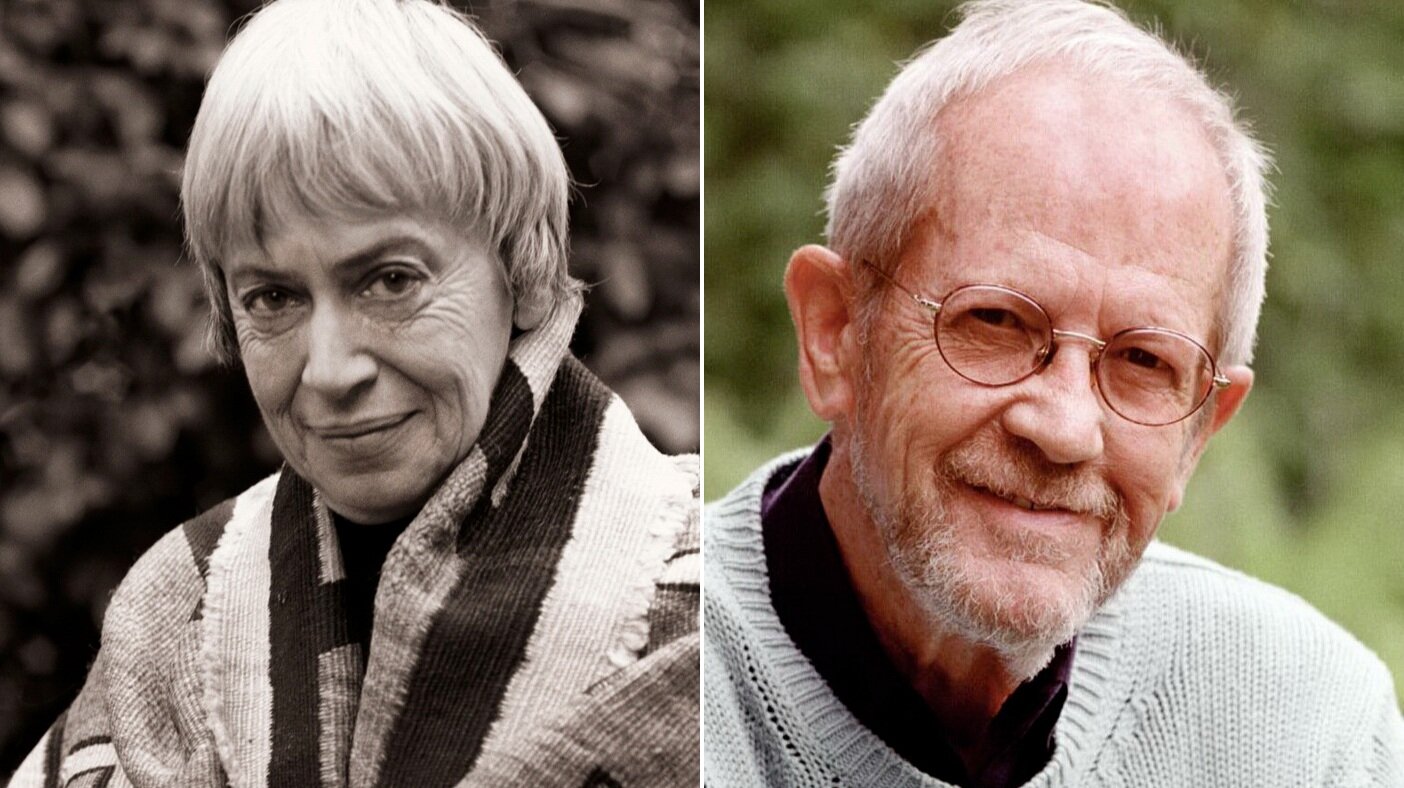

/Novelists Ursula K Le Guin (1929-2018) and Elmore Leonard (1925-2013)

Last month I read the sci-fi novelist Ursula Le Guin’s book Steering the Craft: A 21st-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story. It’s a brisk, delightful book of practical writing advice for those who already have some experience and are dedicated to refining the mechanics, the nuts and bolts, of their writing—hence her emphasis on craft. It was very good.

A small thing that caught my eye, especially coming in “An opinion piece on paragraphing” at the tail end of a chapter on sentence length and syntax:

“Rules” about keeping paragraphs and sentences short often come from the kind of writer who boasts, “If I write a sentence that sounds literary, I throw it out,” but who writes his mysteries or thrillers in the stripped-down, tight-lipped, macho style—a self-consciously literary mannerism if there ever was one.

This is an obvious dig at Elmore Leonard, an author of westerns and crime thrillers. I happen to be a fan.

In a famous 2001 piece in the New York Times titled “Easy on the Adverbs, Exclamation Points, and Especially Hooptedoodle,” Leonard published his rules for writing. There are ten. His rules include things like “Avoid prologues,” “Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue,” “Avoid detailed descriptions of characters,” and “Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly,” and at the end of his ten rules, Leonard includes another “that sums up the 10”:

If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.

LeGuin apparently interprets this as pretension, a phony posture of unmannered prose—as if Leonard is claiming to pick his sentences off a tree somewhere and do nothing to them. But it’s clear from the piece itself—and from the rule itself!—that Leonard too is talking about craft, about the rules he sets himself “to remain invisible” and how many tries it may take to achieve the desired effect. It takes conscious effort, something Leonard himself, who was unfussy about his craft and refused to make it mysterious in the manner of some writers (usually hacks), freely admitted. From an interview with Charlie Rose about the rules (and his short story collection When the Women Come Out to Dance):

Rose: A lot of people say that great writers never let their technique show. Does your technique show?

Leonard: Well, I say that my style is the absence of style. And yet, it is obvious, because people say they can tell by reading a passage that I wrote it. I mean when they read one of my books they know it’s my book and not someone else’s book.

Rose: Is that good?

Leonard: Sure. I think it’s good.

Rose: Because it has a certain… style, a certain zing.

Leonard: Because it has a certain sound. Whether it’s a zing or… I think of style as sound.

Leonard goes on to describe how a writer’s sound originates in his attitude, which brings to mind LeGuin’s accusation that Leonard writes in a “macho style,” something I’ve seen repeated elsewhere. I’ve read a bunch of Leonard’s novels now and honestly can’t say where this comes from. My sense of his narration is that it is terse, detached, and matter-of-fact; masculine perhaps, if we’re going to have this argument about omniscient third person narration, but by no means the bro-ish tough guy grunting that LeGuin implies.

(And for what it’s worth, Leonard has written a lot of compelling female characters. Read Out of Sight and Rum Punch for two of them. Both were adapted into films with strong female leads.)

A final thing about Leonard’s rules, and something I’ve noted here before, is that everywhere Leonard wrote or talked about his rules he made it clear that they were his rules. They were not for everybody. In the opening paragraph of the New York Times piece he writes that

If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over.

This is a pretty weak and genial “boast,” especially considering the number of counterexamples—Tom Wolfe, Jim Harrison, Margaret Atwood, and others—he offers in the same piece, often immediately following one of his own rules. One of the things I’ve enjoyed about listening to Leonard in interviews is his straightforwardness about his work and his self-effacing attitude about it. I think that bespeaks a humility about his craft that comes through in that most difficult piece of advice to give—What works for me works for me and might not for you. Do what works.

So is LeGuin’s criticism fair? No. It’s strikingly uncharitable. But it got me to revisit a favorite writer and really pore over his advice, and made me appreciate it more—which also made me appreciate her book more. Because even with this short, one-paragraph jab LeGuin offers much of the kind of advice I think Leonard would have appreciated, too, and much of it comes down to that difficult piece of advice above.

More if you’re interested

Steering the Craft was very good. You can find it on Amazon here. The New York Times sometimes paywalls Leonard’s original piece; you can also find almost all of it here—with a delightful illustration of the opening scene of Freaky Deaky—or the rules themselves at the Guardian here. You can also buy the article as a lavishly illustrated hardback gift book. By all means read the older blog post I linked to above, in which I compare Leonard’s rules with those of George Orwell and CS Lewis and find some helpful commonalities. And I highly recommend watching Leonard talk through his rules in some detail here.