Doing the book-ban shuffle

/Over the weekend I took my sons to an old-fashioned barbershop for haircuts and a glass-bottled Coke. I also introduced them to a joy I had almost forgotten—the old-fashioned comics pages (“funnies,” as my granddad called them) in an old-fashioned Sunday newspaper.

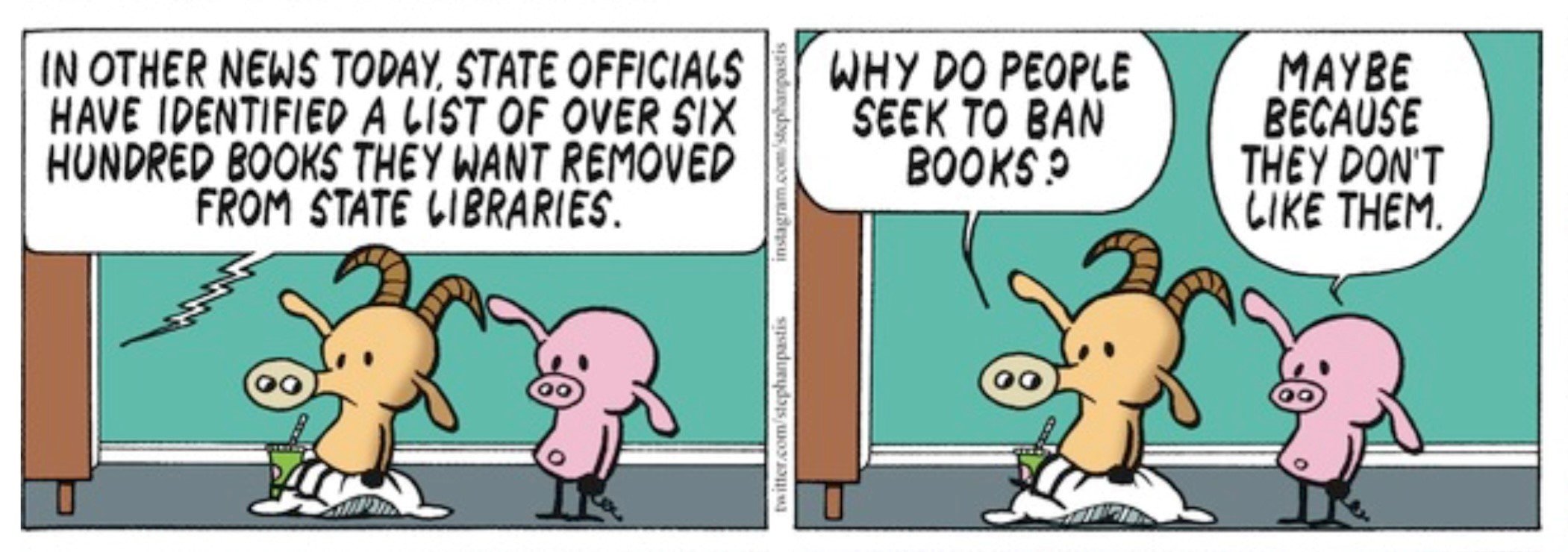

Something that was not old-fashioned was the theme of Sunday’s “Pearls Before Swine,” one of my favorite daily strips when I was in college. Here are the two opening panels:

Notice the little definitional shuffle from panel one to panel two. The news anchor mentions books being removed from libraries. Goat asks about banning books.

These are not the same thing.

Naturally, “Pearls” being “Pearls,” contemplation of the purported danger of certain books is just a clever setup for an absurdist subversion at the end. Read the whole strip for a good laugh. But precisely this imprecision—the confusion of bans and censorship with local decisions about what is and is not on the shelf of a library—is endemic now.

Alan Jacobs had a good post on this subject back in the fall, when there was an epidemic not of books being banned but of self-regarding people congratulating themselves on their superiority to the imagined reactionary troglodytes who want books banned. (Look at the comments section on that “Pearls” strip for a representative sample. Everyone seems to know that it’s precisely the people they don’t like who are the worst about this.) Responding to just such an essayist who had boasted of her habit of “intentionally purchasing and reading books that are banned” and who linked to a list of such books, Jacobs wrote:

The problem here is that none, literally not one, of the books on the list [she] links to have been banned. Neither have they been “censored,” which is what the article linked to says. That’s why [she] can buy and read them: because they’ve been neither banned nor censored.

What has happened is this: Some parents want school libraries to remove from their shelves books that they (the parents) think are inappropriate for their children to read. You may think that such behavior is mean-spirited or otherwise misconceived—very often it is!—but has nothing to do with either banning or censorship.

This is partly pure linguistic sloppiness—the same problem that causes people to treat the words racism, bigotry, and prejudice as interchangeable. Sloppiness is bad enough, but it also proves advantageous to people who may know better but have political axes to grind. So when one mom complains about books in a local school library and the school decides to retain them, partisans can claim the governor of that state—who is otherwise entirely unrelated to this local non-story—is personally banning books and who does that remind you of?

Notice that that Snopes article I linked to still does the little book-ban two-step at the end by invoking a supposed “rise” in “censorship” in the state in question, though. More on that below. But Jacobs’s point stands. Here’s more from him:

In a sane world, the term “ban” would be reserved for books whose sale and circulation are illegal in some given place, and “censorship” would refer to the removal, by some legal or commercial authority, of certain portions of a text or film or recording. (I say “commercial” authority because sometimes companies that own the rights to works of art decide, without legal pressure, to delete some lyrics in a song or change certain words in a book.) But thanks to people who want to smear their RCOs [Repugnant Cultural Others], it is now common to use precisely the same words to describe (a) what the nation of Iran did to Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses and (b) a polite letter from a parent to a school librarian asking that books that offer anatomically detailed descriptions of sexual practices not be readily available to third graders.

As it happens, there is actual censorship of the kind Jacobs describes happening in the United States, but it’s not much-hated state governors pushing for it. And what do you know? Here’s a book that has been removed from sale by a serious commercial authority. But somehow I don’t see the people who buy “Fight Evil, Read Books” totes lining up to demand a copy.

Jacobs concludes with what should be an indisputable statement of truth: “This failure to make elementary distinctions is neither politically nor intellectually healthy.” But as long as this kind of sloppiness remains politically advantageous there will be no incentive to correct it. None.

Regarding the much-commented upon “rise” in censorship, bans, or whatever you want to deceptively call them, the ALA, which has proven adept at political axe-grinding, has helped manufacture this impression, dangling the specter of hillbilly theocrats banning Maus or whatever. (Speaking of manufactured, deceptive stories that became opportunities for virtue signaling.) Jacobs links to two detailed and helpful posts on the ALA’s “book ban paranoia” from Micah Mattix. The salient fact from Mattix’s reporting:

The 20% figure [a reported 20% increase in “challenges” to books in libraries] concerns the number of unique titles, but the actual number of requests to censor is only up by 14—from 681 in 2022 to 695 in 2023. That’s right. Across nearly 120,000 libraries, which serve millions of students and patrons, 14 more requests to censor have been filed.

Check out Mattix’s posts here and here.

The problem with all these book bans is that no one is banning books, and very, very few people even want to. We need to stop talking like it.