Summer reading 2025

/My reading has tipped more toward fiction than non-fiction for the last couple years, and this summer may be the most fiction-heavy season yet. I try to read at whim, but I plan to correct that a little this fall. I have a lot of good history and biography sitting around, waiting. In the meantime, I enjoyed a lot of good books this summer, and the following—presented in no particular order—are my favorites. As always, I hope y’all can find something here to enjoy.

For the purposes of this blog post, “summer” runs from mid-May to Labor Day. And, as usual, audiobook “reads” are marked with an asterisk.

Favorite fiction

The Cannibal Owl, by Aaron Gwyn—A short, beautifully written Western novella based on a real person, an orphan boy taken in and raised by Comanches who nevertheless becomes their destructor. This story defies easy summary but is totally absorbing and breathtakingly dramatic. One of the rare short books I’ve actually wished were longer.

A Deadly Shade of Gold, by John D MacDonald—An old friend of “salvage consultant” Travis McGee pays a visit after several years’ absence and shows him a solid gold Aztec idol. He also asks McGee to set up a meeting with Nora, the girlfriend he unceremoniously abandoned, and is unceremoniously killed. In the aftermath, Nora hires McGee to investigate the provenance of the idol, where the rest of the treasure his friend mentioned has disappeared to, and who had him killed. McGee, eager to avenge his friend, travels to luxury villas in Mexico and the estates of pervy millionaires in California and gets entangled with the illicit antiquities trade, killer guard dogs, multiple women, and Cuban exiles along the way. Gripping throughout.

Judgment on Deltchev, by Eric Ambler—Ambler’s first postwar novel. A British playwright is recruited to report on the Stalinist show trial of a leftwing anti-Communist in an unnamed Eastern European state just after the end of World War II, as the Iron Curtain falls and Soviet puppet governments consolidate control and eliminate rivals. Intricately plotted and, unfortunately, all too realistic. Full review on the blog here.

The Schirmer Inheritance, by Eric Ambler—Ambler’s second postwar novel, a legal thriller in which American lawyer George Carey attempts to find the heir to a fortune with tangled roots the Napoleonic Wars. The last surviving descendant of a Bavarian soldier who deserted following a battle against Napoleon has died intestate, and before the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania seizes the inheritance they must first confirm that there are no other potential heirs. As it turns out, there may be one—a German soldier who went missing in Greece near the end of World War II, but hasn’t been confirmed dead. Carey must either him or confirm that he was killed by guerrillas. His search will take him across Europe and closer and closer to danger. I read this one before Judgment on Deltchev, and while that is clearly the superior novel, The Schirmer Inheritance offers a solid, atmospheric slow-burn and the vintage Ambler pleasure of a glimpse into a complicated, unsettled, dangerous underworld.

The Looking Glass War, by John Le Carré—After a British agent retrieving a canister of film is run down by a car in Finland, the small, understaffed, impotent agency behind him attempts to run an infiltration operation in East Germany. The followup to The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, which Le Carré—somehow—feared made espionage look too glamorous and exciting, this is a story of confusion and futility. Be prepared for that. It sags just a bit in the middle but has exceptionally gripping opening and closing chapters. Le Carré at his best still astonishes me with how effortlessly his novels read.

The Properties of Rooftop Air, by Tim Powers—A powerfully creepy novella set in the subterranean world of Regency London before the events of The Anubis Gates, which I read this spring. A satisfying and meaningful self-contained story.

The Oceans and the Stars, by Mark Helprin—A subtle and clever Odyssey for the age of presidents (instead of gods) and terrorists (instead of monsters). A US Navy officer in a dead-end career oversees the construction of a last-of-its-class small ship, and falls in love with a lawyer whose husband has abandoned her. His daring and courage and her commitment will be tested when he and his new ship, the USS Athena, deploy to the Indian Ocean to fight Iran, Somali pirates, and ISIS. Full review on the blog here.

Favorite non-fiction

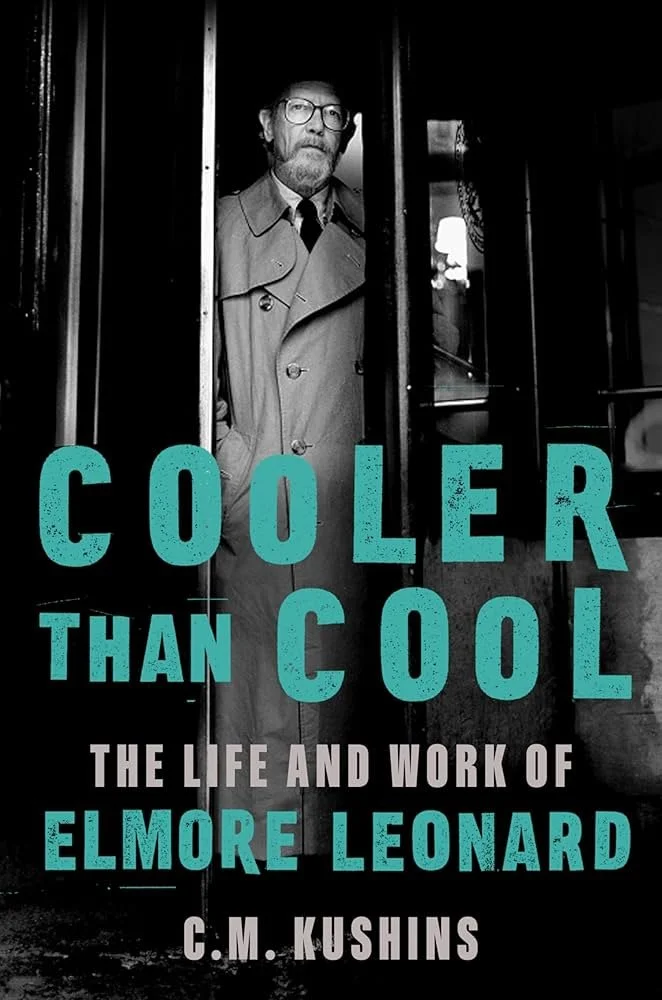

Cooler than Cool: The Life and Work of Elmore Leonard, by CM Kushins—After Nicholas Shakespeare’s recent Ian Fleming biography and an older Poe biography back in the spring, I read two more big literary bios this summer, both new. One I had been anticipating, but this one, a new authorized biography of Elmore Leonard, was a great surprise. I learned about it only the week before it was published, and was gifted a copy by the publisher. It’s excellent—a comprehensive cradle-to-grave account that pays close attention to Leonard’s life, career, and craft. I especially appreciated the latter: Kushins notes key influences on Leonard’s imagination and writing at different stages of his life (especially crucial: All Quiet on the Western Front as a boy, For Whom the Bell Tolls as a young writer, The Friends of Eddie Coyle just as he pivoted from Westerns to crime) as well as his writing process. The book is also full of delightful stories: Leonard the Seabee sending coy letters to an old friend from the South Pacific, Leonard the ad man writing longhand in his desk drawer at work, Leonard, in mounting frustration, working on film adaptations with the mercenaries and prima donnas of Hollywood. The one area I wish were covered in more detail is the personal. Kushins pays close attention to the young Leonard’s devout Catholic faith but, though we sense a change comes during his divorce in the early 1970s as well as his struggle toward sobriety, why he ended up agnostic is left unclear. That said, the otherwise solid coverage of his life and the thorough attention to his work is wonderful.

Sidney Reilly: Master Spy, by Benny Morris—From Yale UP’s Jewish Lives series, this is a short biography of the Russian-born Sigmund (or possibly Solomon) Rosenblum who, as Sidney Reilly, spied off and on for the British before becoming a professional agent during the First World War and committing himself to the defeat of Bolshevism. This is an extraordinarily complicated story with lots of points of confusion, myth, and missing information, but Morris tells it well. There are longer biographies of Reilly out there, which I am going to seek out, but this offered a solid introduction to a tumultuous life.

Edgar Allan Poe: A Life, by Richard Kopley—The other of the two big literary biographies I read this summer, Kopley’s Edgar Allan Poe is comprehensive, sweeping, exhaustively researched, and combines a thorough account of Poe’s life with criticism of his work. Kopley demonstrates mastery of both, but has not grown too close to his subject; though charitable, especially toward Poe’s drinking and his feuds with other authors, which to some biographers smacks of jealousy or mere trolling, Kopley is not uncritical. He is especially good on Poe’s personal relationships, not only his fraught relationship with his foster father John Allan and his doomed wife Virginia, but also his friendships with other writers, childhood friends from Richmond, and the various women he loved both before and after Virginia. Kopley’s literary criticism is also insightful and thought-provoking. Though some of his interpretation is perhaps too autobiographical for my taste, I benefited greatly from his emphasis on structure and allegory, especially in Poe’s early work. This is probably the most thorough life of Poe that I’ve read, but is also probably too long and detailed for the casual Poe fan. But for anyone with more than passing interest in the subject I highly recommend it.

Julius Caesar: A Biography, by John Buchan—A succinct overview not only of its subject but of his life and times, with a special concern for the decline and collapse of republican institutions. See below for a link to the full John Buchan June review.

John Buchan June

This year for John Buchan June I emphasized Buchan’s short fiction, reading three collections of stories. I also read one of his short biographies and three novels, including his first full-length historical adventure. Here are all eight of this year’s reads, each linked to the full review here on the blog, in order of reading:

The Runagates Club (1928)

John Burnet of Barns (1898)

Julius Caesar: A Biography (1932)

The Watcher by the Threshold (1902)

A Prince of the Captivity (1933)

The Courts of the Morning (1929)

The Path of the King (1921)

Of these, The Path of the King, particularly its early stories set in the Middle Ages, may be my favorite, though “No-Man’s-Land” in The Watcher by the Threshhold is a stellar bit of creepiness. Of the full novels, I think the early, flawed, overlong, but hugely enjoyable John Burnet of Barns was my favorite.

After four years of this event I’m running low on Buchan novels but there’s more short fiction and I’ve barely touched his biographical work. Looking forward to next year!

Rereads

Reading Cooler than Cool got me to revisit a few of my favorite Elmore Leonard novels on my commute. I’d recommend any of these. And though I’m not sure how many times I’ve read The Hobbit, this is my second time through with the kids. A joy.

Mr Majestyk, by Elmore Leonard*

Hombre, by Elmore Leonard*

Freaky Deaky, by Elmore Leonard*

The Hobbit, by JRR Tolkien

Looking ahead

I’m glad to say I’m already well into a couple of good reads for the fall, including Michael Palma’s recently published terza rima translation of my favorite book, The Divine Comedy, and I have a lot of classics lined up. I’m sure you’ll hear about some of them in the end-of-year recap. In the meantime, I hope y’all will check some of these out, and thanks as always for reading!