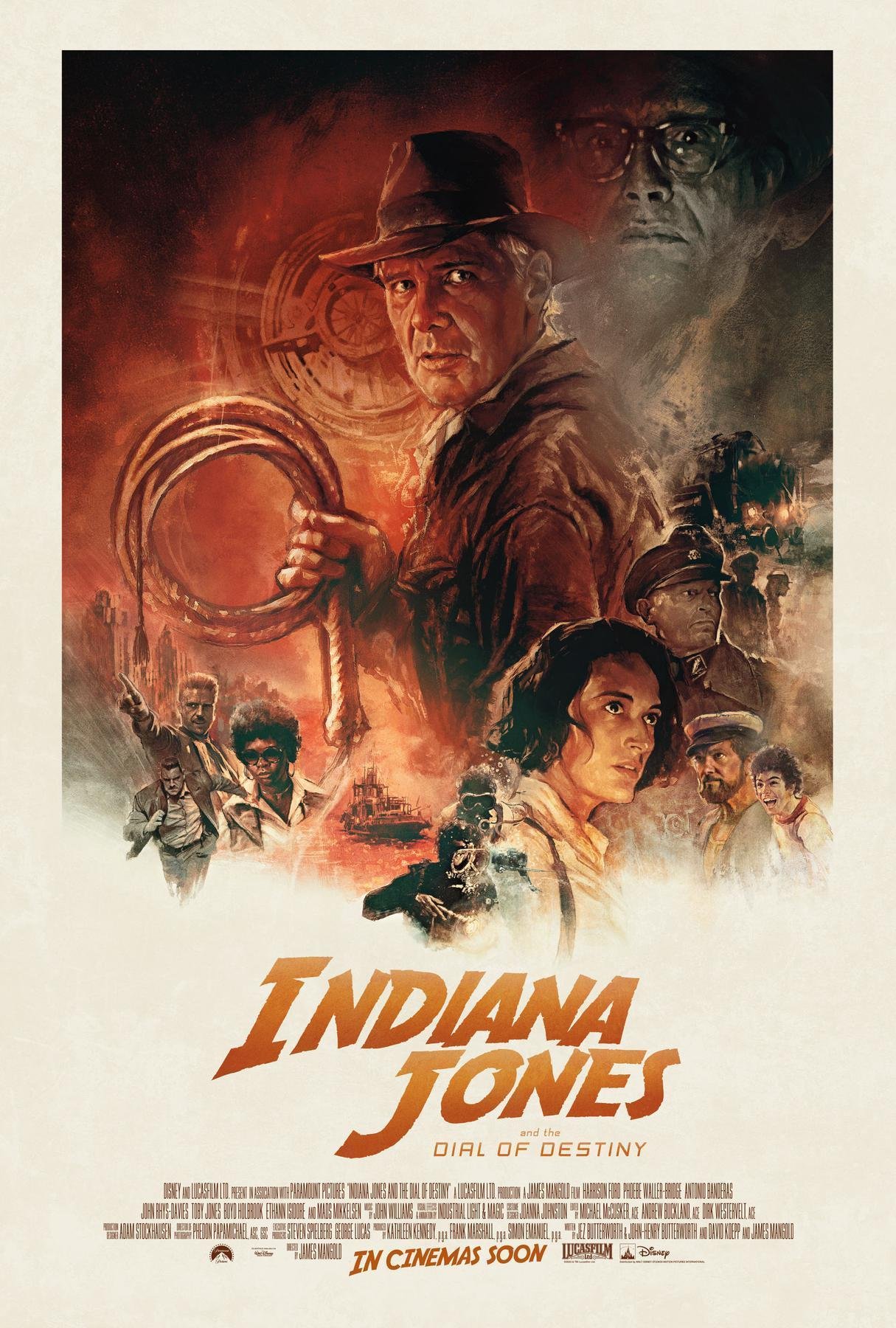

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny

/Last night my wife and I started my Independence Day break off right with an impromptu movie date. I was much more excited about the date than the movie—Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. After the debacle of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, the prognostications of various internet types, and Disney’s track record using and abusing Lucasfilm characters, I had well-founded suspicions that it wouldn’t be very good and was hesitant to see it. But I’m not going to miss an Indiana Jones film and my wife and I really needed to get out of the house, so off we went.

Fortunately, Dial of Destiny turned out to be better than I expected. That might not sound like a ringing endorsement, but in the present filmmaking landscape I’ll take it.

It’s not the years

After a prologue set in 1945, as the Germans withdraw from southern France with a trainload of looted antiquities, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny picks up in the summer of 1969. Indy is old, tired, separated from his wife Marion, and set to retire from the downtown Manhattan university where he lectures unenthusiastically to uninvolved students. (One sympathizes.) When he receives a visit from his goddaughter Helena (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), child of an old colleague in both the academic and military intelligence worlds, he is drawn into a pair of interlocking schemes involving an ancient artifact called the Antikythera—a sophisticated golden mechanism of unclear purpose supposedly built by Archimedes himself. Only half of the device is known to exist. Helena wants Indy’s help finding the other half.

The other scheme is that of Professor Schmidt (Mads Mikkelsen), a German émigré physicist who helped put Apollo 11 on the moon. Schmidt, an alias for Jürgen Voller, whom Indy first encounters in the prologue, also wants the complete Antikythera and will go to violent lengths to get it. Why? Who is he working for?

As it turns out, Helena wants the device because she has been hawking antiquities on the black market and Voller wants it because he believes it can detect and open “rifts in time,” making actual time travel possible. Examination of Helena’s father’s notes on the device suggest that, should Voller acquire it, he will use it to travel to the weeks just before the Nazi invasion of Poland. The question, again, is Why? But the possible answers are much darker than Indy cares to consider.

I won’t recap the plot in any greater detail. The filmmakers do a good job following the classic Indy formula while also including some genuinely fun and surprising new stuff, and I don’t want to spoil anything.

It belongs in a museum

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is a mixed bag, but fortunately the mixture is of the good and the only so-so rather than the so-so and the bad of the last film.

To my surprise, I actually liked the late 1960s setting and thought the filmmakers used it well, especially in setting up a link to the classic Indy antagonists, the Nazis. (It’s unstated in the film, but presumably Voller was brought to the US and put to work in rocketry under the auspices of Operation Paperclip. Look it up.) Mads Mikkelsen plays Voller wonderfully, using his natural intelligence and gravitas and menacing looks to great effect in perhaps his second best villainous performance after Le Chiffre in Casino Royale. His purely pragmatic scientism makes an interesting counterpart to his rival antagonist, Helena, who is interested only in money. Both have a purely instrumental view of the past—both seek to use the Antikythera. Indy, in his love for the past and desire to preserve it for its own sake, is the solution to these mirror-image sins against history.

Further, the small role played by Sallah (John Rhys-Davies) and a few other classic Indy characters was well-informed by history and didn’t feel like pure fanservice. The writers have allowed things to happen to the characters between films, something missing in a lot of recent sequels.

More importantly, Dial of Destiny better evokes the feel of classic Indy than Kingdom of the Crystal Skull ever did. Two sequences in particular stood out to me. The first, a diving sequence to a Roman shipwreck in the Aegean, was something new and inventive—like a cross between Indy and Clive Cussler—and resulted in a fun and exciting scene. The second, Indy’s exploration of caves leading to a long-lost burial chamber, was perfectly executed, capturing the suspense, wonder, and danger of the cobwebbed tunnels and musty tombs in the old films. It had more than a little of the opening of Raiders and the climax of The Last Crusade in it while also standing on its own.

Part of evoking the feel of classic Indy depends upon John Williams, now 91 years old, who composed the score for Dial of Destiny. Williams uses old leitmotifs to set the mood and give depth to the characters without indulging in pure nostalgia and also incorporates some new themes. It’s a very good score. Stay during the closing credits for one of Williams’s signature powerhouse brass compositions.

(Here I’ll issue my one spoiler warning—skip the following paragraph if you haven’t yet seen Dial of Destiny.)

Perhaps what most impressed me about the film was that it surprised me. Once the Antikythera has been rebuilt and Voller travels into a time rift, flying through a thunderstorm and out into bright Mediterranean sunshine, I was actually excited—I had no idea what was about to happen and couldn’t wait to find out. And what happened was so batty I loved it: Voller, deceived by the device, has flown into the Roman siege of Syracuse in 212 BC and, when his plane crashes on the shore, Indy and Helena meet Archimedes himself. (For a minute I was worried they would witness his death.) Unfortunately the sequence drifted into the grandfather paradox stuff I find so lethally dull in time-travel stories, but the excitement and fun of this climax were genuine pleasures.

(Spoiler-free resumes here.)

Digging in the wrong place

But Dial of Destiny also has a lot of weaknesses. It is too long and too slow, something that could never be said of the originals. For about the first hour after the prologue, the film galumphs from sequence to sequence. Much of this half of the film has the feeling of rewrites and studio interference, as if—to use an archaeological metaphor—there are fragments of previous Dial of Destiny scripts littering our dig. Antonio Banderas, for example, who plays the captain of the diving ship that takes Indy to the Roman shipwreck, is woefully underused.

By the time of the frogman sequence the film’s pace evens out, but the early going has a lot of awkwardly structured exposition and overlong chase sequences. These are also burdened with some dodgy CGI, not much improved upon from what you see in the trailers.

Speaking of CGI, the digitally de-aged Harrison Ford of the prologue is only convincing part of the time. Sometimes it looks good, but more often, especially in closeups, he has the uncanny valley look of Rogue One’s Grand Moff Tarkin or Robert Zemeckis’s misbegotten motion capture films. More distractingly, despite the obvious effort put into the de-aging, Ford sounds and moves like an elderly man.

As much as I love Harrison Ford, his age is a problem in the film. He looks feeble and rheumy-eyed, moving with the gingerly care of the retiree even when he’s supposed to be neck-deep in adventure, and it’s hard to take it seriously when he punches or outruns much younger characters. The writers make good use of his age in a few places—for example, in a climbing sequence in which Indy grouses about his many, many past injuries—but his fighting and chasing and the way he absorbs punches and even a gunshot are just not believable, even by the standards of Indiana Jones.

There are also some underdeveloped ideas that could have strengthened and deepened the story. The contrast between Helena and Voller should have cast Indy’s purer love for the past into sharper relief, but once the action gets going these themes are left unexplored. Further, the supernatural is pooh-poohed early in the film, an attitude that is allowed to stand. In this Indy, there is no supernatural dimension, only mathematics. Philosophical materialism and post-Newtonian physics is a strange place for an Indiana Jones film to land, but here we are.

Finally, the conclusion is weak. Nothing can beat the perfectly calculated ending of Raiders or the classic Western homage at the end of The Last Crusade, but Dial of Destiny whiffs. For one, Helena, a criminal who operates on purely selfish and acquisitive principles throughout the film, skates by consequence-free when what she needs is an Elsa Schneider fate. She gains some redemption at the end, but her past conduct, especially her manipulation of Indy, feels like a thread left hanging.

Further, in trying to resolve Indy’s relationship with Marion, the writers finally and totally cave in to nostalgia. This final scene is well executed, but I found myself rejecting what I was feeling because I knew I was being manipulated. It’s a strange, Up-like note with which to end the story of one of cinema’s greatest action heroes. After the final iris out—an oddly comic effect—but just before the credits began, I actually wondered if there would be more. But there wasn’t—no government warehouse, no ride into the sunset.

Conclusion

All that said, I’m glad I saw Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. As I wrote at the beginning of this post, I was surprised how much I enjoyed it. It offers several genuinely fun and exciting action sequences in the best Indy tradition. But it is also overlong, awkwardly paced, and tries too hard to craft a loving sendoff for a character who needs no introduction and wouldn’t want a long, tender goodbye either.