Further notes on the term Anglo-Saxon

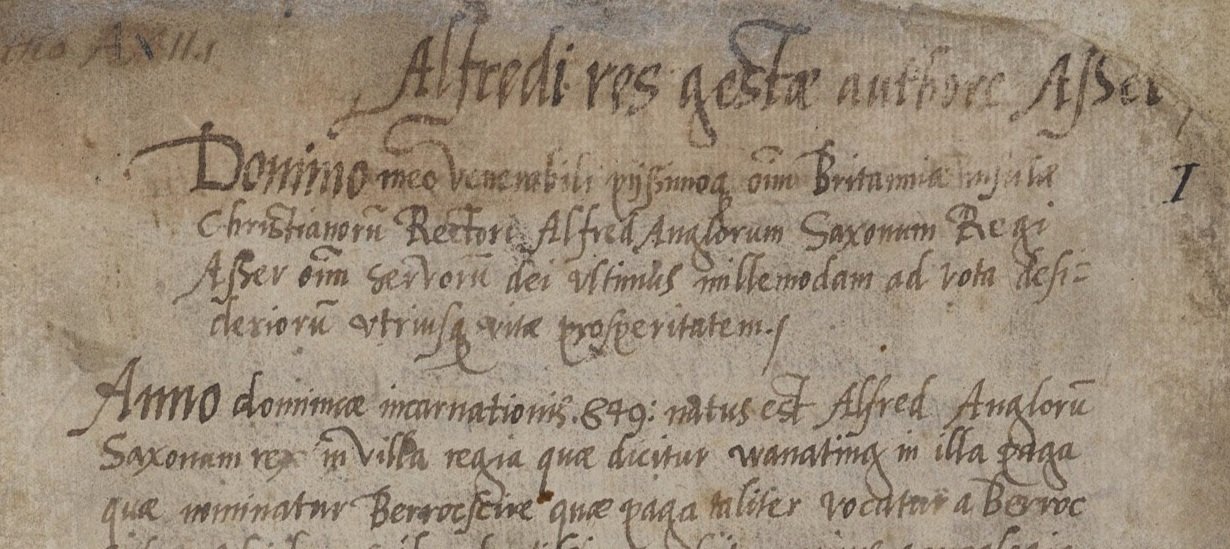

/The first page of a 16th-century manuscript copy of the Welsh priest Asser’s 9th-century Life of King Alfred in the British Library. The term “King of the Anglo-Saxons” is visible in two places on this leaf.

Late last year I finally got a long-gestating post on the term “Anglo-Saxon” into writing. For several years now, a cadre of leftwing academics has striven to purge the disciplines of medieval history and literature of the term on the specious grounds that it is either racially loaded or straightforwardly racist. I disagree strongly, and set out my reasons why—with an assist from Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook—in that post. You can read that here.

Earlier today the cover story The Critic’s June issue went up on the magazine’s website. Titled “Anglo-Saxon extremists,” it’s an essay by Samuel Rubinstein that covers some of the same ground and makes similar arguments as mine from last year, including the intellectual sleight of hand required to make anti-Anglo-Saxon arguments plausible and even some points regarding the intense racial neuroses that seem to be my country’s chief export nowadays. Rubinstein also helpfully digs into the genesis of the controversy, which has mostly been stirred up kept going by a small number of academics with ulterior motives. A few choice excerpts:

On the cultural chasm separating British perceptions of the term from those of the rare American who has even heard it:

“What are you studying at the moment?”, an American student asked me once, as we ambled back from a seminar. “The Anglo-Saxon paper.” She gave me a disapproving look, told me she was more into “global history”, and mumbled something about “WASPs”. I wondered what St Boniface or St Dunstan might have made of the “P” in that acronym.

From this interaction I learned of an important cultural divide. Insofar as Americans encounter “Anglo-Saxons” at all, it is in this “WASP” formulation. When Britons encounter “Anglo-Saxon”, meanwhile, it is in Horrible Histories, Bernard Cornwell, or Michael Wood on the BBC. The Anglo-Saxons appear to us as a benign link in the chain of Our Island Story: they come after The Romans, coincide with The Vikings, and abruptly transform into The Normans at Hastings in 1066. Peopled with colourful characters, it is an exciting, murky part of the story.

Perhaps it was inevitable that the trans-Atlantic house of “Anglo-Saxon studies” cannot stand. Americans laugh at “it’s chewsday, innit”, and, in a similarly imperious vein, they judge us when we use language which, though anodyne to us, seems “problematic” to them.

A deeply unfortunate state of affairs, and one, for reasons of background and a somewhat eccentric education, I only recently became aware of.

On the use of the term among 19th-century scientific racists, whose definition was and should still be regarded as a secondary or even tertiary usage:

It is doubtless true that “Anglo-Saxon” abounds in the lexicon of nineteenth-century scientific racism, and it seems that these resonances reverberate more in North America than here. It is not true, however, that this is the only value-laden use of the term, or that “whiteness” is the only political meaning that its users have historically wished to conjure up. Again, such “misuses” of the term are by the bye, and historians should be permitted to use it in their correct way regardless. But although terms such as “Anglo-Saxons” have been invoked in support of this or that agenda, it is worth pointing out that this has not been the sole preserve of racists and bigots.

Further, on the fact that, despite the prevalence of the term WASP and the abuses of scientific racism, the modern use of Anglo-Saxon still mostly reflects its technical meaning:

Like plenty of terms which have a specialist definition, “Anglo-Saxon” has been deployed over the centuries to convey all manner of different things. Since none of this is inherent to it, it would be perverse for historians to cede ground altogether to any of these disparate groups. Indeed, Anglo-Saxonists should feel fortunate that the specialist sense is the dominant one, at least in British English. They are luckier in this respect than their colleagues who study the Goths or the Vandals.

A great line with which to end that paragraph. I’ve always taken great pains, when teaching late antiquity or the Early Middle Ages, to be clear about what Goth and Vandal mean. As one long ago student helpfully put it, Goths are are people group, not “a phase.”

In Rubinstein’s conclusion, he returns from the sound arguments in favor of keeping and using the term to point out that, in this contest, these scholars are not actually engaged in scholarship: “[Rambaran-Olm] and Wade’s arguments are the stuff not of academic history but political activism. And for all the veneer of scholarship, it seems to me that they know this and are proud of it.” Very clearly, if you have ever read their stuff. And, the conclusion of the whole matter: “The moral of the story is this. Don’t let American idiosyncrasies disrupt sound history. Don’t let scholarship give way to activism.”

Hear hear.

An excellent essay, much more detailed and elegantly put together than my own post about it last year, and worth taking the time to check out. I encourage y’all to read the whole thing at The Critic here.