Great literature is popular literature

/…but not necessarily vice versa.

Two items that got my attention this week and continue some literary themes I’ve thought a lot about over the years (eg here, here, and especially here):

First, a writer at Front Porch Republic bookends his review of Alan Jacobs’s new book Paradise Lost: A Biography with an interesting story. Here’s the beginning of the review:

As I drove into a hotel parking garage one afternoon, I mentioned to the attendant that I had come for a conference on John Milton. “Milton?” he replied. “Wasn’t he the one who had Satan say it’s better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven?” Yes, I said, that’s the guy!

and the conclusion:

Jacobs ends the book by asking whether Paradise Lost has any future outside of academic scholarship. He suggests that yes, it might. . . . After all, if a parking garage attendant in an American city still knows who Milton is, there is hope that Paradise Lost will continue to find admiring readers in the twenty-first century.

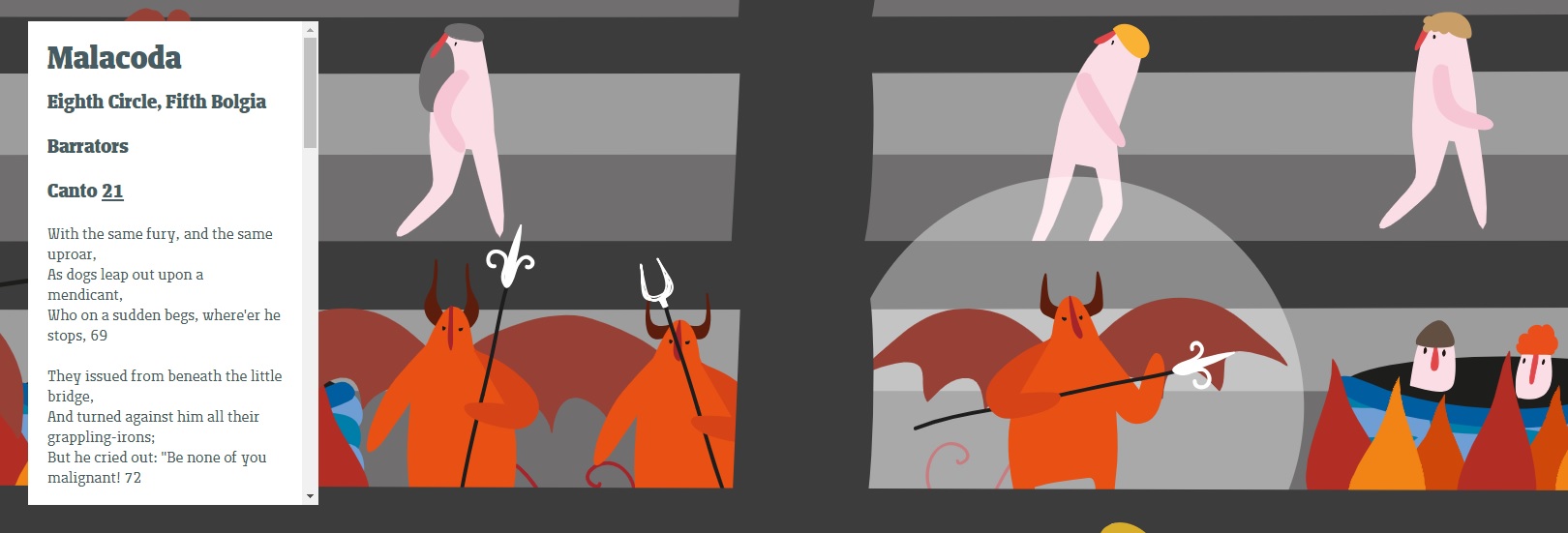

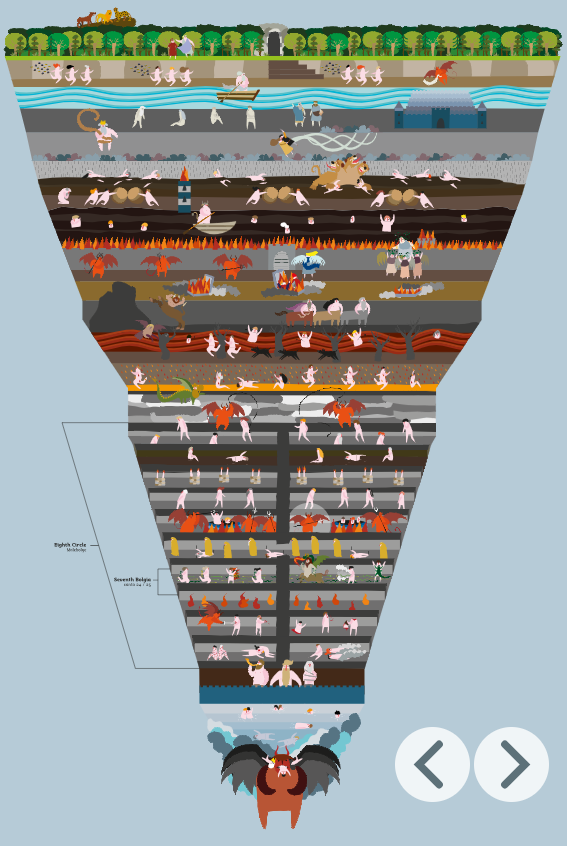

Second, a friend on Instagram sent me this reel of an Italian butcher reciting part of Inferno in his shop. As I noted on Instagram, hearing a native recite Dante really brings out the rhythm of Dante’s verse and especially the rhyme of terza rima in a way I seldom get picking through a bilingual edition. But what I most appreciated was his exuberant enthusiasm for Dante and the way he brought that into his shop. Here’s a man who has passages of the Comedy memorized and can recite them at length for their own sake, not because he’s a tweedy professorial type or so that he can dissect and deconstruct them.

This brought to mind a story about Dante himself related by 14th-century Florentine writer Franco Sacchetti. One day Dante overheard a blacksmith singing some of Dante’s poetry but garbling the words, “clipping here and adding there,” which “seemed to Dante to be doing him a very great injury.” Dante entered the smith’s shop and started hurling his tools into the street. When the smith protested, they had this exchange:

“What the devil are you doing? Are ye mad?”

Dante asked him: “What art thou doing?”

“I am doing my own business,” answered the smith; “and ye are spoiling my tools, throwing them into the street.”

Said Dante: “If thou desirest that I should not spoil thy things, do not thou spoil mine.”

“Thou art singing out of my book,” Dante explains later, “and art not singing it as I wrote it; I have no other trade but this, and thou art spoiling it for me.” Again—a writer’s words matter.

But that’s not my point here. What struck me in both stories were the humble—a butcher, a parking lot attendant—knowing their epic poetry (albeit imperfectly in the case of the smith, but who wouldn’t prefer a world in which you could walk downtown and hear tradesmen and shopkeepers talking about great literature, even if they make mistakes quoting it?). And they didn’t just know this poetry—it mattered to them. In case we needed any further proof, great literature really is for everyone and always has been.

By the way, the butcher is eighth-generation butcher Dario Cecchini. Here’s his shop and one of his restaurants, which specializes in fantastic-looking steaks. If and when I ever visit Florence again, this is on my to-do list. And he’s reciting lines from the beginning of Canto V of Inferno.