The Vikings

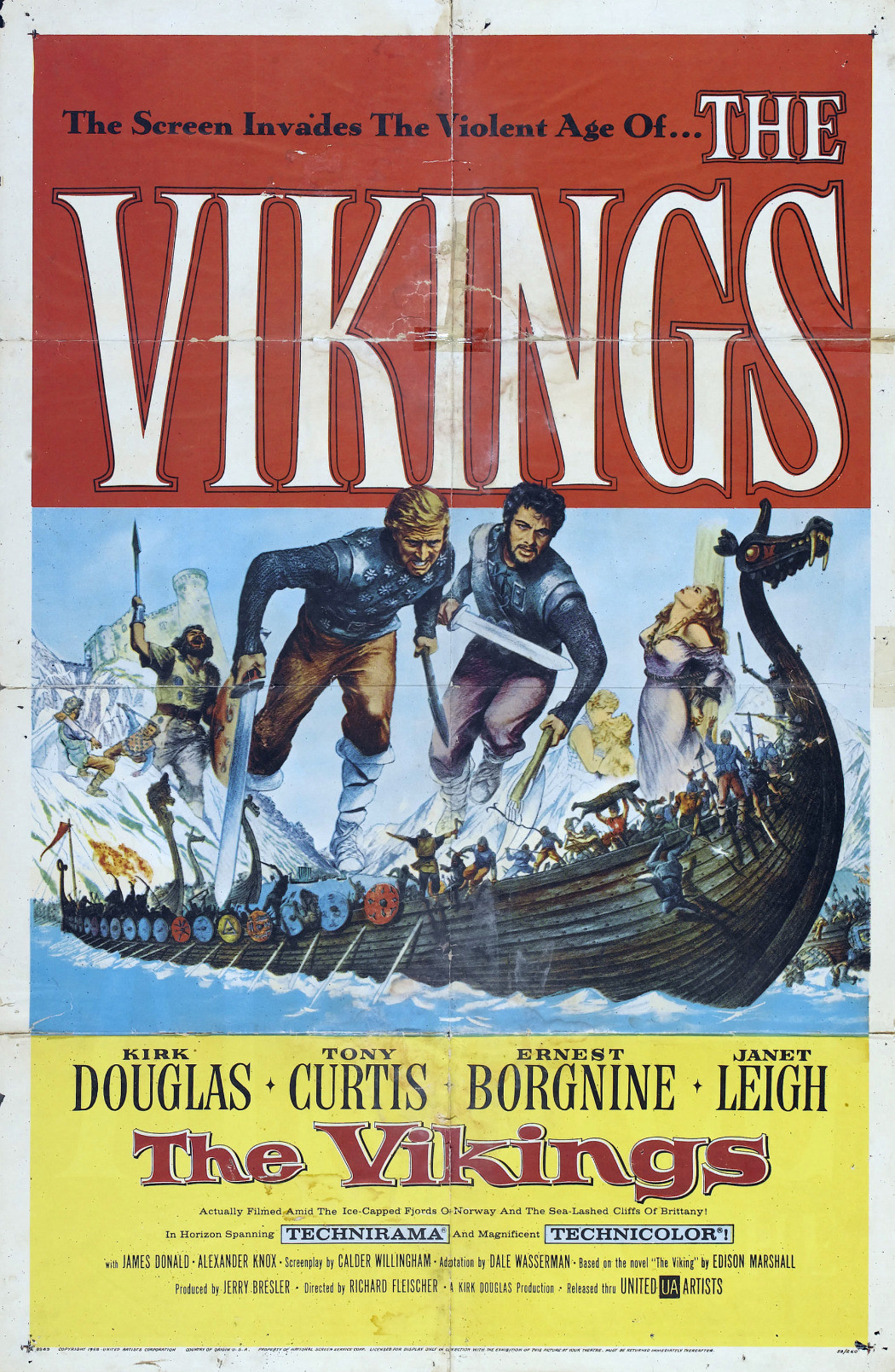

/This week, Historical Movie Monday is pinin’ for the fjords. The film is The Vikings, a 1958 bigscreen epic starring Kirk Douglas, Ernest Borgnine, Tony Curtis, and Janet Leigh.

“I drink to your safe return in English ale. I wish that it were English blood!”

The history

AD 793—like 476, 1066, or 1914—is one of European history's ineradicable points of periodization. Historians debate how important the date is, point to this or that precedent that proves its relative unimportance as one part of a long process, while opponents note how much demonstrably changed after it, and little by little its importance is further cemented. In this case, the year marks the traditional beginning of “the Viking Age.”

While western, Christian Europe—the world of Charlemagne—had prior contact with heathen Scandinavia through trade and travel, 793 is the year raiders attacked the undefended monastery of St. Cuthbert at Lindisfarne on the northern English coast. In a lightning strike from the sea, a small band of Norse raiders surprised, assaulted, plundered, and escaped from the monastery with a huge haul of valuables—including especially human property.

While there are arguably slightly earlier Viking attacks, the raid on Lindisfarne, with its indiscriminate violence, shocked Christendom. The great English scholar Alcuin of York, in a contemporary letter, described how “the pagans have desecrated God's sanctuary, shed the blood of saints around the altar, laid waste the house of our hope and trampled the bodies of the saints like dung in the street.”

Despite prehistorical ties of ancestry, culture, and custom, by 793 the Norse were utterly alien to their victims in Christendom. They were still polytheists who honored heathen gods like Oðinn, Þorr, and the grotesquely endowed Freyr, sometimes with gruesome human sacrifice reenacting Oðinn’s sacrifice of himself to himself, enthusiastically practiced slavery and concubinage, and recognized no limits or boundaries to their aggression. Might made right, a point made abundantly clear in the legends and myths they told about themselves. Heroes like Volsung, Sigurð, and Ragnar Loðbrok took what they could, where they could, showed no mercy—not even to their own children if they proved weak—and all died violent deaths.

Over the 250 years after Lindisfarne, raiders from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden—the “Northmen”—repeatedly attacked along the entire coastline of western Europe and struck deep into modern-day Russia along the Volga and the Don, all the way to the Black Sea, where they were hired as mercenary bodyguards to the Roman emperor in Constantinople. Within a century of Lindisfarne they had reached Iceland, and by the year 1000 had landed in a region they called Vinland before cutting their losses in the face of repeated attacks by the native inhabitants, frightening dark-eyed people they called the skrælings—the Native Americans of northwest Canada.

Due to their proximity to Scandinavia—just a few days’ sailing across the North Sea—the British Isles were the most frequently attacked of the Vikings’ targets. Ireland’s first city, Dublin, was founded as a trading post by Vikings, and of the numerous small Anglo-Saxon kingdoms dividing Britain in 793, all but one, Wessex, fell to Viking attack and settlement, and Wessex only survived thanks to the vision of king Alfred the Great and a complete reordering of its society to defend itself against the invaders.

But like their ancient cousins who had overwhelmed the Roman Empire, the Norse were gradually absorbed from underneath by their victims. One of the most successful Viking warlords, Hrolf (Latinized as Rollo), successfully maneuvered the king of France into offering him a duchy that became known as Normandy. By the time his descendent, William the Conqueror, invaded England, the Norse influence on Normandy remained only in placenames and the big, rugged physiques of its nobility.

Christianization is directly related to the petering out of the Viking Age: whatever the motivations of Norse lords for their conversions, as Christianity took root, the random violence and pragmatic theft dwindled, and Scandinavia began to look more and more like France, Germany, and England—three regions the Vikings, a seemingly existential threat, had once challenged and changed, only to be changed in turn.

The film

Kirk Douglas produced and starred in The Vikings, which came out in 1958. He had done the same for Paths of Glory the year before and would do so again for Spartacus two years later. Like those two films, The Vikings was based on a novel and was packed to the gills with action. Like those two films, Douglas reserved the juiciest part for himself. And like those two films, he excelled in it. One might call these films “vanity projects” if they weren’t so good.

But of these three, The Vikings is probably the film most about the action for its own sake. It doesn’t have the cerebral, meditative quality of the Kubrick-directed Paths of Glory or the ideological passion of Spartacus. But what The Vikings does well, it does very well indeed.

Ernest Borgnine as Ragnar, Janet Leigh as Morgana, and Kirk Douglas as Einar in The Vikings

The film tells a convoluted story worthy, if not quite up to the standard, of Shakespeare. After a brief prologue with wonderful titles based on the Bayeux Tapestry (and narration by Orson Welles), we meet the rampaging Ragnar (Ernest Borgnine), who, within ten seconds of his introduction, kills an English king and—it is heavily implied—rapes the freshly widowed queen. We then see her at the coronation of her late husband's brother Aella as king of Northumbria, a petty tyrant played with arch, greedy effeminacy by Frank Thring (Ben-Hur’s Pontius Pilate). During the ceremony, the queen reveals to a priest that she is pregnant with Ragnar’s child. She hides this fact and, when the child is born, ships him off to a continental monastery for his own safety.

Years later, Aella, perched in his magnificent castle (about which more below), is consumed with defeating the Viking menace, embodied in the still vigorous Ragnar and his son Einar (Douglas). We meet them through Egbert (James Donald, The Bridge on the River Kwai’s Major Clipton) after Aella rather pointedly asks why it is that Egbert’s lands never get raided by the Vikings. Egbert, it turns out, is a traitor, who has sold out his lord and the rest of the kingdom for peace with the Vikings. He escapes to Norway and arrives at Ragnar's home in the first of several stunning sequences of longships sailing into the fjords.

James Donald gives a perfectly awkward fish-out-of-water performance as Egbert when he arrives in Norway, where he settles in with the Vikings and gives the viewer a window into their world. Ragnar spends the time between his raids on Britain partying in his hall, which is created in magnificent and authentic detail, and pestering Einar to be more worthy of him by fighting and plundering more. Einar is vain of his appearance—“He scrapes his face like an Englishman,” Ragnar tells Egbert to explain to us why Douglas didn’t grow a beard for the role—and proud of his conquests and feats, physically and sexually (though always in a 1958-appropriate manner).

Later, while out hawking, Egbert and Einar have a run-in with a slave, Eric. Eric sics his hawk on Einar, who loses an eye in the attack, which is genuinely violent and disturbing. The disfigured Einar is only prevented from murdering Eric on the spot by the old lady who casts runes in Ragnar’s hall. The two will be rivals for the rest of the film.

Also thrown into the mix is Morgana (Janet Leigh, two years before Psycho), a Welsh princess betrothed to the ageing Aella. Ragnar sends a longship to intercept Morgana on her voyage to Aella’s castle and abducts her as a bargaining chip, but Einar—being portrayed by a lusty Kirk Douglas—decides he has to have her and won’t take no as an answer. Eventually, Eric is able to effect an escape from Ragnar with Morgana’s help, and it is to Morgana that he tells his tragic story—he was sold into slavery as a baby, when the ship he was on was captured by the Vikings. No bonus points for guessing whose son he turns out to be.

I rewatched The Vikings last week to prepare for this post and can’t be sure if I’m remembering these story elements and plot devices in the right order—and it doesn’t really matter. The Vikings is high melodrama of the kind Shakespeare delighted to construct, with secret identities revealed, love triangles, tortures and mutilations, violent duels, and a high body count by the end. Ragnar meets his grisly end in a pit full of ravening wolves, there’s a great high-seas chase that ends in a fogbank, and a brutal climactic battle in Aella’s coastal stronghold that ends with a duel to the death. It’s all immensely entertaining.

The film was a major international production, with a budget over $3 million and location shooting in Norway, Brittany, and—of all places—Yugoslavia. Douglas hired Richard Fleischer, with whom he had previously worked on Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, as the director, and Fleischer’s work here is excellent. The scenery, especially the sequences filmed in the Norwegian fjords, is stunning, and the sets are great. The film’s score, by Mario Nascimbene, is rousingly bombastic even if the main theme gets a bit repetitive after a while.

Tony Curtis's gams, front and center for an unfortunate amount of screentime

The performances are good, not great, but again, they’re not really the point. Tony Curtis seems miscast for the first two-thirds of the film until he looks sufficiently roughed up and bearded at the end, when he has to be taken seriously as a warrior. Until then, his prettiness—which I think was only ever an asset as The Great Leslie—and the horrible shorts he’s forced to wear just don’t work. Frank Thring is hamming it up, to good effect. Janet Leigh is passable as the beautiful princess.

Where the actors don’t excel, I think the writing is to blame. The story is fun, but the dialogue is often really obvious. Witness that early scene in which Aella is crowned king of Northumbria. As Aella, enthroned, is presented with a ceremonial sword, part of its hilt falls off and the entire court reacts with stunned silence. Egbert steps forward, picks it up, hands it back to the bishop, glances at Aella, and says, “A bad omen.” Okay. Got it.

The two best performances are those of Kirk Douglas—naturally, since the film is basically constructed for him to show off his charisma and physicality—and, surprisingly, Ernest Borgnine, who is fully believable as a bluff, hearty Viking warlord. His final scene before being chucked into the wolfpit, a scene in which he briefly believes he will be killed in a manner that will keep him out of Valhalla, is excellent.

The film as history

Ernest Borgnine as Ragnar in his hall in The VIkings

The Vikings is based on pulp novelist Edison Marshall’s novel The Viking, which is itself loosely based on elements of Ragnars saga Loðbrokar or The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, which describes the life of Ragnar, who married the long-lost daughter of Sigurð the Dragonslayer, and his eventual capture and death in a pit of snakes at the hands of the devious English king Ella. Ella—Ælla in Anglo-Saxon and Aella in the film—is a real person, having ruled Northumbria for a few years in the 860s before dying in battle with the Vikings at York in 867. This is how fuzzy and incomplete our sources for this place and period are.

Ragnar Loðbrok (literally Ragnar Shaggypants) exists at the hazy edges of history and legend; I’m personally inclined to believe him entirely legendary, like Robin Hood, but we can’t really know for certain.

The rest of the story and its character are fiction but, as George MacDonald Fraser writes in his Hollywood History of the World, it is “fiction against a carefully researched historical background, shot wherever possible in the proper locations, and presented with feeling for its subject.” The film “is what a historical epic should be: an excellent film in its own right, and a striking evocation of period.” Fraser also praises

the film’s atmospheric quality: it is the North on film, rough and cold and raw and beautiful to see, the longships gliding in sunlit triumph up magnificent fjords or slipping away into clammy mist, the gangers carousing in the coarse splendour of their hall, the minute detail of costume and weapon and custom, the triskelion shields advancing over dune and promontory.

“The North on film” is exactly right. The great strength of The Vikings is its evocation of a time and place, a different world. It gets the tone exactly right, and the details—the costumes, sets, props, and customs—almost exactly right.

The clothing, weapons, and other bits of material culture are just about right for the era—the mid-9th century—and Ragnar’s hall in all its beer-swilling chaos is great. The production team took special care to recreate the longships, the signature vessel of the Norse, and the many sequences in which they appear take full advantage of them.

Seen here: not 9th-century fashion

The Vikings themselves are depicted with respect but not blind admiration. Ragnar is a rapist, probably many times over; Einar would be if he got the chance. They like to have a good time and they’re incredibly violent. Neither of these traits is muted or blunted. Viking religion also gets a good depiction, I think, with the myths—the thing most modern people focus on—taking a backseat to ritual, custom, sacrifice, and divination. I struggle to get students to understand that extinct religions were more—much, much more—than the neatly catalogued mythologies they get from Edith Hamilton, Neil Gaiman, or Rick Riordan. The Vikings understands this and enacts its drama accordingly.

Of course the film isn’t perfect, historically speaking. While the combat is mostly good, the realistic shield-wall (skjaldborg) fighting gives way to an Errol Flynn-style mano-a-mano sword-on-sword fight, something that just didn't happen in that era and with those weapons. The Anglo-Saxons also never built stone castles, making the entire showdown at Aella’s fortress (actually a 13th-century castle in France) an impossibility. It’s unclear whether—or, if so, how—runes were used for divination, and the handfuls of Viking funerals for which we have evidence, including the famous Rus funeral witnessed by Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan, didn’t happen like the one in this film, which is singlehandedly responsible for the way Viking funerals are usually imagined now. And, perhaps most obviously, in the dead giveaway of all historical films made in the 1950s, 9th century women didn’t wear those pointy underwire bras.

But despite some non-fatal shortcomings The Vikings is a fun historical adventure, an engaging swashbuckler with authentic Viking trappings, and succeeds better than any other film I’ve seen at—to borrow Fraser’s words—evoking an atmosphere of what C.S. Lewis called Northerness: “like a voice from distant regions . . . something never to be described (except that it is cold, spacious, severe, pale, and remote).”

More if you’re interested

Jackson Crawford, whom I've mentioned here before, is a specialist in Old Norse language, literature, and culture. He published a new translation of the Saga of the Volsungs with the Saga of Ragnar Loðbrok last year. It’s excellent. Check it out if you want a literary immersion course in the world of the Vikings and of Ragnar Loðbrok specifically.

Among the many, many books on Norse history and culture that I recommend are A History of the Vikings, by Gwyn Jones; The Age of the Vikings, by Anders Winroth, who gives a charming and informative one-hour talk on this book here; The Vikings, by Robert Ferguson; The Vikings, by Else Roesdahl, now in a third English edition; and Viking Age Iceland, by Jesse Byock.

And I always recommend going to the earliest sources we have, in this case The Sagas of Icelanders, a great selection of Icelandic sagas, oral stories passed down from the Viking Age that dramatically depict life in that violent era; and, for the opposite side, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which can be just as dramatic with its spare, dire record of Viking attack year after year.

Next week

Medieval March will continue! Thanks for reading.