Remembering my granddad, 21 years on

/My maternal grandfather, JL McKay, died 21 years ago this evening. Few people have taught me or helped me as much, and it astonishes me that I have lived more than twice as long without as with him.

He was a plumber and electrician, good at what he did, and worked with his kids. (He called his business J&L Plumbing & Electric—I can still see it stenciled on the sides of his work ladders—but the initials weren’t just for himself: the J was JL McKay, the L was my aunt Leah, who worked with him for years.) He was a Rabun County native, the second of eight kids born to Percy and Ruby McKay; served in the US Air Force military police in Korea (I remember him telling me about the flash of artillery barrages on the other side of the mountains at night); played basketball for Lakemont High School (long defunct) and was an ardent Braves fan (from at least their Milwaukee days, maybe even since Boston); drove only Fords; subscribed to National Geographic for decades; enjoyed “Jeopardy!,” “Wheel of Fortune,” and “M.A.S.H”; smoked Winstons, which he gave up after surgery in the early 90s (“If I’d known it was going to be my last one,” he said of the cigarette he had before surgery, “I’d have enjoyed it more”); loved fishing and organizing the huge family camping trips to Tugalo, where he’d oversee the camp kitchen and help catch scores of catfish; and was at our small, independent Baptist church for every service.

But the most important thing in his life was clearly his family. After he got back from Korea he married my grandmother, Jewell Dills, raised three kids, and lived to see seven grandchildren. He was always around—I took it for granted that everyone could see their grandparents (both sets) as often as I did. Stories of long, arduous car trips to see grandparents once or twice a year made no sense to me.

In a more important sense, he was not just always around but always there—always there for you, not just his family but for anyone he knew. He was one of the most charitable people I knew, and for all the years since he died I’ve heard stories from people of the favors, kind turns, and simple acts of generosity he performed.

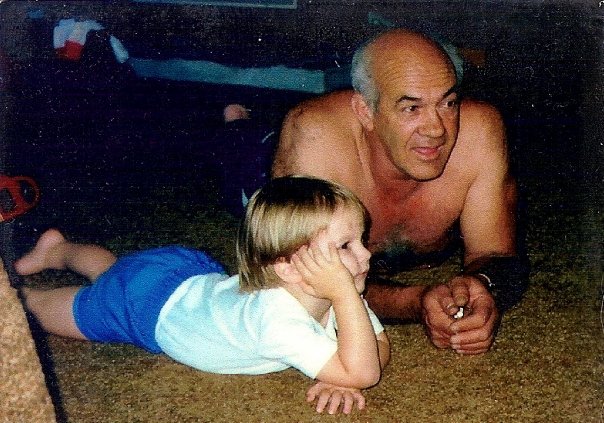

My granddad and I watching TV sometime in the late 1980s

I wrote a year ago, on this same anniversary, about pietas—a mature respect and gratitude to our forefathers. Since then I finished revising and published Griswoldville. That novel is a war story, certainly, but it’s a love letter to a place—Georgia—and especially to a kind of person, the kind of man my granddad was: skilled, hardworking, polite but self-respecting, tough but tender, opinionated but gracious, a steward of the things God gave him, and above all family-oriented. Georgie Wax’s relationship with his grandfather, Fate (a diminutive of Lafayette, my granddad’s middle name) is very much the relationship of me with my grandfathers. I dedicated the book to both of them, my own small act of grateful pietas.

In memory of JL McKay, gone these 21 years, I include a brief episode from Griswoldville. While this novel should only be regarded as fiction, this incident in particular I drew from something my grandfather and I actually did once.

He had an oaken gun cabinet that seemed, when I was a kid, five stories tall, with three or four shotguns, a .22 magnum varmint gun, and a lever-action .30-30 that stretched away up into the darkness at the top of the cabinet. I remember squinting through the glass door many times to try to discern the ends of the barrels up there. One day he took one of his shotguns down and we trooped up the hill behind the house into the junkyard were he kept mountains of spare piping, wire, and fixtures. He wanted to show me the basics of how to hunt squirrels. We spotted and shot one but the shotgun tore up the meat too much to be edible. Then he showed me what Fate teaches 11-year old Georgie in this passage.

* * * * *

We brought in three bales of cotton on our farm and two and a quarter on my uncle Quin’s, all of which we sold through the cotton factor that visited the MacBean place every fall. We picked and bagged the terrible bolls until our hands hung so bloody raw and abraded we could not reach into our pockets without agony. A blind gypsy could have read our fortunes sniffing the blood caked in our lifelines. A team of Negroes arrived and loaded the bales onto wagons and carted them off to the railhead in Athens, from whence they would ride to Savannah. I found out later that the price was a great disappointment, as the Confederate government in Richmond had ended exports of cotton in an vain effort to bring some European power into the war, and we were not to plant it again until years afterward. In between there would be much worry over cash, even for farmers. We brought in good crops of oats and corn and fairly stuffed our hogs—who were already nigh spherical with acorn mast—with the latter. Slaughter approached, and we needed the pork. With harvest ended and hog-killing time not quite upon us, and the frosts arriving and our breath coming like broken glass when we ran or worked outside, my grandfather oiled his rifle and shotgun and took me hunting.

I had watched him hunt before, and even taken potshots at squirrels and raccoons, but now he let me carry the guns and taught me in earnest how to bring down small game.

“Your father left you in charge,” he said, “and a man ought to be ready to provide, any time. I’m just here to help.”

He taught me to clean and skin the game on my own and—when my fifth or sixth squirrel dropped out of the trees too torn up to be good for food—a trick of his that I never forgot.

We had just left the porch one morning and by accident flushed some squirrels from my mother’s garden patch, where they had been foraging among the stalks and remains of what we had missed in the picking. They scampered to the fields, up the side of the house, behind the muleshed, and into the shade tree.

My grandfather produced his powder and measured a charge for the rifle. “Let’s get started with these rats here.”

I grounded the shotgun and brought out my powder and pellets.

“Not this time, Georgie. I want to show you something.”

He loaded without looking at the rifle. He regarded the two or three plump squirrels watching us upside down from the shade tree. The tree was a great white oak, older even than the state, five feet wide at the base and better than seventy feet tall. In the high summer we watched the yard like a sundial with the tree as its gnomon.

My grandfather brought the rifle to half-cock and fastened a percussion cap to the nipple. He nodded toward the tree.

“See that fat one there, bout halfway up?” One of the squirrels sat, contented with his distance and sanctuary, dead center in the thickest part of the trunk, about twenty feet up.

“Yes, sir.”

“Watch, now. My granddaddy taught me this.”

He thumbed the hammer to full cock and raised and sighted. The squirrel moved its head minutely, taking in this new intelligence. I heard my grandfather softly breathe out and he fired. The ball struck the trunk of the oak just above the fat squirrel’s head with a sound like a hammer on a loose plank—a miss. And the squirrel flopped backward to the ground anyway.

My grandfather and I stood wreathed in the sulphurous reek of the rifle. The surviving squirrels skittered up and down the tree; a distant dog commenced to barking. I looked at the lifeless squirrel in the yard and up at my grandfather, who grounded the rifle and grinned wide, pressing his tongue against the back of his teeth and chuckling.

At last, he said, “Whew!”

“How—”

My mother burst out of the house, black hair loose, apron in hand.

“God sakes, Daddy!”

“Fixing to rid your okra patch of squirrels, Mary,” he said.

I pointed, awed. “He killed it without even shooting it!”

“If you possess such power why don’t you forebear to shoot at all?”

My grandfather retrieved the squirrel and handed it to me.

“Georgie’s got to learn. He needs a teacher.”

My mother shook her head and strode back into the house. From inside, I heard her declaim to one of my younger brothers about being startled half to death. I laughed and looked at the squirrel. My grandfather grounded the rifle and set to measuring out his powder again.

I turned the squirrel over in my hands. It was still warm and completely unmarked. I looked at its yellow maloccluded teeth and felt an uncanny prickle of fear—I had seen boys with fingers bitten clean through by squirrels and did not want this creature awaking in a fright in my still-tender cotton-raw hands.

“You know what concussion is, Georgie?”

I looked at my grandfather. He stowed the ramrod and waited. “No, sir.”

He balled a fist and struck the open palm of his other hand. “That’s concussion. Shock—the force of smiting something. It’s the concussion, of a kind, that knocks a man down when you strike him. The concussion of your fist on his skull. Now, you knock a man hard enough, the concussion on his skull knocks his brains into his skull. You can do a most powerful lot of harm to a man, you strike him hard enough. You understand?”

“Yes, sir. That’s why you don’t want us fighting? That’s why you say men don’t fight?”

He chuckled. “Naw, men don’t fight each other cause that’s the worse way to go about settling things. But we can talk on that later. Now, what I said about concussing a man’s brains? This bullet—” and he produced one, a .32 caliber lead ball, “—when it strikes a thing, concusses everything around it. You feel a cannonball strike close by, you feel the earth shake. You feel a bullet pass close by your face, you feel it clap the air by your cheek. You hit a tree trunk like that close enough to a squirrel’s skull—not too close, not too far—the concussion knocks its brains and kills it dead just like that. Don’t tear up the meat, don’t hurt the squirrel.”

I marveled over the squirrel. He took it and handed me the rifle. It seemed suddenly like a more powerful instrument than a mere squirrel gun. My grandfather had ennobled it.

“Your turn, Georgie.”

* * * * *

You can read more from Griswoldville here. I hope y’all enjoyed this passage, and will let the memory of my granddad—or men like him—lift and guide you today. We need more people like him.