2021 in movies

/Dang, the pickings are slim, aren’t they? 2021 was an even worse year for movies than 2020 if, like me, you’re completely burned out on Marvel, aren’t going to see a movie simply because it has an ideologically or politically correct message, and don’t pay for any subscription streaming services.

Nevertheless, I did get out to theatres a number of times and also caught some good films on home video afterward. But that was not nearly as often as I would have liked. So, rather than a top five, any movie I liked made it into the post this year.

Dune

Oscar isaac as Duke Leto Atreides in Dune

Certainly the best film I saw this year, Dune is an excellent movie in its own right as well as a skilled and well-crafted adaptation of Frank Herbert’s elephantine sci-fi novel. The cast, design, cinematography, special effects, music—all are excellent, and all contribute to an involving, exciting film of operatic scale and epic scope. I look forward to Part II.

I say all of this as someone who originally did not have much interest in either the book or the movie, as I explain in my full, much more detailed review, which you can read here.

No Time to Die

Rami Malek as Lyutsifer Safin in No Time to Die

Dune was certainly the best film as a film that I saw this year, but I think the one I enjoyed the most was Daniel Craig’s final outing as James Bond, No Time to Die.

The longest and heaviest of the series so far, No Time to Die pits Bond against Lyutsifer Safin (Rami Malek), an eerie supervillain with an interest in virology, nanotechnology, and poison who has plans both for his own old enemies—not only Bond, but Quantum and SPECTRE—and for the world. Safin’s plot places Bond’s last serious girlfriend, Madeleine Swann (Lea Seydoux) in harm’s way, and Bond is called out of retirement for a mission he may not be up to, either physically or emotionally.

No Time to Die, as I wrote after I saw it, “is a whole lot of movie.” It’s overlong, overcomplicated, and needlessly develops continuities with the previous Craig films, especially Spectre, and I feel like the impact of its big action finale and especially its surprising ending were diminished by some of these story choices. But it also features seriously good action, a good villain, great locations, an intriguing and all-too-real premise, and Craig in his best form as Bond since Skyfall.

A solid ending to Craig’s tenure. I rank it in the middle of the pack, below Skyfall and Casino Royale and above Spectre and Quantum of Solace. You can read my full review here.

The King’s Man

The Duke of Oxford (Ralph Fiennes) confronts Rasputin (Rhys Ifans) in The King’s Man

I saw and really enjoyed Kingsman: The Secret Service when it came out in 2015, but did not see its sequel. This was a franchise I’d enjoy if I ran across it—or whenever the mood to watch the first film’s “Freebird” sequence struck. Then, lo and behold, a trailer appeared for The King’s Man, a prequel set during World War I and starring Ralph Fiennes and looking like a jazzier, more masculine version of the Western Front hijinks in Wonder Woman. I was sold.

I’m glad to say I saw The King’s Man earlier this week, and it’s a hoot—a mostly light-hearted historical fantasy romp through some of the big names and a whole lot of the fashions and hardware of the 1910s. This is Pirates of the Caribbean for World War I.

The King’s Man centers on the Duke of Oxford (Fiennes) and his son Conrad (Harris Dickinson). Following a prologue set in a Boer War concentration camp (the friend who saw it with me, who lived in South Africa for some years, remarked: “Didn’t see this coming”), in which Oxford and son lose their wife and mother to Boer snipers, we catch up with them in 1914 as tensions escalate throughout Europe. Oxford is a dedicated pacifist who refuses to allow Conrad to enlist; Conrad bridles at his father’s principles and the damage they do to their public reputation. But Oxford is adept at pulling strings and using connections, especially Lord Kitchener (Charles Dance), and this aptitude and the skills of some of his household staff (Djimon Hounsou and Gemma Arterton) create not only unofficial capacities in which Conrad can serve, but creates a network of intelligence and special operations that evolves, by the end of the war, into the Kingsman organization we know from the other films.

This organization becomes important as one of the only bulwarks against a mysterious group of international terrorists who meet, Blofeld and SPECTRE-style, in a faraway hideout to plot against the major powers, and the Kingsman’s contests with the mystery archvillain’s agents take up much of the runtime. Along the way there are some outlandish operations, a lot of Bond-style globetrotting, a ton of cameos from real historical figures from the era, and even a genuinely surprising tragedy that sets the finale in motion.

This movie is all over the place, with wink-wink broad comedy—as in a sequence in which our heroes, misled into thinking that Grigori Rasputin (Rhys Ifans) is homosexual, attempt to seduce him, a sequence that turns into a bizarre healing ritual for Oxford’s maimed leg and finally a swordfight/Cossack dance set to the 1812 Overture—interspersed with dark, realistic war scenes. A hand-to-hand fight in no-man’s-land between two groups of trench raider is particularly harrowing. There’s potential for mood whiplash here, but you know what? It worked for me. It was so outlandish, so outrageous, and so daring that I was glad to go along for the ride. I do not say this often, so take note—check your brain at the door. It’s worth it.

The King’s Man offers an additional layer of fun for anyone versed in World War I history. Though the history here is grossly oversimplified—you’d think, based on this, that the only countries involved in the war were Britain, Germany, and Russia—a ton of real events are worked into the fantastical conspiracy framework of the movie, and numerous historical figures appear, including Lord Kitchener, Rasputin, Erik Jan Hanussen, Mata Hari, Gavrilo Princip and Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Vladimir Lenin, Woodrow Wilson (seduced and blackmailed by Mata Hari, making the retrieval and destruction of a Woodrow Wilson sex tape an important plot point), and—in my favorite bit of casting in a long time—Tom Hollander as King George V and Kaiser Wilhelm II and Tsar Nicholas II. None of it is very accurate, and it halfheartedly tries to work in an incoherent pacifist message, but it’s a hoot, and I and the buddy I watched it with enjoyed ourselves immensely.

Check out The King’s Man if you’re up for an outlandish historical action-adventure with a dash of the fantastical and a Monty Python-style grasp of history.

The Last Duel

Jean de Carrouges (Matt Damon) and his wife Marguerite (Jodie Comer) in The Last Duel

I left my copy of the book this film is based on in my office over Christmas break, so I can’t attest to the film’s total accuracy (especially since I’m an Early Medieval guy, not a Hundred Years’ War guy), but I was really taken with The Last Duel.

Briefly, The Last Duel begins with the last judicial duel or trial by combat ever fought in France and backtracks to tell us how the two knights involved, Jean de Carrouges (Matt Damon) and Jacques Le Gris (Adam Driver), got to this point. And it tells us three times—first from Jean de Carrouges’s simple, noble perspective as a loyal but often aggrieved retainer; second from Jacques Le Gris’s corrupt, self-aggrandizing, and considerably more carnal perspective; and finally from the perspective of Marguerite de Carrouges, Jean’s wife. Marguerite claimed to have been raped by Jacques, and as Jean pressed his suit and Jacques continued to deny the rape had ever occurred—variously stating that it either never happened or was a consensual affair—Jean asked for a trial by combat, a survival of ancient Frankish custom that put the judging of who was telling the truth in the hands of God. Survive, and you were exonerated. The stakes are not only high for the two knights involved, one of whom, according to the terms of the custom, must die for judgment to be rendered, but for Marguerite, who will be executed as a perjurer should Jean be killed.

I’ve made no secret of my distrust of Ridley Scott when it comes to handling historical material, and given the way the film was marketed and talked about—as if it were some kind of medieval #MeToo manifesto or damning indictment of medieval Christian patriarchy or whatever the bugbear of the day is—I was pleasantly surprised with how good The Last Duel was. The film, which is structured in three “chapters,” one for each major party’s perspective, presents each chapter straightforwardly, dropping the viewer into the complicated world these characters inhabit and letting us experience all of that well before the incident that leads to the dueling ground. Inheritance and dowry, the pressures of lordship and producing an heir, the difficulty of managing estates and fielding armies, the roles of law and custom, interfamily rivalries and dissension even within families, shifting alliances and damaged reputations—all factor in and influence the proceedings. It’s a remarkably evenhanded treatment of a complex alien world for a filmmaker who has previously had no problem manipulating the past to make it either more familiar or more useful for his purposes. I credit the writing, which Damon and Affleck had a hand in and which is better than some of Scott’s other historical films.

The Last Duel is, unsurprisingly given Scott’s strengths, a great-looking film. I have quibbles about costuming, combat, the way some of the characters talk, some of the inevitable Dark Ages stereotypes, and even breeds of dogs (a Boston terrier in the 14th century? really?), but overall the film is visually stunning and has a feeling of tactile reality to it that I wish more historical films could manage.

The performances are also excellent—crucially so, since the three different versions of events we get must have both striking and subtle contrasts. Jodie Comer as Marguerite has earned effusive praise, and while she was very good, I was honestly much more impressed with Damon and especially Driver. Both do a lot of subtle work differentiating their characters across the three versions of events, and do so in a way that doesn’t call attention to itself or require explicit explanation. Jean de Carrouges comes across as a relatively simple, shallow, but driven and honorable man; Jacque Le Gris, even in his own version of the story, as a dissipated but worldly and intelligent striver. The movie doesn’t uncomplicate these characters looking for easy bad guys, which I appreciated.

There are other things I could quibble with. An early line from Jean’s mother, that “There is no right, there is only the power of men” is shockingly un-medieval, and some of the legal talk, especially regarding the startlingly brutal punishments for crimes, is oversimplified and misleading (as is pointed out in this piece at Slate, of all places). But I think the film’s biggest misstep comes with the beginning of Marguerite’s perspective. On the title card for “Chapter III: The Truth According to Marguerite de Carrouges,” as the title fades out only “The Truth” remains for a moment. This choice wrecks a lot of the ambiguity the film has thrived on up to this point, and suggests that we can confidently know what happened to these real people in this real incident. (We can’t.) It also plays into the tired feminist trope of women being the only truth-tellers, especially since, in scenes of Marguerite sorting out her husband’s estates’ finances and managing the household and farms (as if this was somehow exceptional for medieval noblewomen, all of whom had vast domestic authority), it suggests Marguerite is the only intelligent and capable person in a world of brutish warriors. Again, a tired feminist trope.

But that aside, I found myself deeply involved in The Last Duel and admired its careful, largely hands-off storytelling approach. And the duel, when it arrived, proved powerfully cathartic.

The Last Duel is a worthwhile if flawed adaptation of a true story with great attention to the complex social world in which these events took place. It’s grim, especially considering the nature of the crime against Marguerite, which we’re presented in two different versions, and its conclusion is brutal, but it’s a worthwhile historical film of the kind they’re making less and less of.

Luca

Luca and best friend Alberto in Luca

Luca is Pixar at its finest—bright and inventive, with beautiful settings and animation, good music, and a fun story made fresh and meaningful by the characters and their relationships. I also appreciated, as with the next film I’ll talk about, the relatively low stakes. Three friends want to win a race so they can use the cash prize to buy a motor scooter. Refreshing.

Two adolescent boys testing boundaries, visiting parts of town they shouldn’t, making new friends, keeping secrets, and setting themselves magnificent goals—this could be Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn or another number of other literary friends, and Luca draws deep from the well of young male friendship.

While the friendship between young sea monster boys Luca and Alberto forms the core of the movie, alongside a deepening connection between Luca and the vivacious human tomboy Giulia, the relationship that most powerfully spoke to me was that between the homeless, parentless, aimless Alberto and Giulia’s father Massimo. The way the taciturn Massimo senses Alberto’s need for masculine guidance, discipline, and work—that is, for a father—and selflessly moves to meet that need brought to mind the multiple generations of aimless, fatherless boys and men our society produces now and left me wanting to be more like Massimo. It’s a quiet but moving subplot that really deepened the film, and parallels Luca’s own quest for education of the book-learning variety. Both boys end the film having been given tools to meet needs they didn’t even know they had, and both receive these things through relationships.

The voice acting is good and the Italian scenery beautiful—not to mention all the pasta, which is the most delectably animated food since Ratatouille. But most of all it’s pure fun, poignantly evoking the joys of childhood friendship on the terrifying cusp of adulthood and speaking to the need we all have for both peers and parents.

Paw Patrol: The Movie

If you have kids, you don’t need me to name all these characters for you

You know what? I’m thirty-seven years old. I have three kids between the ages of two and six. So yes, I saw this. And I mostly liked it.

Paw Patrol: The Movie takes Ryder and his team of pups away from their usual jurisdiction of Adventure Bay to the much busier, more bustling Adventure City, where the nefarious Mayor Humdinger has just managed to be elected mayor on a technicality. Local pup Liberty calls the Paw Patrol about this emergency (about which more below) and the crew removes to Adventure City where they set up in a Stark Tower-style headquarters and work to ameliorate as much of Humdinger’s chaos as possible. There’s a strong taste of the superhero movie to these proceedings. Perhaps my favorite incident involves Humdinger’s unveiling of a new L-train with loops in it, a bit of infrastructure that goes spectacularly wrong very quickly.

You can probably tell that this is a lightweight movie, and to that I say: Please, sir, can I have some more? The story unfolds at precisely the kid-friendly nonsense level of the TV show—the only thing that matters is that there are emergencies to which the pups can respond with their infinite variety of vehicles. I found it refreshingly low-stakes.

Paw Patrol: The Movie is like a supersized episode of the TV show with a much bigger budget and, therefore, strikingly better animation. The pups in this movie have actual fur, and their environments are much more detailed and vibrant. There are even slow-motion action sequences for added drama, as when Chase, the police dog, risks a dangerous leap for a rescue, which elicited a “Whoa” from my kids.

There were only two flaws—for me, an adult viewer of Paw Patrol: The Movie. The first was the relative sidelining of much of the cast in order to develop a tragic backstory for Chase. We learn that he is hesitant about going to Adventure City because he was abandoned there as a (even younger?) pup. Standard stuff for fleshing out a ninety-minute movie, but part of the charm of the show has always been the variety of the characters. Here, Zuma (something like a Coast Guard dog) and Rocky (who drives a recycling truck but whom I always call a “garbage dog”) are virtually background characters.

The other flaw—again, for me, an adult viewer of Paw Patrol: The Movie—was the new character, Liberty. Liberty is the worst. In her first scene she physically threatens a man for littering, she breaks any rules she doesn’t agree with, and she calls the Paw Patrol—emergency services—because she doesn’t like the outcome of an election. Hmm. She then spends the rest of the movie insinuating herself into the Paw Patrol, claiming to be an “honorary member,” and is rewarded with her own membership and set of vehicles at the end. She’s constantly irritating, and the only redeeming factor is the way Ryder acts weirded out by her. Her sass and entitlement also throw into relief the idealistic way the normal cast are presented on the show: as good-natured and selfless public servants, something I never thought to admire in such a silly children’s entertainment before. Here’s hoping the show leaves Liberty in Adventure City.

If you have kids of the right age, this is a fun, charming, big-budget version of something they’re already sure to enjoy, and I’m happy to recommend it on those grounds.

New to me

Cliff Robertson in 633 Squadron (1964)

With the theatres a waterless wasteland in which the only movement to be seen is the lonely rolling of superhero tumbleweeds, this turned out to be a great year for movies I’ve been meaning to see for a long time. This was especially the case with war movies, as you’ll see below.

The Dam Busters (1955)—A classic of the war movie genre and an excellent dramatization of one of the most daring and dangerous missions of the Second World War. It’s well-acted and produced, featuring lots of great aircraft and aerial photography, and despite the limitations of the 1950s British film industry’s special effects, the miniatures, slow motion, rear projection, and optical effects like animated tracer rounds are still effective. And though the film doesn’t cover every loss on the night of the operation or give attention to civilian casualties as a result of the flooding caused by the raids, it still ends on a reverent downbeat note, a moving acknowledgment of just how much this technically accomplished and ingenious operation cost. An engaging and powerful true story well told.

633 Squadron (1964)—I was interested to check this film out because of its odd connection with The Dam Busters: both were inspirations for Star Wars, something that is blindingly obvious if you watch both films with that in mind. (See here and here.) As it turns out, 633 Squadron, though a fictional story, is by turns a fun and gripping evocation of the daring and skill required of the pilots of the British Mosquito fighter-bomber. Cliff Robertson, as an American volunteer leading the squadron, is very good in an understated role, though West Side Story’s George Chakiris is absurdly miscast as a Norwegian resistance leader—casting made yet more ridiculous in that this obviously Greek man is paired with the blond-haired, blue-eyed Austrian actress Maria Perschy as his sister. Regardless, this film is a good deal of fun, has a lot of excellent aerial photography using both models (not always convincing, but effective enough) and a fleet of real Mosquitos collected for the film. It also has a grim, heavy ending comparable to its much better cousin The Dam Busters.

13 Minutes (2015) and The 12th Man (2017)—Two excellent foreign films set in and around World War II. The first is a German film about Georg Elser, a lone-wolf assassin who attempted to kill Hitler with an elaborately engineered time bomb in the early days of the war. The second is a Norwegian film about the harrowing survival of Jan Baalsrud, the sole survivor of a botched commando raid. Both are true stories, and both are excellent. I watched these during my quarantine back in the spring; you can read my thoughts on both of them here.

Max Manus: Man of War (2008)—An excellent action movie about Norwegian resistance fighter Max Manus, who had extraordinary guts, having volunteered to fight for Finland during the Winter War before undertaking resistance operations against the Nazis. In one incident, Manus was wounded and captured and escaped by flinging himself through a hospital window to the street several stories below. Brings home both the courage and ingenuity of the resistance as well as the cost and, all too often, the futility of these operations.

A Night to Remember (1958)—An unsentimental, well-acted, and well-produced film about the sinking of the Titanic that also manages to be more comprehensive than any other film version. Despite its disadvantages in terms of special effects, I’d recommend A Night to Remember over James Cameron’s bloated, cliched turkey of a movie any day. I was so moved by A Night to Remember when I watched it back in the spring that I made sure to review it; you can read that full review here.

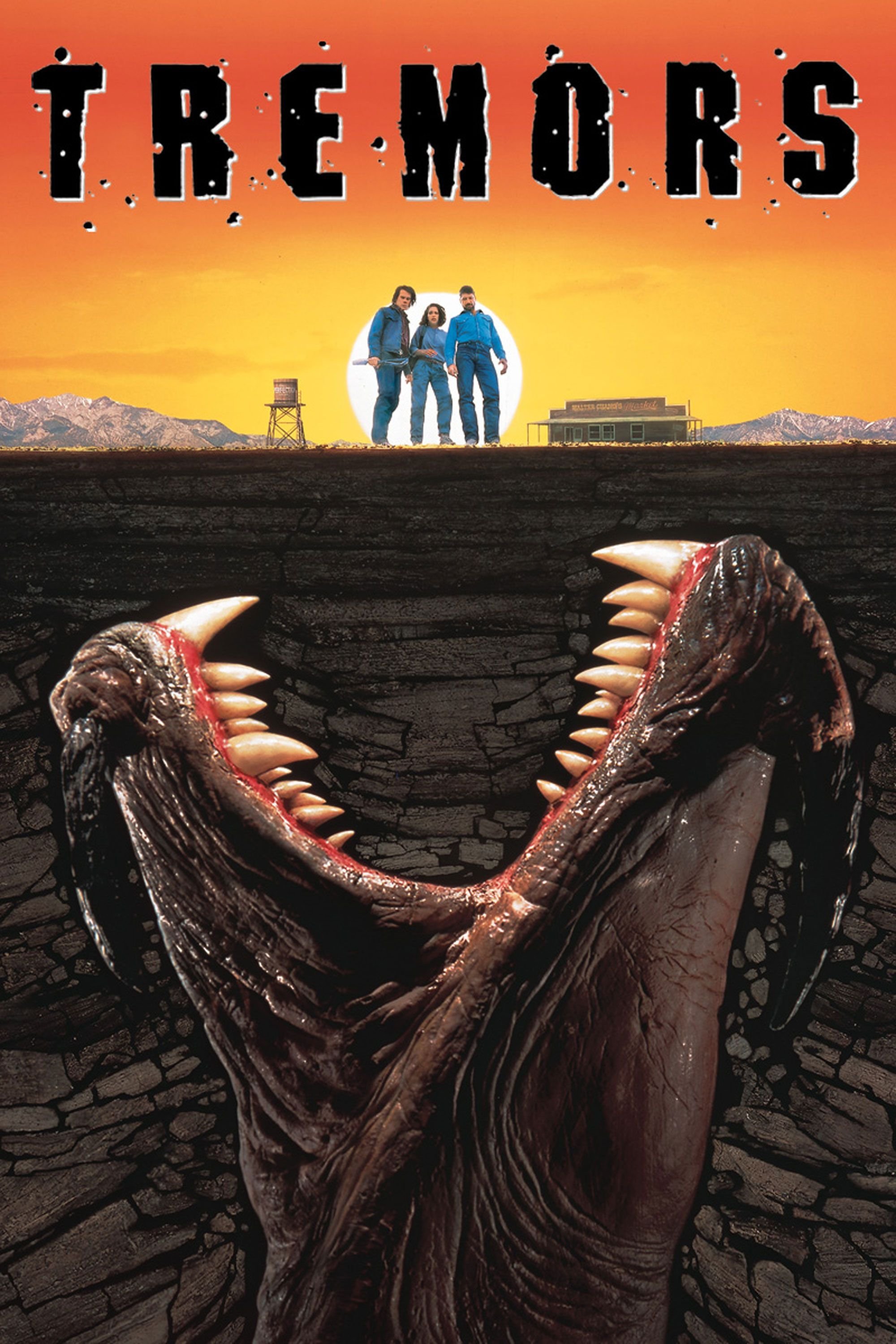

Tremors (1990)—My first memory of Tremors is of one of my cousins telling me—nearly thirty years ago—about a scene in a movie where Reba McEntire runs from a monster into a room full of guns. That made an impression, as did the Jaws-ripoff poster at the video store nextdoor to the BBQ restaurant in Wiley. Long story short, I don’t know why it took me so long to get around to seeing this, but it’s a hoot, and a high-quality hoot—funny, well-written, well-cast, perfectly structured, and perfectly balancing comedy, horror, and action.

Near misses

Tom Hanks as Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd in News of the World

Here are three movies I’m calling “near misses,” because while I liked elements of them, they had enough flaws or I had enough misgivings about them that I couldn’t wholeheartedly enjoy or recommend them.

The Lighthouse—A brilliantly acted, oppressively atmospheric, and beautifully produced movie that is nevertheless too in love with itself for its own good. Part of my quarantine viewing this spring.

The Green Knight—See my remarks on The Lighthouse above. In addition to entirely too much regard for its own artfulness, The Green Knight also fails as an adaptation, as all of the changes made to what is rightly regarded as a masterpiece diminish the story and its themes. Read my full review here.

News of the World—This is my favorite of the three films I’m lumping into this category, and I expect it will grow on me. But while it’s an accomplished movie, beautiful to look at and brilliantly acted by Tom Hanks and the young Helena Zengel, I found that, like The Green Knight, where it deviated from its source material it did so to its story’s detriment. In this case, that was a lot of socially aware posturing of the kind that clearly appeals to director Paul Greengrass—we get a lynching in the first five minutes, eliminating a black character who is an actual character in the novel rather than a literally faceless victim, and later there’s a whole sequence of labor relations drama that feels like something from the 1970s rather than the 1870s—but that distracts from the emotional core of Paulette Jiles’s straightforward but subtle and powerful novel. (Coincidentally, I reviewed and recommended the novel in the very first post on this blog four years ago today.)

What I missed in 2021

Three movies from this year that I wanted to see but, for various reasons, I have not gotten around to yet:

The Little Things—A serial killer mystery from John Lee Hancock, director of The Blind Side, The Founder, and an underrated masterpiece that I seize every opportunity to stump for, The Alamo. Hope to catch this in the new year.

Spider-Man: No Way Home—As much as I’ve criticized the unceasing flood of superhero movies, the only one that caught my interest this year was this third installment in the Marvel-affiliated Tom Holland Spider-Man series. Word from friends and family is that it’s a lot of fun, but I still haven’t seen it and have been content to catch the first two—Homecoming and Far From Home—on video later. That will probably be the case here.

The Tragedy of Macbeth—Joel Coen’s solo project (rumor has it that brother Ethan is done making movies, which I dearly hope isn’t true), an artsy black-and-white adaptation of my favorite of Shakespeare’s plays, apparently got a very limited arthouse release at Christmas but will only be available to us plebs in January. I’m looking forward to it.

What I’m looking forward to in 2022

Though I’ve bemoaned the state of movies and filmmaking a lot, especially this year, I do find there is much to look forward to—and if you look at what I was looking forward to a year ago, you’ll see that at least some of those turned out to be excellent! Hope springs eternal.

The Northman—A Viking Age revenge drama that, to judge from the trailer, takes its historical setting and the alien worldview of its characters more seriously than usual. You can read my reactions to and observations based on the first trailer here.

Munich: The Edge of War—An espionage drama, based on the novel Munich by Robert Harris, set against the backdrop of the 1938 Munich Conference. 1917’s George Mackay plays the lead, with Jeremy Irons as Neville Chamberlain. Disappointed to learn that this will be released by Netflix in the US; hoping for a release on home media somewhere down the line.

Operation Mincemeat—A true story, previously told in the 1956 film The Man Who Never Was, when parts of the operation were still protected secrets, this film is based on the deeply researched and highly readable book by Ben Macintyre and should tell the whole story: how British intelligence mounted an ambitious but morally dubious disinformation campaign by fabricating a false identity for the corpse of a homeless man, planting documents on his person that would lead the Germans to move military resources away from the target of a coming Allied attack, and depositing the body off the coast of Spain where it was sure to be discovered. Great cast including Colin Firth and Matthew Macfadyen (or, as I am already calling them, the dueling Darcys) and Johnny Flynn as Ian Fleming. Another movie that the abominable Netflix has scooped up.

Lightyear—Pixar gives us the movie that inspired the toy line from Toy Story—or something. Looks like it could be delightful.

Death on the Nile—Kenneth Branagh’s Poirot returns in this big-budget, ensemble cast sequel to his Murder on the Orient Express. This film has already been delayed several times; hoping the studio will finally bring it out in the new year.

Top Gun: Maverick—Ditto the above. Just release the thing already.

Mission: Impossible 7—A dependably solid franchise, with excellent action and stunts. Hoping for more in the same tradition.

Downton Abbey: A New Era—Guaranteed date night success.

Conclusion

Looking back at all I’ve written about, maybe 2021 was a better year for movies than I initially gave it credit for. At any rate, I watched a number of worthwhile, entertaining, enjoyable, or thought-provoking films this year, and I hope you’ll check some of these out, too.

Thanks for reading, and best wishes at the movies for 2022!